Queer Insurgency:

Slava Mogutin and the Politics of Camp

GRAHAM H. ROBERTS

Paris Nanterre University

ABSTRACT

The subject of this article is Russian-American artist Slava Mogutin. A close associate of Gosha Rubchinskiy and Lotta Volkova, Mogutin has been based in New York since 1995. While he originally shot to fame as a poet and novelist, Mogutin is today better known as a performance artist, filmmaker and photographer. The aim of my article is to locate Mogutin, and in particular his fashion photography, within current debates around the representation of masculinity and the construction of masculine subjectivity/ies. More specifically, using a visual analysis methodology, I analyse the camp aesthetics of Mogutin’s fashion imagery.

In a number of ways, Mogutin’s camp aesthetic raises questions about displacement and identity, the clash between individual desires and social norms and – as he puts it – ‘what it means to be a young man in the modern world’. It also constitutes an avowedly political challenge, not just to the state-sponsored homophobia and heteronormativity of Mogutin’s native Russia but also to the identity politics underpinning today’s fashion industry. I conclude by suggesting that Mogutin’s openly political form of camp might pose a challenge to the traditional Sontagian view of camp as apolitical.

INTRODUCTION: SLAVA MOGUTIN – ‘QUEER INSURGENT’

Journalist, performance artist, filmmaker and photographer, Siberian-born Yaroslav (‘Slava’) Mogutin is a quite exceptional character. Although just 18 when communism collapsed in the USSR, he rapidly made a name for himself as a news journalist in the immediate aftermath of that collapse. As the only openly gay personality in the Russian media in the early 1990s, he penned the prefaces to the Russian translations of a number of novels that had been banned by the Soviet regime, such as James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room (1957) and William S. Burroughs’s Naked Lunch (1959). In 1994, just a year after male homosexuality was legalized in Russia, he attempted to register the country’s first same-sex marriage with his then partner, American artist Robert Filippini (Mogutin 2021b; same-sex marriage remains banned in Russia). The following year, he became the first Russian to be granted political asylum in the United States on the grounds of homophobic persecution (Rosen 2017).

In the early 1990s, Mogutin had enjoyed a ‘meteoric’ rise to fame in Russia as a poet and a journalist (Chernetsky 2007: 171). While he continued working in these areas after emigrating, once in New York, he increasingly found other outlets for his creativity, ‘forced’ as he felt he was, ‘to abandon his mother tongue’ (LaBruce 2017: 177). He gradually turned from poetry to prose, and then from literature to the visual arts (Rosen 2017). At first, he was happy to work in front of the lens, rather than behind it. Not only his face but his body were much sought after by photographers and independent filmmakers alike; at one point he was in such high demand that in 2002 the US art magazine Index labelled him ‘Russia’s biggest export’ (cited in Chernetsky 2007: 175).

He eventually began working as a photographer in his own right and has collaborated with prominent figures in Russian visual culture and fashion, such as Andrey Bartenev (Vainshtein 2019), Lotta Volkova and Gosha Rubchinskiy (Roberts 2019). His first monograph of photographs, titled Lost Boys, shot in Russia and Germany and featuring photographs of young men striking poses that range from the homosocial to the pornographic, appeared in 2006 (Mogutin 2006; see also Fedorova 2013). It was around this time that Mogutin first ventured into fashion photography, when he was approached for a commercial advertising project by Tom Ford for Gucci.

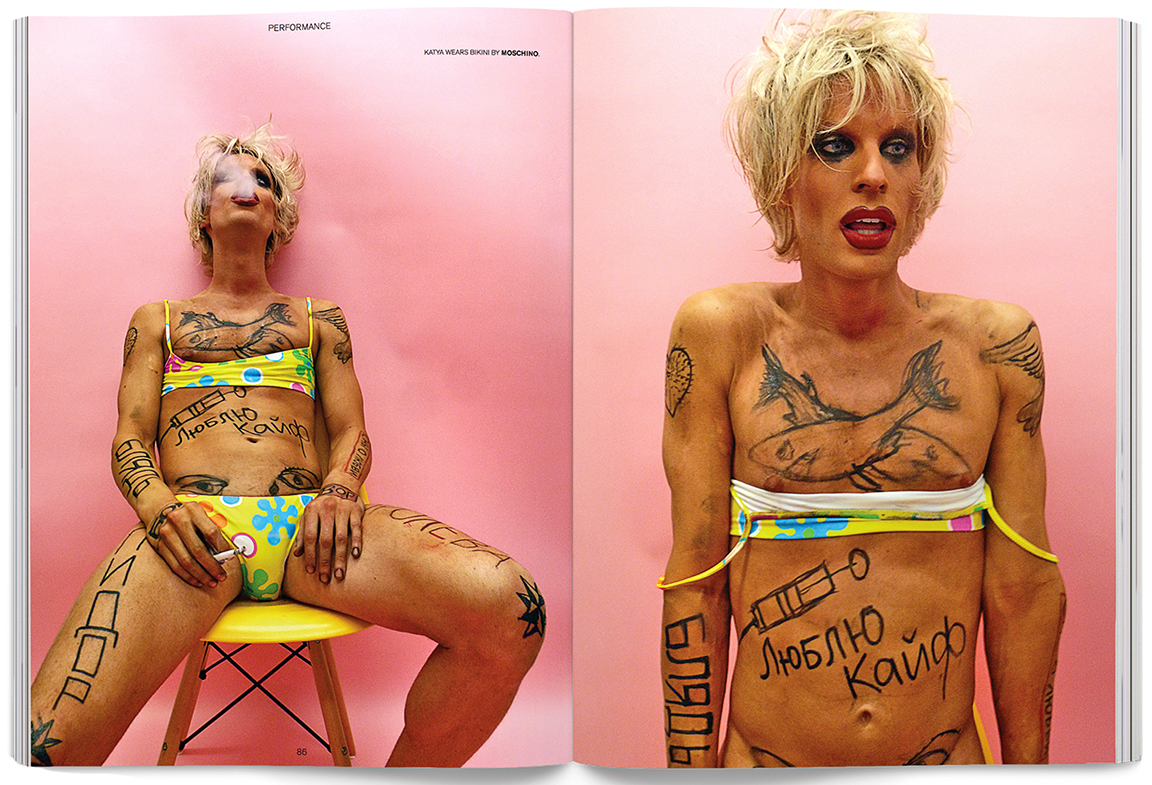

He continues to work in fashion today and recently produced a new edition in the Helmut Lang ‘Logo Hack’ collaboration, together with South African artist Jan Wandrag. He remains active in a remarkable number of other areas, however. These include journalism, performance art (most notably the SUPERM project co-founded in 2004 with Brian Kenny) and music video production. He has published interviews with several outlandishly queer celebrities such as Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, Christeene, Katya Zamolodchikova (Figure 1), Gilbert and George, and Edmund White (Mogutin 2021a).

Mogutin has been in vogue in contemporary western arts circles for some time now (Mogutin 2021c). His photographic work has been featured in a wide range of publications such as i-D, Dazed & Confused, L’Uomo Vogue, Stern, Libération, the New York Times and V Magazine (LVL3 2015). It is something of an exaggeration to suggest that Mogutin has become ‘an international arts celebrity’ (Chernetsky 2007: 180). What is indisputable, on the other hand, is that for the last decade or so Mogutin has used his position as a prominent artist to engage in a number of public debates. As ‘Russia’s greatest art rebel’ (Rosen 2017: n.pag.), he has been quite outspoken in three areas in particular. First, while he describes himself as a ‘Russian patriot’ (Mogutin 2021g: n.pag.), he has made a number of statements in the western media against what he sees as the institutionalized homophobia underpinning Putin’s regime (Kayvon 2017; Anon. 2019).

