The Legend of Marina Abramović

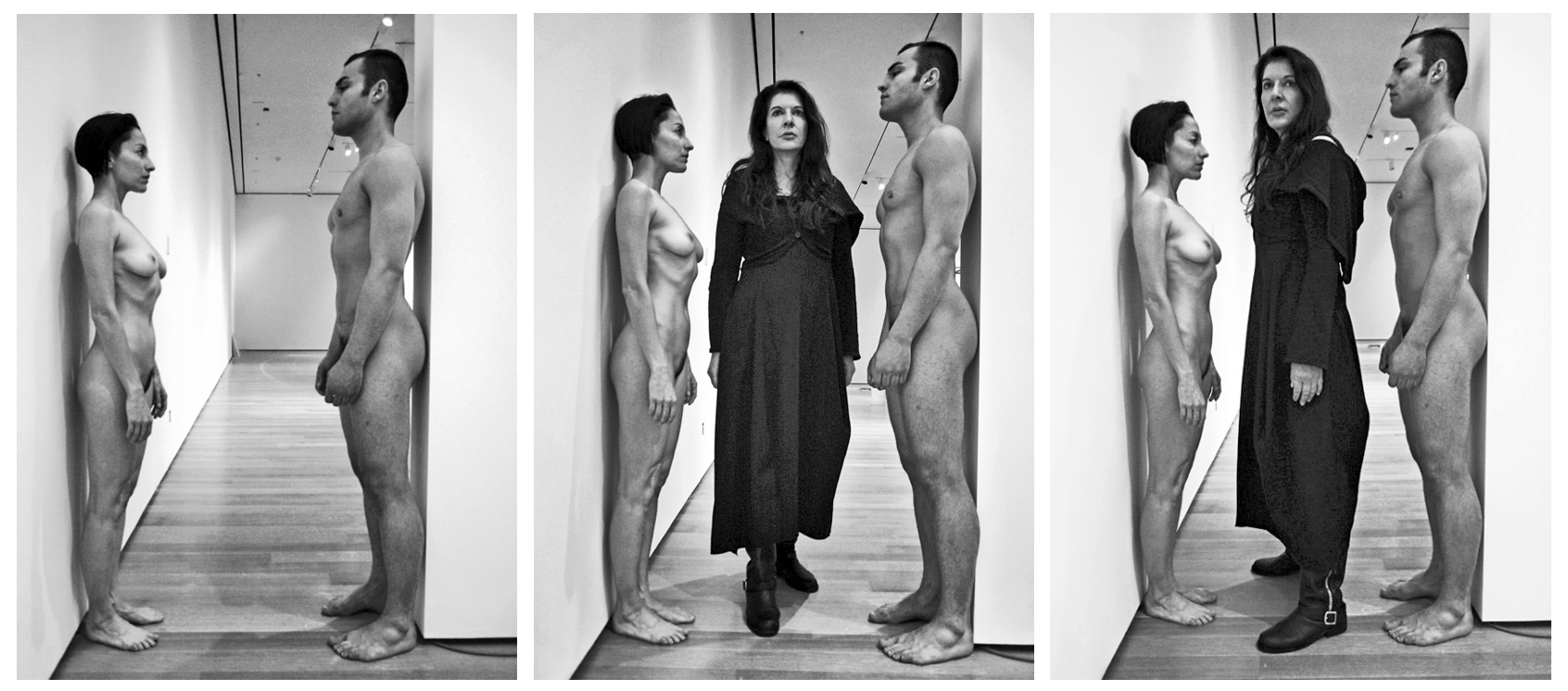

When her 23-year collaboration with Ulay ended, Marina continued solo and, against all odds, became the most celebrated female performance artist, responsible for making performance an institutionalized art form. In the process, she sealed her reputation as the self-proclaimed “grandmother of performance art” (a term that Marina now rejects) and the icon — or brand — for a whole new generation of performance artists. The most resilient of them found themselves lucky enough to be able to reenact, or re-perform, the best of Marina’s 40-year-long repertoire at her recent retrospective “The Artist Is Present” at the Museum of Modern Art. The artist was present, indeed — wearing a long dress and sitting in blinding lights, motionless and speechless, for three months during museum hours, or seven hundred hours — setting the record for the longest-durational art performance and being a living monument to herself. It was by far the most alive show that I’ve ever seen at MoMA, bursting with energy and emotion. Some visitors simply couldn’t contain themselves and were kicked out for grabbing nude models.

