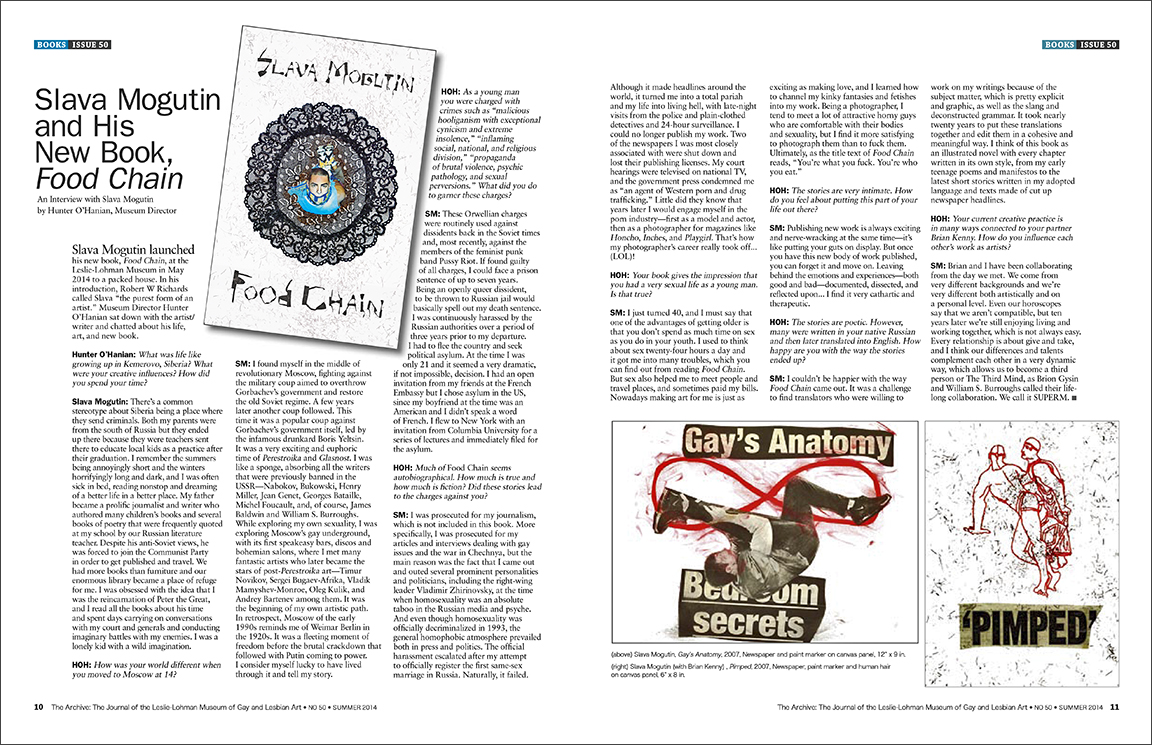

Hunter O'Hanian Interviews Slava Mogutin

HUNTER O'HANIAN: What was life like growing up in Kemerovo, Siberia? What were your creative influences? How did you spend your time?

SLAVA MOGUTIN: There’s a common stereotype about Siberia being a place where they send criminals. Both my parents were from the south of Russia but they ended up there because they were teachers sent there to educate local kids as a practice after their graduation. They fell in love with Siberia and each other and decided to stay. In the summer my father would spend weeks at a time hunting and fishing in the Taiga, and we always had plentiful supplies of dried fish, our favorite snack. I remember the summers being annoyingly short and the winters horrifyingly long and dark, and I was often sick in bed, reading nonstop and dreaming of a better life in a better place. My father became a prolific journalist and writer who authored many children’s books and several books of poetry that were frequently quoted at my school by our Russian literature teacher. Despite his anti-Soviet views, he was forced to join the Communist Party in order to get published and travel freely around the country and as far as Mongolia and Bulgaria. We had more books than furniture and our enormous library became a place of refuge for me. I was obsessed with the idea that I was the reincarnation of Peter the Great and I read all the books about his time and could spend hours and days carrying on conversations with my court and generals and conducting imaginary battles with my enemies. I was a lonely kid with a wild imagination.

HOH: How was your world different when you moved to Moscow at 14?

SM: I found myself in the middle of revolutionary Moscow, fighting against the military coup aimed to overthrow Gorbachev’s government and restore the old Soviet regime. A few years later another coup followed, and I described it in my story The Death of Misha Beautiful. This time it was a popular coup against Gorbachev’s government itself, led by the infamous drunkard Boris Yeltsin. It was a very exciting and euphoric time of Perestroika and Glasnost, and I was like a sponge, absorbing all the books that were previously banned in the USSR—Nabokov, Bukowski, Henry Miller, Jean Genet, Georges Bataille, Michel Foucault, and, of course, James Baldwin and William S. Burroughs, whose first Russian editions of Giovanni’s Room and Naked Lunch came out with my introductions… While exploring my own sexuality, I was exploring Moscow’s gay underground, with its first speakeasy bars, discos and bohemian salons, where I met many fantastic artists who later on became the stars of post-Perestroika art—Timur Novikov, Sergei Bugaev-Afrika, Vladik Mamyshev-Monroe, Oleg Kulik, and Andrey Bartenev among them. It was my initiation into the queer underground and the very beginning of my own artistic path. In retrospect, Moscow of the early 1990’s reminds me of Weimer Berlin of the 1920’s. It was a fleeting moment of freedom before the brutal crackdown that followed with Putin coming to power. I consider myself lucky to have lived through it and be able to tell my story.

