or The Story of My Exile from Russia

"Bastard Mogutin! For a long time I had a suspicion that you were a nasty shit and a greasy, hidden Jew. Your writings are disgusting! Who gave you, reptile, the right to write this stuff? All kinds of faggots like you want to destroy our Orthodox country and corrupt our children. It will never happen! Our power is still strong! And tell this to your employers (or fuck buddies?) in Washington and Tel-Aviv! You have signed your own death warrant. Watch out now! If you are so courageous and principled, why do you hide under an idiot's pseudonym and why don't you disclose your real (Jewish) name? I can answer: you are afraid of the revenge of the Russian people who have been offended and mocked by you! But remember: we are sick of your rotten provocations! Enough is enough! Death! Death! Death!"

I received this letter shortly before I was forced to leave Russia in March 1995. At the time I was only twenty-one, and had no desire to leave my country for good, as my heart and soul were in that culture and language. I got used to these kinds of homophobic and xenophobic messages, as I had received them regularly through the mail and over the phone, but this one arrived via fax, in a country where fax machines were still very rare.

However, these anonymous threats were not that frightening compared to the threats from the state authorities and the police in response to what I wrote or said. So what exactly made me so dangerous for the Russian authorities at such a tender age? The answer is simple: I happened to be one of the first openly gay people in this vast country of 150 million people, and the first openly gay journalist in the Russian media.

A third-generation writer, I have been writing poetry since my teenage years, and my greatest ambition was to leave my mark on the history of Russian literature. Shortly after I left my family and moved to Moscow at the age fourteen, I began working as a freelance journalist for the first independent Russian newspapers, publishers and radio stations. When I first came out and began writing on gay issues, homosexuality was still a taboo subject in the Russian media, culture, and public life. Perestroika and Glasnost did little to change this situation. At the time of my arrival in the Soviet capital, gay life in Moscow was completely underground and consisted of speakeasy saloons, and several cruising spots around the Red Square and Bolshoi Theater, which were the subject of regular police raids and gay bashings.

Despite Yeltsin repealing the infamous law put in place by Stalin punishing homosexuality with up to five years in prison in 1993, gay men in Russia still feared harassment and imprisonment. Homophobic persecution remained a tacit state policy, with homosexuality considered morally abhorrent and unacceptable by most Russians. As recent polls have shown, almost half feel that homosexuals should be killed or isolated from society. Official decriminalization allowed some freedoms and, despite continuous harassment from the police, the first gay bars and discos opened in Moscow and St. Petersburg. There were several unsuccessful attempts to hold the first Russian Gay Pride parades, and the first Russian gay activists emerged.

Needless to say, coming out in the mid-1990s was not an option for most Russians. The absolute majority of gays and lesbians, especially in the provinces, were deeply closeted and married with children. The foreign journalists who interviewed me in Moscow told me that it was difficult for them to find any Russian gays or lesbians who would agree to show their faces or give their real names, even for the Western media. My being openly gay was shocking for the closeted journalists and editors in the Russian press, who supported me at the beginning of my career, but then turned their backs on me. "Don't push gay issues," one editor advised me privately: "I don't want to lose my job for publishing your articles, and my wife will think I'm a queer."

FROM RECOGNITION TO SURVEILLANCE

Having gained notoriety for my pro-gay journalism, I became a sore in the eye of the official censors. For example, one of my articles, "Homosexuality in the Soviet Camps and Prisons" published in the mainstream political weekly Novoye Vremya, was heavily censored by the editor, Leonid Mlyechin. What he excluded concerned homophobia among anti-Soviet dissidents. [1] "Even if it's true that those dissidents were homophobic, it's still not a good reason to kick them!" said Mlyechin. Other “editors-censors” were just as merciless and followed the popular belief, shaped by the old Soviet propaganda, preaching that there are no homosexuals in Russian or Soviet history; homosexuality is a "foreign disease" and, as the conservative writer Valentin Rasputin stated, "it was imported into Russia from abroad.”