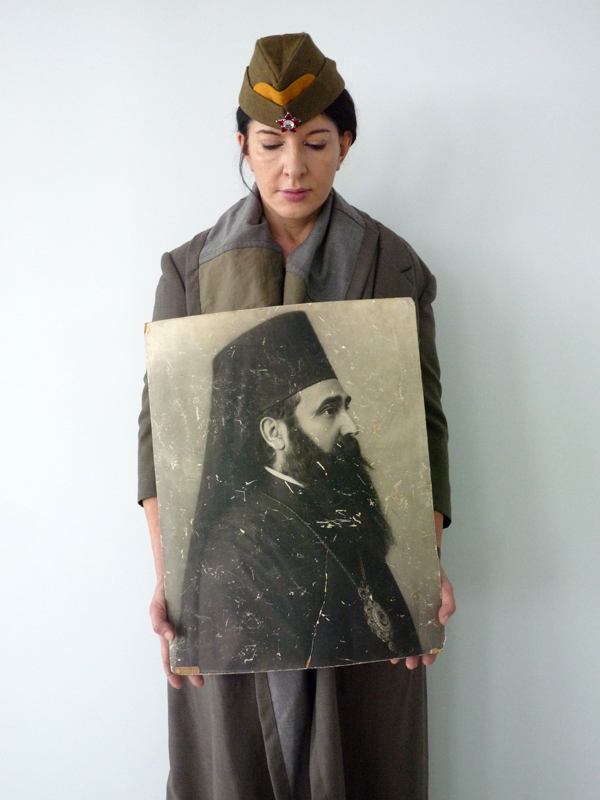

I interviewed and photographed Marina at her new home, a spacious designer loft in SoHo, while she was preparing for her MoMA marathon. A compelling and convincing storyteller, Marina practically interviewed herself, showing books, pictures, and memorabilia from her native Serbia and far beyond. It was hard to imagine how someone who has so much to say and who’s so full of life could also sit still and mute for so long.

Slava Mogutin: You call yourself the Grandmother of Performance Art...

Marina Abramović: And actually I very much regret saying that, because now everyone quotes it and nothing else!

SM: There’s no way of going back now. It’s already written in stone!

MA: I hate to be called a grandmother, not because of my age, but because what I really meant was that I was a pioneer. Now I prefer to call myself a pioneer of performance art.

SM: Well, here’s the second part of my question: Who’s your daddy?

MA: Who is my daddy? I feel more like an orphan. The daddy’s unknown — who knows what the mother was doing when she was young? I never really looked at other artists as an inspiration, because artists are always influenced by someone else, so why should I be influenced secondhand? I looked at different people, like shamans, and I was very influenced by theosophy and Buddhism. So who can be my daddy? I’d like to think of Gurdjieff as my daddy. Gurdjieff mixed with volcano.

SM: Volcano?

MA: Yeah, I love volcanoes. I like all that exploding energy, which makes us think about mortality and somehow gives us a connection to the planet as a living being.

SM: I know that you had a very strict, militant kind of upbringing, which affected both your life and your practice. You mentioned that you even have your food in the fridge organized in a very militant way.

MA: Totally, and I’m trying to put all my clothes in line now because it’s a mess here. Normally it’s very organized. But now I’m creating a military camp before my performance at MoMA.

SM: I read that your mother used to control your life to the point that she put you under a strict curfew, so you had to be back home no later than 10 p.m., no matter what kind of radical or life-threatening performances you did. Was it a masochistic part of you — the need for this kind of discipline that you submitted yourself to?