His call on the West to boycott the Sochi Winter Olympics of 2014 prompted the Franco-German television channel Arte to label him ‘the Russian Rimbaud’ (Arte 2017: n.pag.) – a reference to the most famous poète maudit of French nineteenth-century letters, a writer whose legacy Mogutin has himself invoked in his verse (Chernetsky 2007: 172). Second, he has been a vociferous opponent of online censorship. In 2016 he penned an ‘open letter to [Facebook founder] Mr. Mark Zuckerberg’ (Mogutin [2016] 2017).

When in December 2018 social media platform Tumblr deleted all ‘adult’ content from its platform, Mogutin responded by making a number of his more sexually explicit photographs freely available on the Tom of Finland website (Camblin 2019; Malley 2019). Most recently, Mogutin has added his voice to those of many others across the fashion world globally who are calling for greater body, ethnic and sexual diversity among catwalk models (Cordero 2019).

There are those inclined to dismiss such interventions by Mogutin as mere posturing. As Chernetsky puts it, for example: ‘[Mogutin] borrows from the self-fashioning practices, in both the literary and literal sense, of the Futurists and Dadaists, on the one hand, and of Andy Warhol as well as the punk tradition in styling and design, on the other’ (2007: 172). Many others, however, take a very different view. Getsy, for example, argues:

(2017: 89)

One work in particular in which Mogutin might be said to ‘conjure excess’ while demonstrating a ‘gleeful disregard’ for decorum is the video Moon River (Uncut), subtitled ‘Piss tribute to Marlene Dietrich’ (Mogutin 2021c; Dietrich famously performed this song at a concert at the Paris Olympia in 1962). In this eight-and-a-half-minute film, Canadian performance artist Bruce LaBruce shaves a young man’s head, before lying down in a bath and letting the young man urinate into his mouth – all accompanied by the eponymous melody (Mogutin 2015). Not surprisingly perhaps, given his close involvement in Mogutin’s work, LaBruce – part of Mogutin’s ‘own queer family’ (LaBruce and Mogutin [2016–17] 2021: n.pag.) – is also an ardent admirer of that work. As he has colourfully put it: ‘Slava Mogutin is the bastard child of Mayakovsky and Helmut Newton. He is the best kind of artist – the kind who creates because he needs to, and who painstakingly develops an aesthetic to express that need’ (Mogutin 2017: 177).

Linking Mogutin to two other notorious artistes maudits who challenged accepted norms, LaBruce’s comment echoes Getsy’s, quoted above. Soviet poet, playwright and agitator extraordinaire Vladimir Mayakovsky (1893–1930) was co-signatory of the Russian Futurist manifesto of 1912, with its call for art to deliver ‘a slap in the face of public taste’ (Erlich 1994: 32–55). Mogutin claims to have been ‘hugely influenced’ by Mayakovsky, as well as by other prominent Soviet cultural figures such as photographer Aleksandr Rodchenko (LaBruce [2009] 2021; Mogutin 2021g: n.pag.). As for fashion photographer Helmut Newton, he courted controversy in the 1970s and 1980s with images which, as Geczy and Karaminas argue (2016: 67), ‘stretch[ed] the limits of the representation of flesh [and] of gender’, with their provocative use of drag, BDSM imagery and even, in the case of Prada’s very first advertising campaign, of a ‘murdered’ woman’s ‘corpse’ (Geczy and Karaminas 2017: 61–62).

What links Mogutin to Mayakovsky and Newton most of all is an apparent willingness to shock, to challenge societal norms and the notion of ‘good’ taste underpinning those norms. Indeed, Chernetsky has gone so far as to suggest that Mogutin’s work represents what he calls an ‘anarchist subversion of all established social constructs and identities’ (2007: 173). Chernetsky is of course primarily referring to Mogutin’s literary output. Nevertheless, it is surely a desire to challenge normative notions of identity that has led Mogutin to work more recently with artists such as Katya Zamolochkikova (Figure 1; real name Brian Joseph McCook).

Chernetsky’s assertion is supported by a number of statements that Mogutin himself has made. As Mogutin robustly put it in a recent interview:

All of us [artists] have a social responsibility. Unless you’re a total and utter sheep. Artists have a perfect platform to express their views and challenge the status quo but most career artists never use that platform. [...] For me, it’s all about queer insubordination and insurgency, now more than ever. I transgress, therefore I am.

(Gutierrez 2017: n.pag., emphasis added)

One of the most interesting things here is Mogutin’s suggestion that it is first and foremost by virtue of its very ‘queerness’, by the way it transgresses societal and aesthetic norms, that his art is subversive. Indeed, such a claim lies at the heart of his manifesto, or ‘Artist Statement’, published on his official website:

At the time when our most fundamental constitutional rights are under attack, I believe that queer imagery can serve as the most effective weapon against hypocrisy, bigotry, and censorship. When they censor my work either on social media or in real life, my response is always – double up on the queer, double up on the fight and what they don’t want to hear or see.

(Mogutin 2021d: n.pag., original emphasis)

By the sheer gusto with which Mogutin carries his ‘fight’ to his opponents, he is surely one of the most iconoclastic visual artists working anywhere today. And yet for all Mogutin’s popularity (and at times notoriety) among the contemporary arts cognoscenti in Western Europe and North America (Mogutin 2021d), there is precious little scholarly work on his oeuvre. Moreover, what scholar- ship there is tends to focus on the man’s early literary output, to the virtually complete detriment of his work in other media (Essig 1999: 143–46, 155–56; Chernetsky 2007: 171–81; Marcadé 2008). The primary aim of my article is to go at least some way towards addressing this gap in the critical literature on Mogutin by looking at his visual imagery. More precisely, I shall discuss the ways in which he queers received notions of masculinity and masculine subjectivity in that imagery. As I propose to show, Mogutin, a self-styled ‘queer insurgent’ (Camblin 2019: n.pag.), demonstrates a quite specific aesthetic sensibility that makes him a ‘camp antagonist’ (Galvin 2017: 187).

While I shall focus on his fashion photography, I shall also at times discuss other images not explicitly produced as part of fashion shoots. This is because so much of Mogutin’s visual work crosses generic boundaries; on the one hand, many of his photographs for fashion magazines feature far more flesh than clothing, while on the other hand, much of his supposedly non-fashion imagery invites the viewer to focus on items of clothing as much as or even more than on the models featured in it. As Dams ([2013] 2021) has suggested, if much of Mogutin’s photographic imagery resists categorization, this is part of his attempt to confuse the viewer, to force them to confront the way in which assumptions about the category of a given image might shape the way they read that image.

I aim to place Mogutin’s work within the global framework of the contemporary ‘menswear revolution’ (McCauley Bowstead 2018). In doing so, I hope to contribute to the broader debates on the cultural representation of the male body, fashion and masculine subjectivities. For as Steele (2020) notes, fashion photography plays a significant role in disseminating normative notions of masculinity, even if – or perhaps because – the male body is a canvas onto which a myriad of conflicting cultural meanings may be mapped (Bordo 1999; Edwards 2006: 140–61). And as Brajato and Dhoest (2020: 58) suggest, part of the ‘power’ of men’s fashion, in particular, lies in its ability to impose ‘normative’ rules on, and of, masculine identity; ultimately this enables it to buttress hegemonic masculinity.

At the same time, as Sawdon Smith (2020) has quite graphically shown, echoing McCauley Bowstead (2018) and others, those rules are increasingly finding themselves ‘queered’ in twenty-first-century men’s fashion photography. To paraphrase Edwards (2006: 140), the represented – one might say fashioned – male body has lately become the site where the ‘performativity, normativity and reflexivity’ of masculinity are most hotly contested. Edwards’s point is particularly germane to Mogutin’s photographic work, much of which openly rejects hegemonic masculinity and its attendant heteronormativity. Before I discuss that work further, however, I need to say something about the conceptual framework I shall be using, and in particular my understanding of the term ‘camp’.