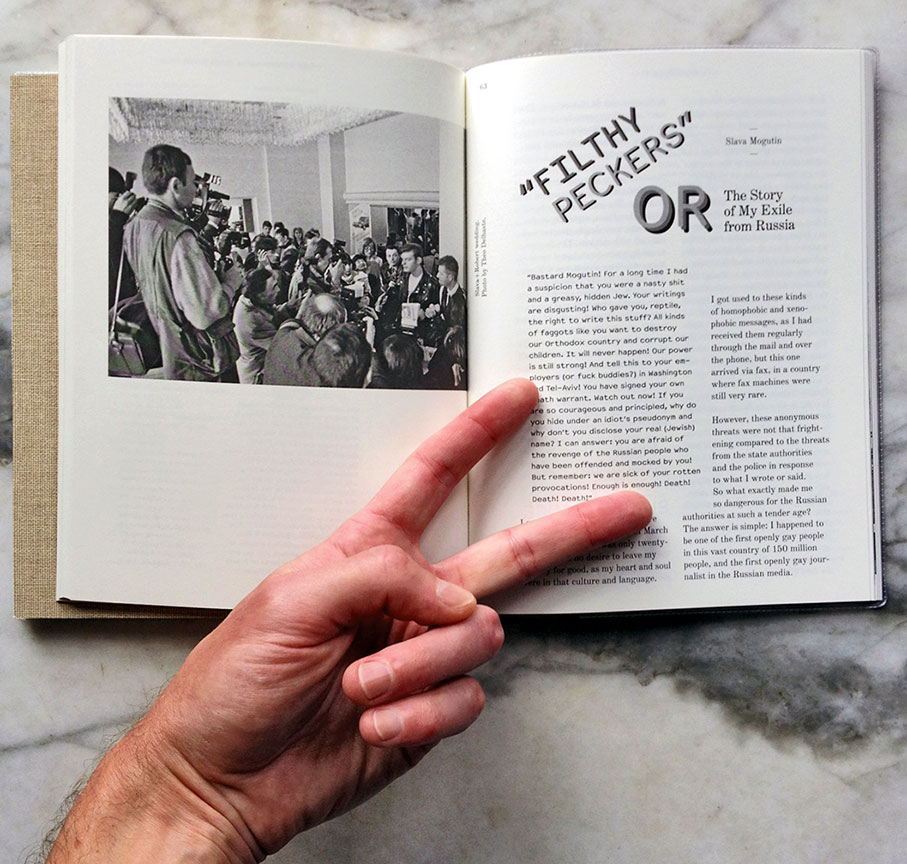

In July 1993, I published an interview with a flamboyant Russian pop star, Boris Moiseyev, one of the few openly gay personalities in Russian showbiz. In an interview entitled “Filthy Peckers of the Komsomol Leaders” Moiseyev revealed that at the outset of his career he was the victim of "sexual terror" by certain high-ranking Komsomol and Communist Party officials, who were "fans of the beautiful bodies of young guys." He graphically described how during the Moscow Olympic festivities in 1980, he was forced to strip-dance in front of a group of the Komsomol leaders and later performed oral sex on "the filthy peckers of those old bastards... all of whom are still in power.”

The interview with Moiseyev caused a huge scandal. It was first published in the independent Latvian newspaper Yeschyo, and was later reprinted in several other newspapers, including the mainstream daily Moskovsky Komsomolets and independent weekly Novy Vzglayd. I saw xeroxed copies of my interview being distributed in samizdat, like anti-Soviet literature in the USSR before Perestroika. When the scandal reached parliamentary level, criminal charges were brought against me under Article 206.2 of the Criminal Code ("malicious hooliganism with exceptional cynicism and extreme insolence").

The Regional Moscow Prosecutor accused me of using "profane language and obscene expressions, and graphic descriptions of sexual perversions, illustrated with a photo of a homosexual nature." Ironically, I found out about the Prosecutor's desicion from the press. The notorious Article 206.2, with a penalty of up to five years imprisonment, was routinely used against dissidents by the Soviet authorities. [2] Following the Soviet prosecution system, the same charge of ''hooliganism'' had been used against homosexuals in China and Cuba.

In October 1993, right after the attempted coup, the Yeltsin government shut down those newspapers it proclaimed "oppositional." Surprisingly enough, Yeschyo, which had initially published my interview with Moiseyev, was on that blacklist. On October 6, a group of militiamen headed by detective Matveyev showed up at the door of Aleksei Kostin, the paper's publisher. Without an official warrant they searched the apartment and arrested Kostin. For three days he was held in custody without any formal charges. "We should have gotten rid off you perverts a long time ago!" detective Matveyev exclaimed, referring to the newspaper's explicit content.

Yeschyo was singled out from the rest of the new independent media, because it was the only paper in Russia to regularly publish positive and non-biased material on gay issues. The government’s repressive actions were a part of a new backlash of homophobia, and a broader campaign against the freedom of speech and press. This campaign was enthusiastically supported by the official and conservative media, where a series of homophobic articles appeared against me and other journalists from Yeschyo and Novy Vzglyad in the following weeks. One author accused me of being an "agent of the Israeli secret service MASSAD, carrying out instructions to corrupt Russia.”