MA: So many people ask me, “You were doing all those crazy things and pushing limits in many ways, why couldn’t you rebel against your own mother?” But this is the contradiction: I really couldn’t rebel against her, because I was really afraid of her. She was literally ruling my life. This is why I became such an antifeminist. It was very strange, the kind of fear I had about her, to the point that I really never rebelled. And one day I said, “Okay, now it’s enough!” and I left. But, you see, the whole social structure in Belgrade was entirely different from the West. You just couldn’t go and live by yourself. It was impossible because there were no apartments. It was all socialism-communism . . .

SM: I can relate to that because it was quite similar in the Soviet Union. Even in today’s Russia many people are forced to live with their parents and grandparents.

MA: And you have layers and layers of family members living with you, grandmothers and grandfathers, different generations with their own set of rules. You feel really claustrophobic, but there’s nothing you can do against this ancient system, it’s unchangeable. I could rebel against everything, but by 10 o’clock I had to be back home.

SM: Was it somehow reflected in your early performances?

MA: I was rebelling against the family, but also against the society and the entire education system of the art academy. To the point that my parents were questioned at the Communist Party meetings whether I could continue doing this stuff publicly. My professor of art was saying that what I was doing was nonsense, that I deserted art and should be put in a mental hospital!

SM: I was wondering how you got away with being as nonconformist as you were in the communist environment.

MA: Our student culture center was a little isolated island, separate from the rest of the country. It was actually right in front of the headquarters of the secret police, but we had a little bit of freedom, just because the director of the center was a daughter of one of the ministers. Back in the sixties, it used be a social club, where the wives of communist officials would meet and gossip while their husbands played chess. Then, in 1968, the students held demonstrations and demanded better food, social and cultural changes, bigger grants, and so on, and we asked for this place to be given to the students as our culture center. From the thirty points of our demands Tito actually answered only six, and one of the six points was to give us this house, where we could do all these experimental things. Nobody touched us, but nobody cared about us either. We didn’t matter on the large scale and didn’t really change anything in the cultural background of Belgrade. That was the situation, a kind of strange isolation in that context. There were six of us — I was the only girl, and five guys. We would leave our homes in the morning, stay at the center all day long, and try to make our work.

SM: So, in a way, you were tolerated, but you weren’t a part of the officially recognized structure or art movement.

MA: Exactly, we weren’t a part of anything. I worked that way for five years and then I left Yugoslavia. I ran away, and my mother went to the police to report that I escaped from the house. They asked, “What is her age?” She said, “29,” and they said, “This is about time! ” It was ridiculous, but it was my real situation. But then my problem became even bigger. Because I come from a country where everything was forbidden. You knew that for a bad political joke you would get two years of prison, and for a really bad joke you would get four, so all the rules were clear. So I come to Amsterdam, it was in the middle of the seventies, where everything was okay . . .

SM: The polar opposite of the Communist society.

MA: Totally opposite! Nobody cared, you could be dressed or naked, you could take drugs or do whatever—total freedom! I had a huge problem with that. I could no longer function, because somehow my whole world didn’t mean anything anymore.

SM: Your whole system has collapsed.

MA: Yes, completely! And it wasn’t just my problem but the problem of so many artists coming from East Europe—somehow their work in the West didn’t really function anymore. Their position was much stronger when they were back home, like Djilas, one of the main opposition leaders to Tito. He spent 55 years in prison, and when Tito offered him his passport so he could leave the country, he said, “I have no desire to leave. I’d rather stay in prison in my country because then I have the power!” So when I left, it was a really difficult time for me. I had to invent the entire new set of rules for myself in order to bring my work into function.

SM: How did you manage to escape from Yugoslavia? I guess, it wasn’t as easy to travel abroad back then…

MA: It was very easy during Tito time, much easier than now. We could travel but the problem was we didn’t have any money.

SM: I guess, it was different in Yugoslavia because it wasn’t like the rest of the Communist block. It was somewhat liberal, right?

MA: We had much more freedom. In relation to Russia, Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania, we were like the West. We even had our own Playboy! I remember, the first time we got Playboy, it was like revolution! And I remember looking for the centerfold, where you were supposed to see the girl of the year… You know what it was in our Playboy? It was a brand-new bright-red tractor, with no girl!

SM: Fantastic! It was like some sort of conceptual porn.