Figure 2: Slava Mogutin, ‘Tom Ford for Gucci’. Fashion editorial for Flaunt (US), fall fashion issue 57, 2004. Also appeared in Stern (Germany), Nr. 42, 2004 and TOM FORD, Rizzoli, NY, 2004 (Mogutin 2021e).

REIMAGINING THE MALE BODY: FROM ‘QUEER’ TO ‘CAMP’

As we have seen, Mogutin frequently portrays himself as a ‘queer’ artist, using ‘queer imagery’ as a ‘weapon’ to ‘challenge the status quo’ (LaBruce and Mogutin [2009] 2021: n.pag.). His penchant for what he calls ‘queer insurgency’ (Gutierrez 2017: n.pag.; Camblin 2019) may be one of the things that attracted him to work in fashion. There is after all a long tradition of queer activism in and around the fashion industry (Steele 2013; Sando 2020). As a tradition, however, it is a rather broad church, covering as it does what one might call a multitude of sins – from what activists themselves wear (Katz 2013) to how designers style their catwalk models (Geczy and Karaminas 2017; Roberts 2019).

As for just where Mogutin might see his own place in this very unholy pantheon, he is frustratingly coy on the subject. The closest he gets to proposing a working definition of his own brand of ‘queer’ comes in an interview alongside Bruce LaBruce for the UK-based fashion magazine Man about Town. At one point, Mogutin implies that ‘queer’ is a catch-all term for any imagery or document that ‘do[es]n’t fit into [the] rigid Victorian “Community Guidelines”’ of ‘the corporate moral police censor’. At another moment, when asked to describe his ‘perfect queer space’, Mogutin responds by recounting an episode in which he was given a ‘hot blowjob’ by an anonymous man on the steps of the Russian State Court building just around the corner from Red Square (LaBruce and Mogutin [2016–17] 2021: n.pag.).

So far so ... messy. Given the homoerotic quality of much of his work, Mogutin’s understanding of ‘queer’ seems very close to the definition given by Geczy and Karaminas. As they put it: ‘Queer [...] has now permanently shifted into the realm of social and bodily types that do not conform to a model that is “straight”, namely heterosexual, conventional and middle class’ (Geczy and Karaminas 2013: 2). Observing that it suggests ‘divergence from a rooted norm’, they maintain (2013: 3) that ‘queer’ is concerned with the ‘renegotiation, undermining, overstatement and reinstatement’ of all kinds of fixed identity systems. This assertion has been explored further by McCauley Bowstead, who has persuasively argued that ‘[q]ueering can be understood [...] as a way of fracturing hegemonic identities into more plural and diffuse subjectivities’ (2018: 124).

Not surprisingly perhaps, given the challenge it poses to all sorts of normative identities, ‘queer’ brings with it its own set of identity issues. As Lord (2019: 28) cogently puts it in her survey of recent queer art and culture, ‘“queer” comes loaded with meanings that are not entirely in our control’. And when it comes to representing – reimagining – the male body, ‘queer’ may well be in the eye of the beholder (Edwards 2006; Barry and Phillips 2016). Perhaps the biggest problem, however, is the fact that in cultural theory and fashion scholarship, ‘queer’ generally refers to a style, a praxis, rather than an aesthetic sensibility or sign system (Cole 2013; Geczy and Karminas 2013; Steele 2013; Cole 2015).

A possible way out of this hermeneutic impasse is provided by two recent articles that explore queer and more specifically the articulation between ‘queer’, on the one hand, and ‘camp’, on the other. In her article on Leigh Bowery’s Birth Scenes (1992–94), Galvin discusses what she calls Bowery’s ‘camp tactics of artifice, incongruity, theatricality, appropriation, failure and humour’ (2017: 187). Exploring Bowery’s performance of Birth Scenes in liminal spaces such as night clubs, Galvin looks forward to more recent work by Hitchcock and McCauley Bowstead (2020), who analyse the queer and camp elements of Charles Jeffrey’s LOVERBOY, with its very blurred distinction between night club and fashion runway. As they argue (2020: 30), quoting Malbon (1999), while ‘queer’ is about being-in-the-world, ‘camp’ is about how I imagine that world: ‘As an ethic, aesthetic and sensibility, camp’s emphasis on ostentation and theatricality, foregrounds the performative nature of identity while gesturing to the liberating nature of queer sociality, which is“less about rules and more about sentiments, feelings, emotions and imaginations”’ (Malbon 1999: 26, emphasis added).

As an aesthetic sensibility, camp has been with us for centuries (Bronksi 1984; Bolton 2019).Yet it is only relatively recently that the first serious attempt was made to conceptualize it. This came in 1964, in Susan Sontag’s famous series of 58 reflexions (Sontag [1964] 2018). Sontag explains the absence of any extensive discussion of the concept before the 1960s by pointing out that camp is above all a sensibility, and therefore ‘to talk about Camp [sic] is to betray it’ ([1964] 2018: 1–2). Be that as it may, Sontag has a lot to say about this sensibility over her 58 reflexions, referred to as ‘notes’. Camp for Sontag is all about taste and about challenging conventional hierarchies of taste: ‘The ultimate Camp statement: it’s good because it’s awful’ ([1964] 2018: 33). With its potential to destabilize gender and sexual identities, Sontag’s camp enthusiastically embraces androgyny – and it does so, furthermore, in the name of taste:

Camp taste draws on a mostly unacknowledged truth of taste: [...w]hat is most beautiful in virile men is something feminine; what is most beautiful in feminine women is something masculine.

(Sontag [1964] 2018: 9, emphasis added)

Hence Sontag’s assertion that ‘[t]he essence of Camp is its love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration’ [1964] 2018 : 1), that its ‘essential element’ is ‘seriousness, a seriousness that fails’ ([1964] 2018: 16).

While these ‘notes’ are necessarily the starting point for any scholar wishing to analyse camp, they have been repeatedly revisited and revised in the intervening half century since they were first penned (Booth 1983). In 2019, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art curated an exhibition titled Camp: Notes on Fashion (Bolton 2019a). Contributing an essay to the catalogue accompanying the exhibition, Cleto (2019) makes a number of important points that illustrate the relevance of camp to Mogutin. For Cleto, if camp is to have any kind of coherent meaning as a theory, that meaning is to be found ‘within a queer [sic], twisted, swinging, and troubling movement across distinctions, [and] in the trespassing of borders’ (2019: I/15). Quoting Sontag’s notes 10 and 11, in which she equates being-in-the-world with ‘Being-as-Playing-a-Role’ and argues for the interchangeability of ‘man’ and ‘woman’, ‘person’ and ‘thing’ ([1964] 2018: 9–10), Cleto continues: ‘[C]amp demystified the conventionality of gender roles, of the male/female as well as of other binary hierarchies – good/bad, high/low, true/false, nature/culture, object/ subject, etc. – which it playfully inverted’ (2019: I/37).

Figure 4: Slava Mogutin, ‘Sneaker Sniffer’ (Josh & Norbert), New York City, 2003 (Mogutin [2004] 2021).