On October 28, 1993, three policemen showed up at the office of Glagol Publishing where I worked at the time and shouted through the door to Alexander Shatalov, its editor-in-chief, inquiring as to my whereabouts. He answered that I was not in. They threatened to break in and conduct a search. They had obviously been informed that I was at the office at that time. When they finally barged in, their leader introduced himself as Lieutenant Andrei Kuptsov. He showed me the order for my arrest. I was handcuffed and driven to the regional police station, during which I listened to the homophobic slurs of the cops, which were far more “profane and obscene” than the ones I had allegedly used in my article.

At the station I was interrogated by Kuptsov for five hours without a break or the presence of a lawyer: first as a witness to the crime (i.e. writing and publishing my article); then as the prime suspect; and, finally, as the one charged with committing the crime. He asked if I understood that the content of "Filthy Peckers" was illegal and that by writing it I had broken the law. I answered that this whole case seemed absolutely absurd. At the end of the interrogation I was forced to sign a document prohibiting me from leaving Moscow. "You're lucky we don't put you in custody like Kostin!" Kuptsov said to me. I did not have the right to travel and was, for all intents and purposes, under house arrest. Being under continuous criminal investigation and surveillance, I was also banned from leaving the country or receiving my foreign-travel passport.

Later, I found out that on the same day Kostin was also arrested. He was charged under Article 228 of the Criminal Code: "promotion, production, and distribution of pornography," subject to up to three years in prison. In the old Soviet times this article was also regularly used against dissidents for making and distributing samizdat literature. Three months later Kostin was arrested again and placed in a general holding cell in Butyrki, the most notorious prison in Moscow. Despite the considerable press attention given to his case, along with numerous letters of protest from Russian and international human rights organizations, Kostin was held in prison for thirteen months without trial.

The day after my arrest, Genrikh Padva, Russia's most prominent human rights lawyer, took on my case pro bono. His held authority due to the role he played representing dissidents and their families in several high-profile political trials during the Soviet era. Padva was the founding father of the first professional lawyers' union in the USSR and the first lawyer to petition the Ministry of Justice to end the anti-homosexual Article 121.1 of the Criminal Code. [3]

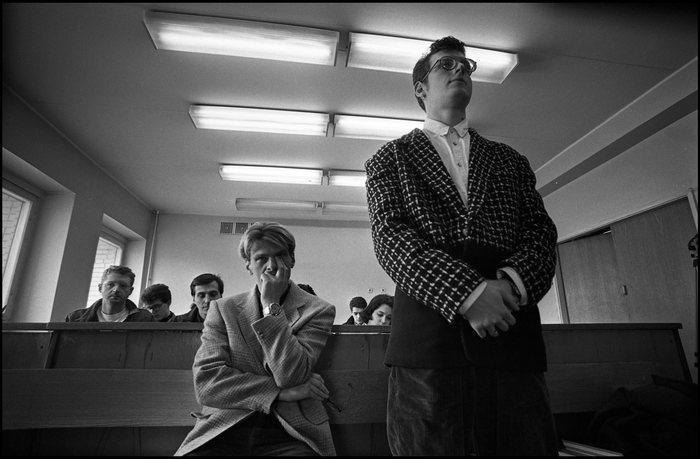

Slava Mogutin after the first arrest, Moscow, 1993 (photo by Laura Ilyina, CC-BY-SA-4)

Slava Mogutin after the first arrest, Moscow, 1993 (photo by Laura Ilyina, CC-BY-SA-4)

OUT COMES ZHIRINOVSKY

Around this time, at an art opening in Moscow, I was introduced to Vladimir Zhirinovsky, the notorious right-wing leader of the so-called Liberal Democratic Party. He ran for president in 1991 in Russia's first free elections and became one of the most popular politicians, thanks to his nationalistic slogans. His eccentric image and populist speeches made him an idol for many teenagers, and he was often invited to the openings of rock clubs and art galleries.

Zhirinovsky was with his bodyguard who, as he proudly announced, used to be the bodyguard of Babrak Karmal, the head of the Soviet regime in Afghanistan. [4] Much to my surprise, Zhirinovsky was very enthusiastic about meeting me and revealed to me that he read some of my articles. "So why didn't you come to me before?" he exclaimed. "You could have come to me and said: I want to work for you and your party! Why didn't you do it, like so many other young Russian guys have?"