MA: Nobody believes me, but I still have that picture somewhere. And they thought this was the most erotic thing you could ever imagine—red tractor with no girl, the highest sexual desire of that communist rural country! When you understand the humor of it, then you’ll understand me.

SM: But at the same time you had some very radical and interesting filmmakers like Dushan Makaveev and Emir Kusturica, whom I absolutely love.

MA: And that’s why Yugoslavia was such a cradle of freedom. We had some incredibly talented people like Dushan Makaveev, who made “Mysteries of the Organism,” which was a total cult movie, and still is. He also organized the first international porn festival, where they screened erotic movies all night long. Back in the early 70’s, Yugoslavia was a volcano of creative energy, but the art was really socialist. Every important art person or curator from abroad who visited Yugoslavia would first be brought to the Museum of Art and Revolution, where my mother was the director. That was the official place to visit, which I hated and rebelled against. And our culture center was never being shown in any of the official visits. It didn’t exist in a way.

SM: And then you met Ulay and started collaborating. Was it that new structure that you were missing after you left Yugoslavia?

MA: No, it wasn’t about the structure, it was something else. My work was becoming more and more radical, and I was risking more and more. In a way, it looked like I was seeking my own death and I would eventually die during one of my performances. That’s how crazy and rebellious I was about everything. I got an invitation to come to Amsterdam exactly on my birthday. And my grandmother, who actually knew nothing about my work, said, “Everything that happens on your birthday is important — it’s destiny.” She just told me that. So I arrive on my birthday, 13th of November, to record a television program on body arts. And there I meet Ulay, who’s invited to be a part of the same program with his own performance. And when I met him, half of his face was shaven and with short hair and the other half had complete makeup and long hair. So he was a man and a woman at the same time. I got really fascinated! When we finished shooting, I said to everybody, “I’d like to offer you a drink because it’s my birthday.” And Ulay stands up and says, “I would also like to offer a drink, it’s my birthday!” So I said, “I don’t trust you, prove it!” He didn’t have anything to prove, but he showed me his diary and the page with the date 13th of November was ripped off. “See, this is my proof!” I couldn’t believe it, because every time I buy a diary, the first thing I do, I rip off the page with the date of my birthday. Every diary I’ve ever had. And that same evening they put our hair together with chopsticks, which was our first performance together. So this was such an incredible omen, performing live the same night! When I went back to Belgrade, I stayed in bed for 10 days because I was lovesick. Then I made so many phone calls to Ulay that my mother blocked the phone line. We decided to meet exactly in the geographical middle, between Amsterdam and Belgrade, which was Prague, Czechoslovakia. So he took KLM and I took Aeroflot, and my Aeroflot flight was eight hours late, so he was waiting for me . . .

SM: When I was watching the documentation of your early collaborative work, there’s something very innocent and naive about it. In retrospect it seems a bit like the offspring of the hippie revolution, the liberation of the body and back-to-nature movement. Especially given the time and the place where you met and the whole new settings.

MA: It’s so funny, when I came to Amsterdam I didn’t even know of the Rolling Stones. Because of my education in Belgrade, I had no idea about contemporary music. I was listening to Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven and was going to see the Bolshoi Theatre. And Ulay was living in nightclubs and cleaning his teeth with Courvoisier whiskey. And the drugs — that was another wall between us. I never had a joint in my life, never smoked. I was so out of that world, even by the Yugoslav standards, because of my mother’s military control. I was the most straight-laced person in Amsterdam. So as soon as I could, I took Ulay out of this. After six months he left his place, he left everything, and we bought this Citroën bus and went traveling around Europe and lived in the most radical and minimal way. He quit smoking and drinking; we were drinking only water. And when you look back — yes, maybe it looks like we were hippies, but we were incredibly organized and disciplined with every single work we did.

SM: So you had a fixed laundry day, no matter where you were?

MA: Oh, totally! Everything was ritualized in a certain way. At that moment, in the end of the seventies, when everyone wanted to go back to objects and paintings and people just stopped doing performances, we didn’t want to, we found performance to be the most transformative life form of art there is. So we went back to nature, we went to desert and then spent one year living with the aborigines. When we came back, our art was somewhere else, but we never stopped doing it. So it was like you take the hippie thing but translate it into a radical drill training that was required in order to make this kind of performances, pieces of 16 hours or more. We needed an incredible amount of concentration and willpower to do that. Our life and art were really close.