MOGUTIN’S FASHION IMAGERY: THE POLITICS OF CAMP

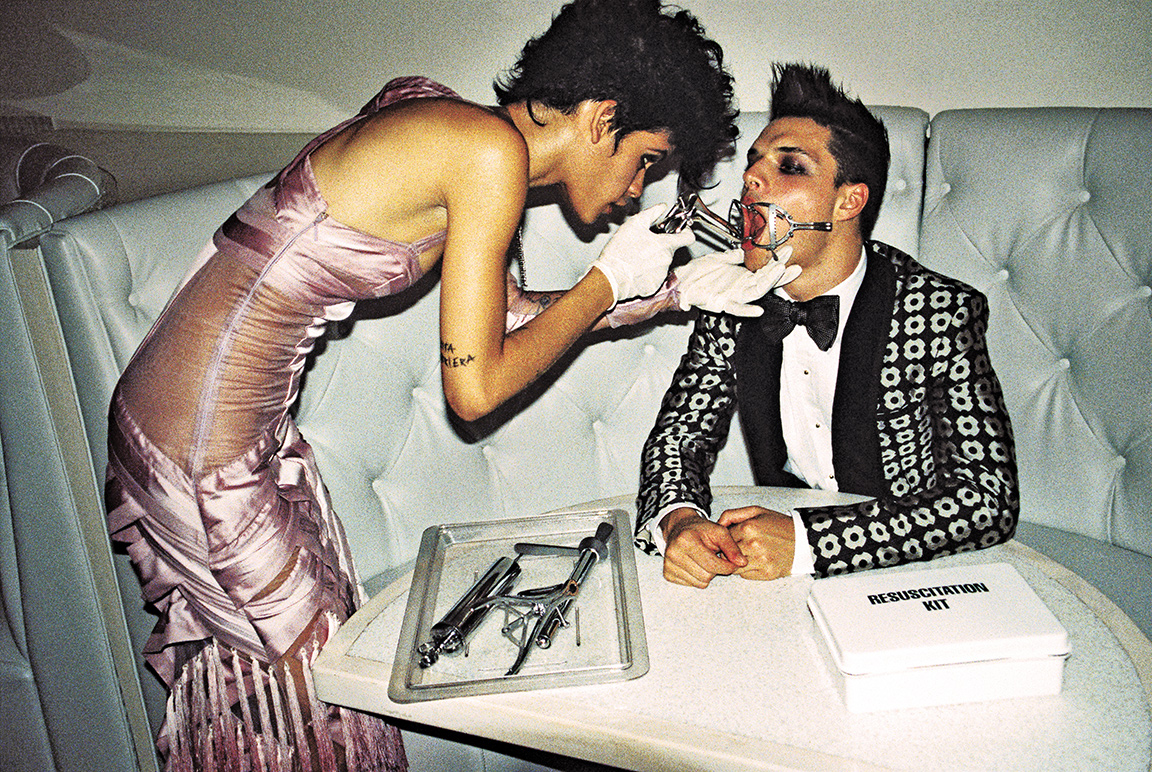

Demystification of all sorts of binaries – especially, but not exclusively, of gender – is central to Mogutin’s visual imagery. This can be seen in one of Mogutin’s very first fashion shoots, for Tom Ford for Gucci (Figure 2).

The figure on the left is dressed in sumptuously feminine attire, described as a ‘silk ribbon one-sleeve dress with organza details and dégradé fringe’. There is an extravagance to the outfit, an extravagance that for Sontag ([1964] 2018: 16) is the very ‘hallmark’ of camp. At the same time, certain physical characteristics of the body wearing the dress – the flat chest, the just-visible Adam’s apple and the soft down covering the forearms – suggest that the figure is in fact a man. Many male transvestites often go to great lengths to ‘pass’ as women. However, as the details I have picked out above suggest, that is certainly not the case here; rather there is a performative element to this man’s excessively camp cross-dressing, something which is reminiscent of drag. Butler observes that drag ‘fully subverts the distinction between inner and outer psychic space and effectively mocks both the expressive mode of gender and the notion of a true gender identity’ ([1990] 2006: 174).

While not wishing to dismiss the possibility of such a reading of this picture, I would nevertheless argue that Mogutin is doing something rather different, but just as subversive, here. There is an exaggerated theatricality, not just about the clothing both models wear but about the composition as a whole. There is an unnaturalness too, conveyed by the postures of both figures, almost as if they were deliberately holding the pose for the camera, and also by the harsh lighting, which projects the standing figure’s shadow against the sofa in the background – not to mention the bizarre contents of the very prominent ‘resuscitation kit’. All of these features make this image a quintessential example of Sontagian camp.

Mogutin is exploiting a camp aesthetic here to challenge the normative representation of gender in much mainstream fashion imagery. In one sense, the Gucci shoot can be seen as a parody of ‘porno-chic’ (see McNair 2013). At the same time, however, Mogutin is also subverting another dominant aesthetic code underpinning the fashion imagery of the time. I refer here to snapshot aesthetics, at the heart of which lies what Schroeder has called, citing Botterill (2007), ‘the snapshot’s insistence upon lived experience, or what has been called “the rhetoric of authenticity”’(2013: n.pag.). As Schroeder demonstrates, Mogutin’s editorial for Gucci came at a time when much photography featured models shot in everyday situations, seemingly caught unawares by the camera – precisely the kind of ‘snapshot aesthetic’ that can be seen in Figure 3. One also thinks of a whole range of western photographers who were working with this aesthetic at the turn of the twenty-first century, such as Richard Billingham, Nan Goldin, Jack Pierson and Juergen Teller (see Cotton 2014), many of whom chose to focus on the male subject. Mogutin subverts that aesthetic in his Gucci shoot, presenting us instead with a picture infused with the unnaturalness, the love of artifice and the exaggeration that Sontag describes, in her very first ‘note’, as the essence of camp.

Figure 5: Slava Mogutin, ‘SUPERM Jockstrap Dawgs’. Artist portfolio for Atlantica (Spain), issue 45, spring 2008 (Mogutin 2021e).

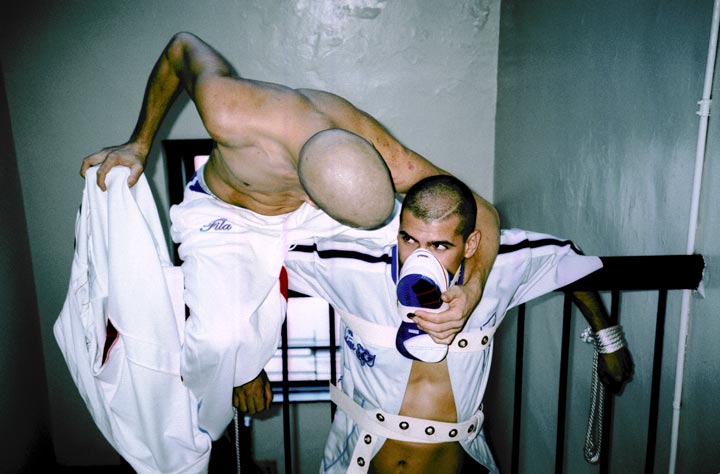

While the portfolio for Tom Ford for Gucci was Mogutin’s first fashion shoot, it is by no means the only example of his camp sensibility from around this time. The very year the Gucci portfolio was published, an exhibition of Mogutin’s photographic work was held at New York’s Rare Gallery, titled No Love. One of the images from that exhibition can be seen in Figure 4. ‘Sneaker Sniffer’, shot in 2003, is one of a number of works by Mogutin that feature men ‘sniffing’ – either sneakers, other men’s armpits or even jockstraps – as in the series ‘Jockstrap Dogs’ (2017: 40–48). As garments, sneakers are loaded with quite specific gendered and sexualized meaning. Kawamura suggests that of all items of clothing, ‘[s]hoes are where gendered identities are most saliently expressed’, adding that sneakers are nothing less than ‘a symbol of manhood’ (2018: 59). Boys and young men may well feel that by walking around in sneakers, they are ‘literally wearing masculinity on their feet’ (Kawamura 2018: 80); as used and sweaty, fetishized, lusted over and at times purloined, sneakers are a stock item of the ‘locker room’ subgenre of gay porn.

What makes the image in Figure 4 so interesting is that it subverts both connotations of the sneaker – that of mainstream masculinity and that of gay porn. This is a BDSM session that wears its strings on its sleeve (almost literally): the belt around the man’s waist is too loose, the rope fastening his wrist to the banister too neatly bound, and, most of all, the sneaker is so immaculate as to look brand spanking new; there is not likely to be anything to ‘sniff’ except perhaps the smell of the soft paper from which it has only just been unwrapped. As a gay BDSM scene, this is just as artificial, just as theatricalized, just as ‘off’ – in other words, just as camp – as Mogutin’s portraits of Katya Zamolodchikova (Figure 1).