It was hard to determine whether he was joking or not. Zhirinovsky invited me to join him at the restaurant at the Central House of Architects. There he pursued two teenage boys, fifteen or sixteen years old, and asked me to invite them to our table: "They can be good party members! I bet they will look great in military uniforms!" His manners, toasts, and speech, seemed totally bizarre. He felt comfortable in my company, as he knew I was gay. He offered vodka to the boys, but they declined. He openly flirted with them, but succeeded only in scaring them off. Disappointed, Zhirinovsky shot down another glass of vodka and went off to the dance floor into a clutch of young female admirers.

Zhirinovsky's interest in young guys is not a secret to his inner circle, but it’s never to be discussed. The issue of his sexuality is seemingly a taboo for the Russian press as well. Even when a Reuters photo surfaced of Zhirinovsky kissing a Serbian soldier on the mouth, both naked in the sauna, it was mostly perceived as a sign of solidarity with Serbia at the time of the NATO aggression. Always escorted by handsome young men—the members of the youth division of his party, Sokoly Zhirinovskogo (Zhirinovsky's Falcons)—he lived separately from his wife and spent weekends at his private dacha outside Moscow. One young reporter, who was invited to interview Zhirinovsky, told me that he was instead propositioned by Zhirinovsky to pose naked in the shower so that he could photograph him.

I received a different proposition from Zhirinovsky: he wanted me to become his press secretary. My reputation as an openly gay journalist obviously didn't concern him. Perhaps he just wanted to use my name in order to score more votes from my readers, as well as gay people. I realized that working for Zhirinovsky could put an end to my persecution and protect me from other possible troubles with the authorities. I was an easy target, as I had no political backing or protection. One telephone call from Zhirinovsky to the Prosecutor's Office, and the criminal case against me would be dropped. But I declined his offer, as I wanted to remain independent from all political parties, groups, or organizations. In retrospect, I would say that it is almost impossible to be politically independent in today's Russia.

Two months later, in December 1993, after an incredibly successful political campaign in the parliamentary elections, Zhirinovsky became the leader of the largest faction in the new parliament. With his promises of cheap vodka for every man, a boyfriend and flowers for every woman, and legalized drugs for all, he was the first politician in Russian history to use slogans in support of private life for all citizens, including homosexuals. As a result, a significant part of his 12.3 million voters were gay.

"We are against any interference in the private lives of our citizens," Zhirinovsky proclaimed in an interview. "One person might be fascinated by Eastern religions, another spends all day standing on his head doing yoga, and someone else has particular sexual preferences. Why do we have to interfere in their private lives? We don't want to! The American president had the same slogan. And I was the first Russian politician who did the same, wasn't I? That's a good thing! And note my, let's say, progressive ideology."

When asked about me and what he thought of my reputation, Zhirinovsky answered diplomatically, "We have a lot of work now, and we need people. That's why I proposed to work with him [...] You can find some discriminative characteristics on everyone: one—dirty; another—poor; the third one—stupid; the fourth one has a different religion; the fifth one has a different ideology [...] And who's left?" [5]

THE MARRIAGE

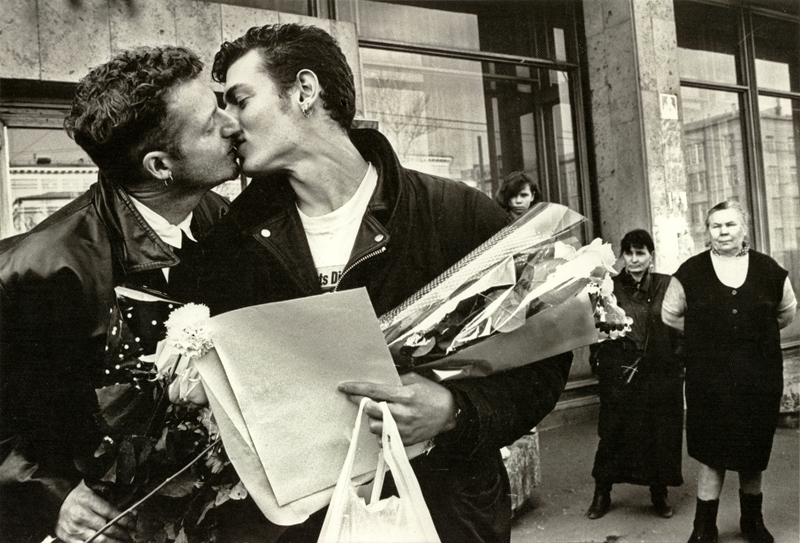

Slava Mogutin & Robert Filippini at the Wedding Palace No. 4, Moscow, April 12, 1994 (photo by Theo Delhaste, CC-BY-SA-4)