HOH: It seems that you had much success as young man but then were charged with crimes, which I am sure carried serious consequences but sound so foreign to someone raised in the US: “malicious hooliganism with exceptional cynicism and extreme insolence,” “inflaming social, national, and religious division,” “propaganda of brutal violence, psychic pathology, and sexual perversions.” What did you do to garner these charges? You say that you were forced to flee your county. What was going to happen if you didn’t leave?

SM: These Orwellian charges were routinely used against dissidents back in the Soviet times and, most recently, against the members of the feminist punk band Pussy Riot. If found guilty of all charges, I could face a prison sentence of up to seven years. Being an openly queer dissident, to be thrown to Russian jail would basically spell out my death sentence. I was continuously harassed by the Russian authorities over a period of 3 years prior to my departure, and eventually my lawyer advised me to flee the country and seek political asylum. At the time I was only 21 and it seemed like a very dramatic, if not impossible, decision to make. I had an open invitation from my friends at the French Embassy but I chose asylum in the US, since my boyfriend at the time was an American and I didn’t speak a word of French. I flew to New York with an invitation from Columbia University for a series of lectures and immediately filed for the asylum. The rest is history.

HOH: Much of the writing in Food Chain seems to be autobiographical. How much is true and how much is fiction? Are the stories or the real actions what led to the criminal charges?

SM: I was prosecuted for my journalism, which is not included in this book. More specifically, I was prosecuted for my articles and interviews dealing with gay issues and the war in Chechnya, but the main reason was the fact that I came out and outed several prominent personalities and politicians, including the right-wing leader Vladimir Zhirinovsky, at the time when homosexuality was an absolute taboo in the Russian media and psyche. And even though homosexuality was officially decriminalized in 1993, the general homophobic atmosphere prevailed both in press and politics. The official harassment only escalated after my 1994 attempt to register officially the first same-sex marriage in Russia, which is also described in the book. Naturally, it was a failed attempt; it made headlines around the world but turned me into a total pariah and my life into living hell, with late-night visits from the police and plain-clothed detectives and 24-hour surveillance. I could no longer publish my work, and two of the newspapers that I was most closely associated with were shut down and lost their publishing license. My last court hearings were televised on national TV, and the government press condemned me as “an agent of Western porn and drug trafficking” and called for my arrest and compulsory psychiatric treatment. Little did they know, that years later, after getting my political asylum in the US, I did, in fact, engage myself in the porn industry—first as a model and actor, then as a photographer for the magazines like Honcho, Inches, and Playgirl. That’s how my photographer’s career really took off… lol!

HOH: You give the impression that your had a very sexual life as a young man. Is that true? Why do you think that was? Were your peers having such an active sexual life?

SM: I just turned 40 and I must say that one of the advantages of getting older is that you don’t spend as much time on sex as you do in your youth. I used to think about sex 24 hours a day and it got me into many troubles, which you can find out from reading Food Chain. But sex also helped me to meet people and travel places, and sometimes paid my bills. Nowadays making art for me is just as exciting as making love, and I learned how to channel my kinky fantasies and fetishes in my work. Being a photographer, I do tend to meet a lot of attractive horny guys who are comfortable with their bodies and sexuality, but I find it more satisfying to photograph them than to fuck them. Ultimately, as the title text of Food Chain reads, “You’re what you fuck. You’re who you eat.”

HOH: The stories are very intimate. How do you feel about putting this part of your life out there?

SM: Publishing new work is always exciting and nerve-wracking at the same time—it’s like putting your guts on display. But once you have this new body of work published, you can forget and move on, leaving behind the emotions and experiences—both good and bad—documented, dissected and reflected upon… I find it very cathartic and therapeutic.

HOH: The stories are poetic. However, many were written in your native Russian and then later translated into English. How happy are you with the way the stories ended up?

SM: It was a challenge to find translators who were willing and able to work on my writings because of the subject matter, which is pretty explicit and graphic, as well as the slang and deconstructed grammar. It took nearly 20 years to put these translations together and edit them in a cohesive and meaningful way, and I couldn’t be happier with the way Food Chain has come out. I think of this book as an illustrated novel with every chapter written in its own style, from my early teenage poems and manifestos to the latest short stories written in my adopted language and texts made of cut-up newspaper headlines.

HOH: Your current creative practice is in many ways connected to your partner Brian Kenny. How do you influence each other's work as artists?

SM: Brian and I have been collaborating from the day we met. We come from very different backgrounds and we’re very different both artistically and on a personal level. Even our horoscopes say that we aren’t compatible, but 10 years later we’re still enjoying living and working together, which is not always easy. Every relationship is about give-and-take and I think our differences and talents complement each other in a very dynamic way, which allows us to become a third person or The Third Mind, as Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs called their life-long collaboration. We call it SUPERM.