One is reminded by Josh and Norbert – and indeed by many other images in No Love – of Sontag’s point about the importance to camp of vulgarity ([1964] 2018: 28, emphasis added): ‘The dandy held a perfumed handkerchief to his nostrils and was liable to swoon; the connoisseur of Camp sniffs the stink and prides himself on his strong nerves’. Josh and Norbert may be ‘connoisseur[s] of Camp’; their vulgarity is patently make-believe – just as much a part of their sham performance of masculinity as their shaven heads (Pilkington 2010). It is, to paraphrase Sontag, ‘exaggerated, [...] fantastic, [...] passionate and [...] naive’ ([1964] 2018: 16). Which is perhaps only to be expected, since, as Sontag herself reminds us,‘[c]amp sees everything in ques- tion marks’ – even ‘vulgarity’ ([1964] 2018: 9). And by its self-consciousness qua vulgarity, Mogutin’s camp sensibility ends up parodying itself.

Much the same is true of the series ‘Jockstrap Dawgs’, shot as part of his SUPERM project. The collage of images from that series can be seen in Figure 5. Here the fetishized object is that other staple of gay porn, the jockstrap. This time, however, it is the image of that fetishized item of male clothing, rather than the fetish itself, that is reproduced ad absurdum. This was a technique that featured in much Soviet avant-garde literature, especially the work of Daniil Kharms and his fellow writers of the Leningrad literary underground of the 1930s – writers whom Mogutin is on record as admiring (Chernetsky 2007: see also Cornwell 1991). Bolton (2019b: I/133)1 suggests, quoting Sontag’s note 46, that it is Andy Warhol who epitomized the Sontagian spirit of camp, since by painting his tins of soup he solved the riddle of ‘how to be a dandy in the age of mass culture’. Yet as a ‘connoisseur of Camp’ (Sontag [1964] 2018: 28), Mogutin surely rivals Warhol; not only does he erase in Figure 5 (and elsewhere) all distinction ‘between the unique object and the mass-produced object’, he provides us with numerous examples of precisely the kind of ‘camp taste [which] transcends the nausea of the replica’ (Sontag [1964] 2018: 27).

Figure 6: Slava Mogutin, ‘BROSEPHINES’. Fashion editorial for Vice (US), volume 18, number 10, October 2011 (Mogutin 2021e).

By the self-consciously theatricalized way in which it is framed, the physical aggression present in Figures 4 and 5 does not buttress hegemonic masculinity, but instead poses a very subversive challenge to that masculinity. Such a challenge is camp in the sense that it shows an ‘off’ vision of a certain kind of ‘reality’ (Sontag’s note 8). Mogutin presents hyperrealized masculinity in outlandish quotation marks, as just another role to be performed – embodied if you will – by the male subject (Sontag’s note 10). If, as Connell (2005) has argued, hegemonic masculinity is deadly serious, Mogutin’s humour of relentless excess and exaggeration triumphs over that seriousness – something which, in her note 41, Sontag suggests is ‘the whole point of Camp’ ([1964] 2018: 26).

In an interview I conducted with Mogutin via video link in March 2021, he claimed: ‘Photography for me is part of a larger project for overturning the phallocratic symbols that exist in the fashion world’ (Mogutin 2021g: n.pag.). This is nowhere more apparent than in the fashion editorial ‘Brosephines’. A number of images from this collection feature male models wearing various recognizably female items of clothing – fishnets, tutus, bralettes, sequined dresses, and so on – while simultaneously clad in items of sportswear generally associated with masculinity, such as American football helmets, or engaging in stereotypically masculine physical activities, like flexing their biceps. One of the best examples is Figure 6, which features a model wearing tight-fitting, brightly coloured briefs and fishnet stockings together with an ice hockey shirt – this last item a visual reference to one of the most violently, hegemonically masculine sports there is (Gee 2009). The multitude of references to bodily contact male sports in the ‘Brosephines’ shoot raises the dual question of taste and pleasure. Mogutin’s models may strut around like peacocks in so many of the pictures here, but through the ‘pleasures’ they indulge in, they are as far removed from the conventional sense of the dandy as it is possible to be. As Sontag ([1964] 2018: 27) notes: ‘The dandy was overbred. [...] The connoisseur of Camp has found more ingenious pleasures. Not in Latin poetry and rare wines and velvet jackets, but in the coarsest, commonest pleasures, in the arts of the masses’.

While there is clearly something ‘off’ about the non-binary way the models in Figure 6 are dressed, the important thing to note is the refusal – characteristic of all the subjects of Mogutin’s camp imagery – to acknowledge this. While for Sontag camp may be the antithesis of tragedy (note 39), it never descends into farce; debunking the serious is itself a very serious business – for, as she puts it in her introduction to the ‘notes’, ‘these are grave matters’ ([1964] 2018: 2). Clad in red stockings and matching suspender belt, the model flexing his biceps in the right-hand side of Figure 6 may well be ridiculing the hyperrealized male body so prevalent in ads for brands from Ralph Lauren and Aussie Bum (Hancock et al. 2014) to Dirk Bikkembergs. While they play around with all kinds of ‘phallocratic symbols’ Mogutin alluded to in my interview, his ‘Brosephine’ models nevertheless keep a very straight face. That is not to say that they exhibit any kind of defiant animosity, however. Rather, there is a complicity, a tenderness in the way the models offer themselves up for what Schroeder (2002) terms ‘visual consumption’. To quote Sontag ([1964] 2018: 33, original emphasis): ‘Camp taste identifies with what it is enjoying. People who share this sensibility are not laughing at the thing they label as“a camp” [sic], they’re enjoying it. Camp is a tender feeling’.