Slava Mogutin & Robert Filippini at the Wedding Palace No. 4, Moscow, April 12, 1994 (photo by Theo Delhaste, CC-BY-SA-4)

A few months passed by and my troubles continued. On March 22, 1994, the Presidential Legal Commission on Informational Disputes, the government censorship body, held a hearing regarding my articles published in Novy Vzglyad weekly. The Commission concluded that I was "a corrupter of public morals, a propagandist of pathological behavior, sexual perversions, and brutal violence" and that my writing "produced especial danger for children and teenagers." Since I was not invited to my own hearing, I learned the verdict from a government newspaper. It basically spelled out the end of my journalistic career. From that point, only a couple of liberal newspapers continued to publish my work.

During this turmoil, I had been dating an American artist, Robert Filippini, who was a member of Act Up and Queer Nation and co-founder of AIDS Infoshare, Russia’s first AIDS support group. Robert was actively involved in the emerging Moscow art scene and his studio on Mayakovsky Square was a popular meeting place for young Russian non-conformist artists, many of whom were gay.

In April 1994, after a few months of dating, we decided to stage the first same-sex marriage in Russia and attempted to officially register our relationship. The marriage was announced in the press as a conceptual performance and we were concerned that the authorities would try to stop it. In the press release we explained that the performance was a "protest against the policy of homophobia and sexism, puritan public opinion and hypocritical morality," and the primary objective for us was “to draw public attention to the problems of gays and lesbians in Russia."

On the eve of our marriage, we went to the United States Embassy to register Robert's intention to marry me, as per the rules regarding marriage of foreigners and Russian nationals. To our total surprise, even after telling the consul to take note of the genders involved, we received the certificate with the signature and stamp of the Embassy consul, Paul Davis-Jones.

On April 12, 1994 (which happened to be my twentieth birthday and Russian Cosmonautics Day) we arrived at Wedding Palace No. 4, the office for registering international marriages in Moscow. A large crowd of reporters and friends were waiting for us there. Karmen Bruyeva, the head of the Palace for over twenty-five years, was informed about our visit by a Russian television crew who were filming the event. Despite our expectations, she was polite and sympathetic.

Ms. Bruyeva said that personally she understood our desire to get married, but "marriage is a voluntary union between a man and a woman," according to a Soviet law that has remained unchanged since 1969. "I'm really sorry, but I cannot register your union. If I accepted an application from two men, I would be fired and the marriage declared invalid," Bruyeva said. "Why don't you petition to the parliament to amend the law?" Then she addressed the reporters, “Raise your hands those of you who favor amending the law," and all of them raised their hands.

Although doomed to be unsuccessful, our marriage attempt drew a huge public response. Even before the Internet, the event made headlines around the world. Most of the Russian press was sympathetic, except for a couple of homophobic articles in government papers and the communist Pravda, where Robert and I were labeled as "agents of the Western drug trafficking and porn industry." [6]

Slava Mogutin & Robert Filippini outside of the Wedding Palace No. 4, Moscow, April 12, 1994 (photo by Laura Ilyina, CC-BY-SA-4)

Slava Mogutin & Robert Filippini outside of the Wedding Palace No. 4, Moscow, April 12, 1994 (photo by Laura Ilyina, CC-BY-SA-4)

THE TRIAL

The trial of the criminal case against me was set for April 14. On the eve of the trial, Robert and I became targets of the police harassment. That night, two uniformed cops came to our apartment on Arbat Street, and explained the reason for their visit: they had received letters of complaint from the neighbors claiming that we "had corrupted our neighborhood." After looking around the apartment they left.

A few hours later, two plainclothes detectives came to our apartment. The lead man, stout and with a prominent scar on his face, demanded to see our documents. When we asked to see their identification, Scarface responded, "Fuck off!" He and his partner, a pretty brute, both wearing long black leather jackets, stormed into our kitchen and began a thorough interrogation about every aspect of our lives. Again, they told us that they had received a letter from a neighbor, falsely accusing us of holding "orgies with young boys", and then ranted on about their loathing of homosexuals and what they perceived to be the farce of our marriage attempt. "We can do anything with you two: put you in a psychiatric clinic, send you to jail, or deport you from Russia! And neither the PEN Center nor the American Embassy will be able to help you!" Scarface boasted.