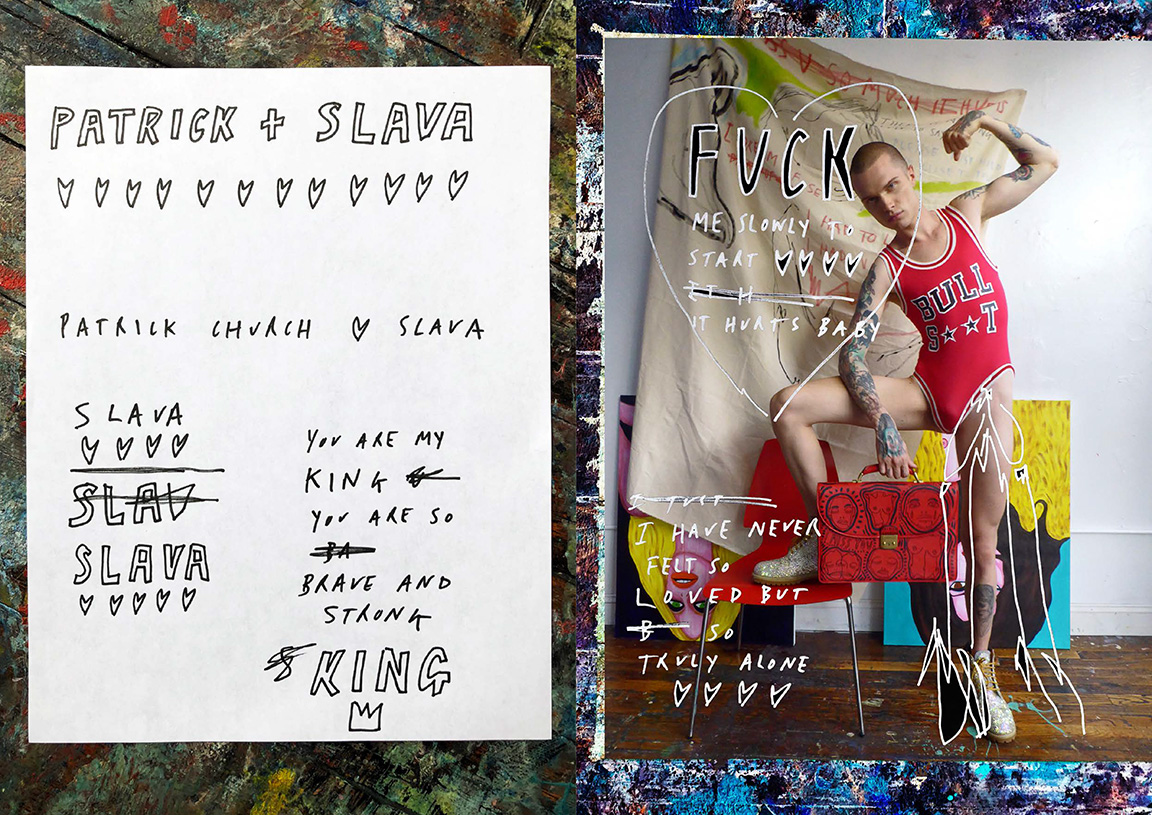

While the models in Figure 6 are anonymous, the subject of Figure 7 is clearly identified. This shot is from a collaborative portfolio Mogutin produced with New York-based contemporary artist Patrick Church. Like many of Mogutin’s ‘Brosephines’, Church also flexes his biceps while gazing tenderly into the camera. There is an echo of the shock value of some of Mogutin’s early work here too, with Church’s invitation to the viewer to ‘fuck me slowly’ writ large in the heart inscribed at the top of the image. What is perhaps most arresting about the image here, however, is the series of tensions it puts on display. These include: romantic love versus carnal desire; image versus text; female versus male clothing, via Church’s epicene body suit. Most importantly, however, Mogutin’s image and the portfolio to which it belongs debunk hegemonic masculinity. This is achieved in Figure 7 by inter alia: Church’s awkward stance; the bored look on his face; the half-hearted, perfunctory flex of the biceps; the customized briefcase, for so long a symbol of hegemonic masculinity’s economic capital; and the faux-innocent naivety of so much of the text – in particular ‘You are my king / You are so brave and strong’ – which with its crossings-out and doodles might almost have been sketched by a bored schoolboy. As Sontag puts it ([1964] 2018: 15): ‘Camp rests on innocence. That means Camp discloses innocence, but also, when it can, corrupts it’.

Much of the Patrick Church collaboration is supremely camp in the Sontagian sense; to paraphrase the text on Church’s body suit, hegemonic masculinity is unmasked here as nothing but ‘bull s**t’. The non-binary, epicene style characteristic of Mogutin’s work with Church is also present in one of his most recent and most aesthetically spectacular fashion shoots, the NIHL S/S 21 ‘Cerberic’ collection for the journal Voyeurs (Figure 8). While the queer dimension of so much of this shoot is certainly interesting, what is perhaps most noteworthy is Mogutin’s use of non-White models here. While the Voyeurs shoot coincided with the rise of the global #BlackLivesMatter movement, this is by no means the first time Mogutin had used BAME models; his first non-White models appeared in a shoot titled ‘Ultraviolets’ for US magazine Flaunt in 2011 (Mogutin 2021e).

As Getsy points out, Mogutin often uses non-White, and especially Black, models to challenge historical White representation of male Blackness,‘turn[ing] his mocking critique to the homoerotic primitivism that is sometimes projected onto [White] representations of black men’ (Getsy 2017: 93). One excellent example of this tendency can be seen in the figure on the right of one of the double-page spreads in Voyeurs 2.0 (Figure 8). Seated rigidly, regally, against a sylvan backdrop, this figure gazes impassively out at us from beneath his short dark hair shaped rather like a crown. Is that an orb on his knee, and are they the shrunken heads of his defeated foes slung around his neck? As if to underline the need for deference in this man’s presence, the shot is taken at eye level, inviting the viewer physically to bend forward. As we do so, our gaze is immediately drawn to the long phallic-like object snaking out menacingly from between his legs. This impression – this representation – is self-parodic, however: the orb looks no stronger than a helium balloon, the ‘throne’ is little more than an overturned plastic bottle crate, those ‘shrunken heads’ cover his nipples like a bra, this ‘king’ is wearing heels, and as for the pink cuddly toy masquerading as a snake... And yet there he sits, staring back out at us as straight-faced as any real monarch. Grave matters indeed.

Figure 7: Slava Mogutin. Collaborative cover portfolio with Patrick Church, Ansinth Magazine, issue 2, FW 2018/19 (Mogutin 2021f).

CONCLUSION

Every time I do a show or have an opportunity to publish my work, I feel like a queer insurgent. Coming from such a conservative and homophobic place, I don’t take any freedoms or liberties for granted. I also feel like I paid my dues for the right to address the injustices and evils of Trump’s politics. I spent half of my life in the US, so I feel equally Russian and American now. I believe in building bridges not walls.

(Camblin 2019: n.pag.)

As a queer insurgent, Mogutin brings his very own brand of camp sensibility to attack three targets in particular: institutionalized homophobia in his native Russia; online censorship; and the hegemonic, hyperrealized masculinity on display in much western fashion advertising and western media. While Mogutin claims to have been heavily influenced by Soviet avant-garde artists such as Vladimir Mayakovsky and Aleksandr Rodchenko, there is nevertheless something ‘global’ about Mogutin’s style. He is a ‘camp antagonist’ who, to paraphrase Galvin’s comment on Leigh Bowery, ‘defies normative culture by creating and performing provocative“looks”that [are] full of contradictions and tensions, to the point that oppositions [stand] as a new hybrid form of oxymoron’(Galvin 2020: 187).

Mogutin’s ‘camp antagonism’ can be found throughout much of contemporary men’s fashion, from brands such as Palomo Spain to fashion magazines such as Pansy in the United States (McCauley Bowstead 2018). Moreover, as a sensibility that links very different aesthetic traditions and codes, that antagonism is noteworthy for the challenge it poses for the research agenda on camp. This challenge lies in two areas in particular. First, there is the need to redress the balance away from North America and Western Europe to examine the different forms camp might take elsewhere. Where Russia is concerned, Mogutin stated in 2000:

I absolutely do not feel that I have anything in common either with this language or this culture or these people or this place or this time but due to someone’s cruel irony or to someone’s fucking me up I continue to be called a russian [sic] poet.

(Chernetsky 2007: 180)

And yet in his ‘Artist statement’, he claims: ‘Informed by my dissident and refugee background, my work has as much to do with a personal point of view as with social commentary and political activism. For me, the personal is political and the political is personal’ (Mogutin 2021d: n.pag.). To make such an assertion an integral part of his artistic manifesto reflects a belief in the artist’s mission salvatrice – a belief that is characteristically Russian. It was a sentiment particularly close to the hearts of the Soviet artistic avant-garde, not just Mayakovsky and Rodchenko but countless others too, such as the Constructivists Varvara Stepanova and Lyubov Popova, or the artists Aleksandr Deineka and Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, all of whom believed in Revolution-through-Art (see, e.g., Kiaer 2005; Tupitsyn 2009; Roberts 2019; Mogutin 2021d). This is surely why, during my interview with him, Mogutin cited the Russian avant-garde of the 1920s and 1930s as the most important influence on his work (Mogutin 2021g). This may also lie behind his claim made during that same interview to be a Russian patriot and to take a keen interest in Russian religious philosophy.

Mention of the Russian avant-garde, and the revolutionary fervour of so many of its members, brings me to my second point. It is surely time to bring Sontag’s understanding of camp out of the closeted early 1960s and into the twenty-first century. More specifically, it is the challenge it poses to the way you or I might see the world that makes camp so political – despite Sontag’s insistence on the ‘apolitical’ nature of camp sensibility ([1964] 2018: 5; on the politics of camp, see, e.g., Meyer 1994; Horn 2017; Hitchcock and McCauley Bowstead 2020). As we have seen, the targets of Mogutin’s camp sensibility, and indeed the channels via which he reaches those targets, evolve overtime. This in turn implies two things: first, that as a sensibility, camp inevi- tably emerges in a specific political context – ‘the canon of Camp can change’ (Sontag [1964] 2018: 19); and second, far from being unintentional as Sontag maintains, the camp aesthetic may, on the contrary, be part of a conscious and quite deliberate desire to subvert the sexual status quo. In my interview with him, Mogutin claimed to use fashion primarily ‘as a platform for pushing gender boundaries’ (Mogutin 2021g: n.pag.). If, as Sontag claims ([1964] 2018: 25), ‘[c]amp and tragedy are antitheses’, then Mogutin’s queer insurgency may well be destined for a happy end.

Figure 8: Slava Mogutin. NIHL S/S 21 ‘Cerberic’ collection, Voyeurs Journal, fall 2020, #2 (Mogutin 2021f).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to thank Charles Athill of the London College of Fashion for his many helpful comments on an earlier version of this article, and also Dr Sarah Gilligan of Northumbria University for bringing to his attention the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exhibition Camp: Notes on Fashion.

REFERENCES

Anon. (2019), ‘Slava uncensored’, Office Magazine, 12 March, http://office magazine.net/slava-uncensored. Accessed 3 February 2021.

Arte (2017),‘Slava Mogutin, le Rimbaud russe (2014)’, Youtube, 18 September, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fStE0pWpW1o. Accessed 3 February 2021.

Barry, Ben and Phillips, Barbara (2016), ‘Destabilizing the gaze towards male fashion models: Expanding men’s gender and sexuality identities’, Critical Studies in Men’s Fashion, 3:1, pp. 17–35, https://doi.org/10.1386/ csmf.3.1.17_1. Accessed 17 September 2021.

Bolton, Andrew (ed.) (2019a), Camp: Notes on Fashion, New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press/Metropolitan Museum of Art New York.

Bolton, Andrew (2019b), ‘Sontagian camp’, in A. Bolton (ed.), Camp: Notes on Fashion, New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press/MetropolitanMuseum of Art New York, pp. I/129–33.

Booth, Mark (1983), Camp, London: Quartet.

Bordo, Susan (1999), The Male Body: A New Look at Men in Public and in Private, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Botterill, Jacqueline (2007), ‘Cowboys, outlaws, and artists: The rhetoric of authenticity and contemporary jeans and sneaker advertisements’, Journal of Consumer Culture, 7:1, pp. 105–25, https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540507073510. Accessed 17 September 2021.

Brajato, Nicola and Dhoest, Alexander (2020), ‘Practices of resistance: The Antwerp fashion scene and Walter Van Beirendonck’s subversion of masculinity’, Critical Studies in Men’s Fashion, 7:1&2, pp. 51–72, https://doi. org/10.1386/csmf_00017_1. Accessed 17 September 2021.

Bronski, Michael (1984), Culture Clash: The Making of Gay Sensibility, Boston, MA: South End Press.

Butler, Judith ([1990] 2006), Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, London and New York: Routledge.

Camblin, Victoria (2019), ‘“Like a queer insurgent”: Slava Mogutin’s XXX files’, 032c Magazine, 2 January, https://032c.com/like-a-queer-insurgent. Accessed 8 February 2021.

Chernetsky, Vitaly (2007), Mapping Postcommunist Cultures: Russia and Ukraine in the Context of Globalization, Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Cleto, Fabio (2019), ‘The spectacles of camp’, in A. Bolton (ed.), Camp: Notes on Fashion, New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press/Metropolitan Museum of Art New York, pp. I/9–59.

Cole, Shaun (2013), ‘Queerly visible: Gay men, dress, and style 1960–2012’, in V. Steele (ed.), A Queer History of Fashion: From the Closet to the Catwalk, New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press/Fashion Institute of Technology New York, pp. 135–65.

Cole, Shaun (2015), ‘Looking queer? Gay men’s negotiations between masculinity and femininity in style and dress in the twenty-first century’, Clothing Cultures, 2:2, pp. 193–208, https://doi.org/10.1386/cc.2.2.193_1. Accessed 17 September 2021.

Connell, R. W. (2005), Masculinities, 2nd ed., Cambridge: Polity.

Cordero, Robert (2019), ‘The business of casting queer models’, Business of Fashion, 14 October, https://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/news-analysis/the-business-of-casting-queer-models. Accessed 3 February2021.

Cornwell, Neil (ed.) (1991), Daniil Kharms and the Poetics of the Absurd: Essaysand Materials, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cotton, Charlotte (2014), The Photograph as Contemporary Art, 3rd ed., London: Thames and Hudson.

Dams, Jimi ([2013] 2021), ‘Slava Mogutin. Introduction for artist portfolio in Eyemazing Magazine, winter 2013’, https://slavamogutin.com/jimi-dams/. Accessed 10 February 2021.

Edwards, Tim (2006), Cultures of Masculinity, Abingdon and New York: Routledge.

Erlich, Victor (1994), Modernism and Revolution: Russian Literature in Transition, Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press.

Essig, Laurie (1999), Queer in Russia: A Story of Sex, Self, and the Other, Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press.

Fedorova, Anastasiia (2013), ‘Slava’s homoerotic protest photography’, Dazed, 15 August, https://www.dazeddigital.com/photography/article/16896/1/slavas-homoerotic-protest-photography. Accessed 9 February 2021.

Galvin, Kirsten (2017), ‘Anatomy’s a drag: Queer fashion and camp performances in Leigh Bowery’s Birth Scenes’, Critical Studies in Men’s Fashion, 4:2, pp. 185–202, Accessed 17 September 2021.

Geczy, Adam and Karaminas, Vicki (2013), Queer Style, London and New York: Bloomsbury.

Geczy, Adam and Karaminas, Vicki (2016), Fashion’s Double: Representations of Fashion in Painting, Photography and Film, London and New York: Bloomsbury.

Geczy, Adam and Karaminas, Vicki (2017), Critical Fashion Practice: From Westwood to Van Beirendonck, London and New York: Bloomsbury.

Gee, Sarah (2009), ‘Mediating sport, myth, and masculinity: The national hockey league’s “inside the warrior” advertising campaign’, Sociology of Sport Journal, 26, pp. 578–98, https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.26.4.578. Accessed17 September 2021.

Getsy, David J. (2017), ‘Slava Mogutin, Infiltrator’, in S. Mogutin (ed.), Bros & Brosephines, Brooklyn, NY: PowerHouse Books, pp. 91–95.

Gutierrez, Benjamin (2017), Slava Mogutin: “I transgress, therefore I am”, Document Journal, 1 August, https://www.documentjournal.com/2017/08/slava-mogutin-i-transgress-therefore-i-am/. Accessed 2 February 2021.

Hancock II, Joseph H. and Karaminas, Vicki (2014), ‘The joy of pecs: Representations of masculinities in fashion brand advertising’, Clothing Cultures, 1:3, pp. 269–88, https://doi.org/10.1386/cc.1.3.269_1. Accessed 17 September 2021.

Hitchcock, Fenella and McCauley Bowstead, Jay (2020), ‘Queer fashion and the camp tactics of Charles Jeffrey LOVERBOY’, Critical Studies in Men’s Fashion, 7:1&2, pp. 27–49, https://doi.org/10.1386/csmf_00016_1. Accessed 17 September 2021.