At some point, the cops bragged about being members of Zhirinovsky's party. Their belligerence was unrestrained until I told them that I knew Zhirinovsky personally, and that I could call him immediately to have him stop them from harassing us. "Don't give us this bullshit!" Scarface yelled. "How can you, a queer, know Zhirinovsky personally?" In response, I showed them his business card with his hand-written private number that I happened to keep in my wallet. This seemed to have a chilling effect on them and, after finishing a bottle of our vodka and extorting 250 dollars from us, they finally left the apartment, laughing and promising to put an end to our "troubles with the neighbors". The visit was utterly animalistic. Both Robert and I were shaken and absolutely demoralized, to the point that we were afraid to even tell our friends about the incident.

On April 14, 1994, the Presnenskyi Interregional Court held a hearing concerning the criminal charges brought against me under Article 206.2. In violation of due legal process, I received no official notification for the date of my trial. I wasn’t even familiar with the documents of my case or the final indictment. When I protested this to the presiding judge, Elena Fillipova, she was completely indifferent. Genrikh Padva, my lawyer, argued that I was targeted for prosecution because of my homosexuality. He said that this was the only case in the history of Soviet or Russian jurisprudence when a journalist had been charged with "hooliganism" for his use of language. Use of so-called profane language has a long tradition in Russian literature and it has become increasingly common in the media. Padva mentioned a few examples when presidents Gorbachev, Yeltsin, and other Russian officials used profane language in their speeches. He argued that the case should be dismissed because of a series of violations on the part of the Prosecutor's Office. In conclusion, Padva stated that this wasn’t just "a minor case, but an open violation of human rights."

After my lawyer's speech, Judge Filippova took a break for "consultation," which was odd, as she was alone in her chambers. Evidently, she "consulted" with the Prosecutor's Office or other high-ranking initiators of the case against me. Even though the new Russian constitution states that the judicial system is to be independent, in today’s Russia, judges still represent the Prosecutor's Office. After about forty minutes, the judge returned and read her resolution. She found me guilty of all charges, but sent the case back to the Prosecutor's Office for a new investigation, on technical grounds.

On the night of April 16, the two detectives returned. For the next two hours a vodka-drinking Scarface—whose profanity-filled speech was a curious mix of foul Russian, English, and German—told graphic sexual stories and spoke of politics, religion, the philosophy of Hegel, Zhirinovsky's glory, the Motherland, the Orthodox Power, family life, his poor old mother, the dangers of his tough job, and the general moral disorder and decay of the world. Throughout, he emphasized his hatred of homosexuals and the corrupting influence of the West. Thus, I discovered the intricate spiritual and intellectual world of a Russian cop. Midway through this monologue a large cellophane bag of hashish was laid on our table. The detectives laughed and proceeded to warn us of the prison terms dished out to those found in possession of drugs. They then offered to find some young girls to bring up to our apartment for group sex. Pretty Brute asked if we preferred eleven- or twelve-year-old girls. Repeatedly during their visit, both of them demanded money from us. Again, they left the apartment drunk to the point where they could hardly walk.

A couple of nights later Scarface returned alone. He showed us a handwritten letter full of homophobic scribblings, describing graphically orgies with young boys that supposedly took place in our apartment. He asked if we wanted him to kill our "motherfucking" neighbor, the alleged writer of this letter. He raised his full glass of vodka, swilled it and said that he would now do us a favor, at which point he burned the letter in front of us, filling the room with smoke and yipping as he singed his fingers.

After the extensive press coverage our attempted marriage received, we were frequently recognized and regularly stopped on the street by the police. This was especially true in our neighborhood, where we couldn't pass by the roving cops without being harassed. Though the anti-homosexual law had been abolished in Russia, the police continued to collect files on known homosexuals. "I control all of them in my district," the Moscow police chief said in a TV interview. "I have to do it, because homosexuals are physically and mentally abnormal people. Every one of them at any time could pick up an ax and just kill somebody. Easily! They have to be isolated. They are sick!"

Slava Mogutin and the publisher of Novy Vzglyad Yevgeny Dodolev on trial, Moscow, 1994 (photo by Laura Ilyina, CC-BY-SA-4)

Slava Mogutin and the publisher of Novy Vzglyad Yevgeny Dodolev on trial, Moscow, 1994 (photo by Laura Ilyina, CC-BY-SA-4)

FLIGHT FROM RUSSIA

On September 20, 1994, under pressure from legal efforts, the liberal press, and Russian and international human rights organizations, the criminal case against me was dropped by the Prosecutor's Office, because, "due to changed circumstances, Mogutin has ceased to pose a danger to society." I only learnt of the decision on October 10, when I was invited to the Prosecutor's Office and had a three-hour conversation with Igor Konyushkin, First Deputy Prosecutor of the Office.

Comrade Konyushkin introduced himself as a "big fan of my writing." Tall and thin, he chain-smoked nervously throughout our conversation. He seemed too young, too intelligent, and too gentle for his job. He spoke with me very frankly and seemed outwardly friendly, although soon enough I realized that this was a mere provocation. "Because of my job, I had to read all your articles," Konyushkin said. "We have a huge file on you. You might be a good writer but the content of most of your articles is criminal. We could open a new case against you concerning anything from these articles as easily as we did with the "Filthy Peckers" case. I just want to let you know that, although we dropped this case, we can always open another one. We're giving you a chance to rehabilitate your mind: you must stop your writing or change your subject matter! You know what I mean? That's my advice as your biggest fan!"

My conversation with Konyushkin reminded me of Nabokov's Invitation to a Beheading, a masterful Kafkaesque tale of a torturous relationship between the prisoner and his executioner. There was something sadomasochistic about Konyushkin’s obsession with my journalism, with my criminal prosecution being an extension of this obsession. Konyushkin told me that he was particularly outraged by an article in which I wrote that homophobes in the Prosecutor's Office were just repressed queers. After my bizarre conversation with him, I was all the more convinced that what I had written was true. [7]

A few weeks later, the State Prosecutor's Office issued a statement proclaiming their disagreement with the Regional Office's decision to close my case, and they brought it into their jurisdiction for future prosecution.

In February 1995, the Presidential Legal Commission on Informational Disputes held two more hearings concerning my journalism. Both hearings were closed to the press and public; only reporters from the government press were allowed. The trial was carried out in typical Soviet style: when I tried to say something in my defense, the microphone was turned off. The Commission’s members and the reporters just laughed at my protests. The chairman, Anatoly Vengerov, a washed-out ex-communist apparatchik in his sixties, was screaming at me: “It’s scandalous! Stop this ugliness immediately or we shall call the police! Where is security? Somebody, call security right now!”

This time, the members of the Commission accused me of violating the Constitution by “inflaming national, social, and religious division” (Article 74 of the Criminal Code) and recommended to the Prosecutor’s Office that new criminal charges should be brought against me, and that the Committee on Press and Information should shut down Novy Vzglyad and rescind its publishing license. The Commission’s decision was announced on prime time news and published in government papers.

I was almost unanimously vilified in press coverage of the new trial, in over a dozen aggressively homophobic articles. One of them called me a “hysterical mama’s boy” and appealed to the authorities to put me in a psychiatric clinic. Another reporter, the head of the Moscow Union of Journalists, suggested that it was too bad that the earring-wearing Mogutin hadn’t been killed instead of Dmitry Kholodov (the journalist of Moskovsky Komsomolets killed by a letter bomb in the editorial offices in October 1994 while working on a report on corruption in the Russian military). [8]

This three-year-long prosecution and intimidation campaign took its toll on me. I felt like a trapped animal. I was afraid of staying home just as much as being on the street,;waiting to be arrested again and harassed by the cops at any moment. On the advice of my lawyer, Robert and I decided to flee the country. Having received an invitation from Columbia University in New York to give a series of lectures, I went to the American Embassy in Moscow and, after revealing my story, got an entry visa. Expecting the situation to settle down in my absence, I fled Russia in the hope of returning in a few months. But shortly thereafter, I found out that a new criminal case against me had in fact had been opened under Article 74 of the Criminal Code, with a potential prison sentence of up to seven years. With that in place, returning home was no longer an option. I had no choice but to seek political asylum, eventually becoming the first Russian to be granted asylum in the US on the grounds of homophobic persecution. My case set the precedent and opened the door to many similar cases of gays and lesbians from Russia and other former Soviet republics. [9]

In Russia I left behind not just my political and criminal troubles, but also my language, audience, family, circle of friends, and my celebrity status. I had to start my whole life again from scratch. However, when people ask me how I find my present life, I tell them that being an anonymous political exile in New York is much better than being a famous gay writer in a Russian prison.