Horn, Katrin (2017), Women, Camp and Popular Culture: Serious Excess, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Katz, Jonathan D. (2013), ‘Queer activist fashion’, in V. Steele (ed.), A Queer History of Fashion: From the Closet to the Catwalk, New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press/Fashion Institute of Technology New York, pp. 219–32.

Kawamura, Yuniya (2018), Sneakers: Fashion, Gender, and Subculture, London and New York: Bloomsbury Visual Arts.

Kayvon, Shervin (2017), ‘Art through activism: A chat with artist Slava Mogutin’, Impact, 20 March, https://www.intomore.com/impact/a-chat-with-artist-slava-mogutin/. Accessed 2 February 2021.

Kiaer, Christina (2005), Imagine No Possessions: The Socialist Objects of Russian Constructivism, Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press.

LaBruce, Bruce (2017), ‘[untitled]’, in S. Mogutin (ed.), Bros & Brosephines, Brooklyn, NY: PowerHouse Books, p. 177.

LaBruce, Bruce ([2009] 2021), ‘Pinko commie fag: Interview with Slava Mogutin for East Village Boys, September 2009’, https://slavamogutin.com/bruce-labruce/. Accessed 8 February 2021.

LaBruce, Bruce and Mogutin, Slava ([2016–17] 2021), ‘Some roughs are really queer, some queers are really rough. Bruce LaBruce and Slava Mogutin in conversation with Ben Reardon’, https://slavamogutin.com/slava_blab_ man_about_town/. Accessed 8 February 2021.

Lord, Catherine (2019), ‘Inside the body politic: 1980–present’, in C. Lord and R. Meyer (eds), Art and Queer Culture, 2nd ed., London and New York: Phaidon, pp. 27–46.

LVL3 (2015), ‘Spotlight: Slava Mogutin’, 1 June, https://lvl3official.com/ spotlight-slava-mogutin/. Accessed 8 February 2021.

Malbon, Ben (1999), Clubbing: Dancing, Ecstasy and Vitality, London and New York: Routledge.

Malley, Claire (2019), ‘Slava Mogutin’s very queer, very NSFW response to online censorship’, Document Journal, 10 January, https://www.document journal.com/2019/01/slava-mogutins-very-queer-very-nsfw-response-to- online-censorship/. Accessed 2 February 2021.

Marcadé, Jean-Claude (2008), ‘Slava Mogutin – poète, critique, photographe – mise en scène du corps’, in B. Dhooge, T. Langerak and E. Metz (eds), Provocation and Extravagance in Modern Russian Literature and Culture, Amsterdam: Pegasus, pp. 141–62.

McCauley Bowstead, Jay (2018), Menswear Revolution: The Transformation of Contemporary Men’s Fashion, London and New York: Bloomsbury.

McNair, Brian (2013), Porno? Chic! How Pornography Changed the World and Made It a Better Place, Abingdon and New York: Routledge.

Meyer, Moe (ed.) (1994), The Politics and Poetics of Camp, London and New York: Routledge.

Mogutin, Slava (2006), Lost Boys, Brooklyn, NY: PowerHouse Books.

Mogutin, Slava (2015), Moon River (Uncut), Vimeo, https://vimeo.com/162268834. Accessed 6 February 2021.

Mogutin, Slava (2017), Bros & Brosephines, Brooklyn, NY: PowerHouse Books.

Mogutin, Slava ([2016] 2017), ‘The censorship monster: Who’s afraid of a queer nipple in the digital age? (an open letter to Mr. Mark Zuckerberg)’, Huffington Post, 6 December, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/the-censorship-monster- wh_b_11308324?. Accessed 15 February 2021.

Mogutin, Slava ([2004] 2021), ‘No Love’, https://slavamogutin.com/no-love/. Accessed 10 February 2021.

Mogutin, Slava ([2006] 2021),‘Lost Boys’, https://slavamogutin.com/lost-boys/. Accessed 10 February 2021.

Mogutin, Slava ([2016–17] 2021), ‘I’m Your Man’, http://slavamogutin.com/man-about-town/. Accessed 1 February 2021.

Mogutin, Slava (2021a), ‘Narrative biography’, https://slavamogutin.com/bio/. Accessed 11 February 2021.

Mogutin, Slava (2021b), ‘Videos’, https://slavamogutin.com/videos/. Accessed 6 February 2021.

Mogutin, Slava (2021c), ‘Press archive’, https://slavamogutin.com/press-archive/. Accessed 6 February 2021.

Mogutin, Slava (2021d), ‘My Existence = My Resistance. Artist statement’, https://slavamogutin.com/artist-statement/. Accessed 8 February 2021.

Mogutin, Slava (2021e), ‘Magazine projects’, https://slavamogutin.com/magazine-projects/. Accessed 10 February 2021.

Mogutin, Slava (2021f), ‘Magazine projects NEW’, https://slavamogutin.com/magazine-projects-new/. Accessed 11 February 2021.

Mogutin, Slava (2021g), online interview with G. H. Roberts, 9 March 2021.

Pilkington, Hilary (2010), ‘No longer “on parade”: Style and performance of skinhead in the Russian far north’, Russian Review, 69:2, pp. 187–209, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25677193. Accessed 17 September 2021.

Roberts, Graham H. (2019), ‘Queering the stitch: Fashion, masculinity and the post-socialist subject’, Critical Studies in Men’s Fashion, 6:1&2, pp. 59–80,https://doi.org/10.1386/csmf_00005_1. Accessed 17 September 2021.

Rosen, Miss (2017), ‘Why Slava Mogutin is Russia’s greatest art rebel’, Dazed, 24 July, https://www.dazeddigital.com/art-photography/article/36845/1/why-slava-mogutin-is-russias-greatest-art-rebel-bros-and-brosephines. Accessed 27 January 2021.

Sando, Cee (2020), ‘Janaya “Future” Khan: At the intersection of activism and fashion’, Qwear, 29 February, https://www.qwearfashion.com/home/janaya-future-khan-at-the-intersection-of-activism-and-fashion. Accessed 9 February 2021.

Sawdon Smith, Richard (2020), ‘The unknowing ... X: Queering representations of masculinity in an undetectable world’, Critical Studies in Men’s Fashion, 7:1&2, pp. 223–27, https://doi.org/10.1386/csmf_00026_7. Accessed 17 September 2021.

Schroeder, Jonathan E. (2002), Visual Consumption, Abingdon and New York: Routledge.

Schroeder, Jonathan (2013), ‘Snapshot aesthetics and the strategic imagination’, InVisible Culture, 18, 10 April, https://ivc.lib.rochester.edu/snapshot-aesthetics-and-the-strategic-imagination/. Accessed 10 February 2021.

Sontag, Susan ([1964] 2018), Notes on ‘Camp’, Harmondsworth: Penguin. Steele, Gabriel (2020), ‘Man-made man: The role of the fashion photograph in the development of masculinity’, Critical Studies in Men’s Fashion, 7:1&2, pp. 5–20, https://doi.org/10.1386/csmf_00014_1. Accessed 17 September2021.

Steele, Valerie (ed.) (2013), A Queer History of Fashion: From the Closet to the Catwalk, New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press/Fashion Institute of Technology New York.

Tupitsyn, Margarita (2009), ‘Being-in-production: The constructivist code’, in M. Tupitsyn (ed.), Rodchenko and Popova: Defining Constructivism, London: Tate Publishing, pp. 13–30.

Vainshtein, Olga (2019), ‘Fashioning the “performance man”: Costumes andcontexts of Andrey Batrenev’, Critical Studies in Men’s Fashion, 6:1&2, pp. 13–36, https://doi.org/10/1386/csmf_00003_1. Accessed 17 September 2021.

© Roberts, Graham H. (2021),‘Queer Insurgency: Slava Mogutin and the Politics of Camp’, Critical Studies in Men’s Fashion, 8:1&2, pp. 141–61, https://doi. org/10.1386/csmf_00037_1