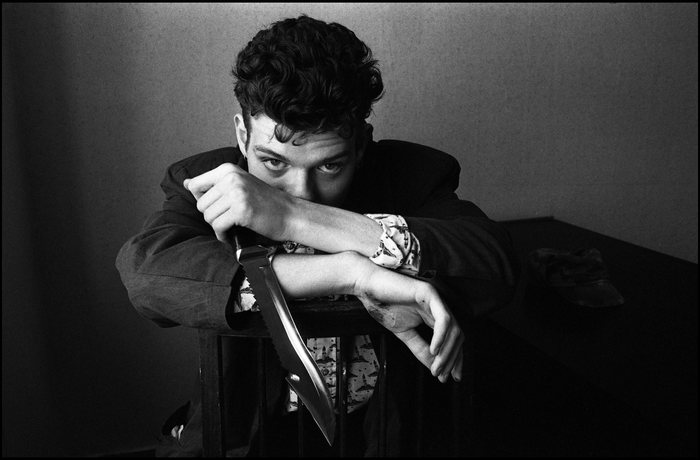

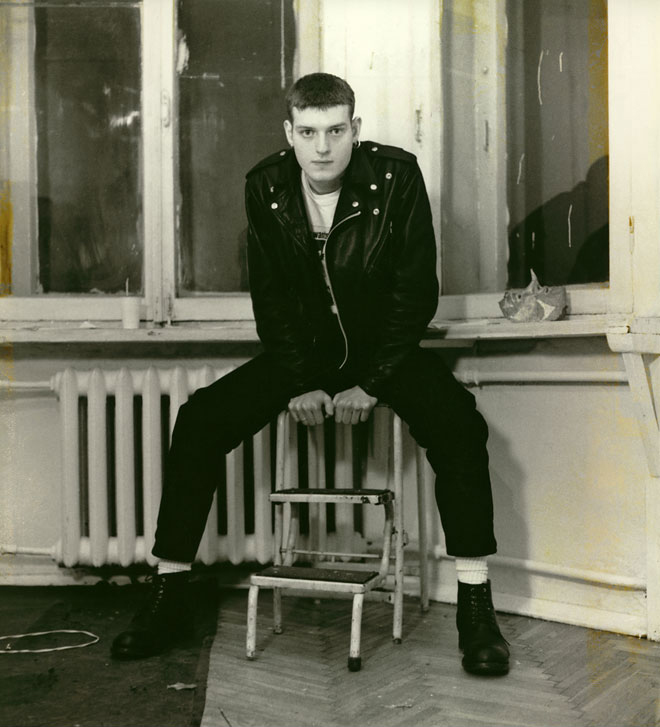

Slava Mogutin on the eve of his exile from Russia, March 14, 1995 (Photo by Vasiliy Kudryavtsev, CC-BY-SA-4)

FOOTNOTES

[1] The abbreviated English version of this article, “Gay in the Gulag”, appeared in Index on Censorship (UK), Volume 24, No. 1/1995.

[2] Two decades after my trial, the same charge of “hooliganism” was used against the feminist punk group Pussy Riot for their anti-Putin performance at the main cathedral in Moscow.

[3] In recent years, Genrikh Padva, now in his eighties, represented several high-ranking opposition leaders, including the anti-Putin oligarch-turned exile, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, and the families of the Russian Nobel Prize winners Boris Pasternak and Andrei Sakharov.

[4] In 1986, after 7 years in power, Babrak Karmal was sacked by the Gorbachev’s government. He died in exile in Moscow from liver cancer in 1996.

[5] Born Vladimir Volfovich Eidelstein in Kazakhstan, Zhirinovsky, who’s now in his late sixties, remains one of the most resilient and longest serving politicians in the modern Russian history. Widely seen as a Kremlin puppet oppositioner, he served as the Vice President of the State Duma (Russia’s Parliament) from 2000 to 2011. He also recorded a pop album and released his own vodka brand named after him.

[6] Following our example, over the last two decades there were several other unsuccessful attempts to register same-sex marriages by the Russian gay and lesbian couples, although they were barely covered in the Western media and largely ignored by the Russian media.

[7] About ten years after this conversation took place, I found out that my “biggest fan” Igor Konyushkin was allegedly bashed to death on the street in Moscow by two Chechen mobsters – or at least that was the official version.

[8] Dmitry Kholodov’s assassination was the first of many killings of journalists in Russia. He was only 27 at the time of his murder and his case was never solved.

[9] As a result of the recent anti-gay legislation adopted by Putin’s government, there are many accounts of the mass exodus of gay and lesbian refugees from Russia seeking political asylum in the US and the EU.