SM: So what happened between the two of you? Why did you and Ulay go separate ways?

MA: In a way, it was very simple. It was difficult for the public to see two people as one piece of art. We didn’t want to tell who the idea was coming from, because we mixed our ideas together. We created this mythical couple, but, still, people saw that I was stronger. He really started suffering from that and the more he suffered, the more he tried to punish me in private life. Then started being unfaithful. He couldn’t take the tension of being a part of that ideal couple. In the end, for the last three years I couldn’t admit that everything was falling apart; I couldn’t admit that our relationship wasn’t working. I tried everything, but then finally I had to accept that it was over.

SM: I watched the documentation of your last performance with Ulay walking the Great Chinese Wall and it’s very melodramatic. It seems bittersweet.

MA: Before we walked the Chinese Wall we couldn’t perform anymore. We built two vases, The Sun and The Moon. One vase absorbs the light and the other reflects the light and they’re exactly the size of our bodies. This was the ability to actually continue. We became objects. And then we went to China and walked the Great Wall for 2,500 kilometers from the opposite sides to say goodbye when we met in the middle. Somebody told us, “Are you insane? You can just split and that’s it! Why do you have to walk for such a long time just to take different directions?” When we started our relationship, Ulay was doing much more photography and I was doing performance. So each of us had a different suitcase, his was photography and mine was performance. We mixed everything together and were doing performance, photography and video. Then when we split, he continued with photography and I continued more with performance.

SM: What about your multimedia work—photography, video, objects, sculptures?

MA: I never made sculptures, I call them transitory objects, so the public can interact and experience doing the work. Sculpture is something permanent, I prefer more transitory. Every media requires a different concept, like with the video: sometimes I direct a movie, sometimes I play in it. The MoMA exhibition is very radical, it’s not about all my work, it’s only about performances where I’m present, where Ulay is present, where other artists are present. But it doesn’t show sculptures, the transitory objects, it doesn’t show photography or video that I’ve directed. It’s only about one particular aspect of performance.

SM: Can you describe the actual process of creating a performance?

MA: It’s hell. I start with hell. When I get an idea and I like it, I kind of don’t bother with it. But if a certain idea comes as a surprise and I get shocked, I say, “Oh, God, this is crazy!” Then I get really scared of it. Then that idea starts nagging and I get totally obsessed with it. I get so obsessed that I really look forward to making it into a performance. I’m so jealous of those great artists that can just sit in their studio, listen to music, sip coffee, and make paintings. It’s such a good life! And I always have to go through hell. Nobody asked me to perform for 600 hours in a museum, don’t talk for three months. Nobody. I could just open the exhibition and go home and have a good time, but I just can’t!

SM: But at the same time, you told me earlier, you are looking forward to this experience.

MA: Totally! Because when I perform, I am 100 percent alive. My life is hell because I don’t have time to breathe. The less time I have in life, the more time I put into performance. The longer the performances, the more they turn into life itself.

SM: I heard some skeptics say, “Okay, it’s all about stamina, durability, pushing your limits, but what makes Marina Abramovic different from a stunt artist or a magician like David Blaine?”

MA: That’s a good question. I just met him recently. The difference is in the context. If you make the bread in the bakery, you’re still a baker, but if you make the same bread in a gallery, you’re Joseph Beuys. Context makes the difference but it’s not only that. I’m very interested in David Blaine, because he is not just a regular magician. He’s got enormous stamina and he’s really pushing his limits, which other magicians don’t do. So he is very close to that kind of aspect of performance, but there is always a trick and that’s what’s absent in performance. He was telling me about the piece he did in the ice cube. The ice was all around him, but there was a thin space in between. That was the trick; otherwise it wouldn’t be possible — he would die. He said that the most difficult thing was to stand there for five days and stay awake, because if he fell asleep then he would fall on the ice and that’s suicidal. He’s got a sense of adventure and danger, enormous stamina and willpower — but he is not working in the context of art, he’s working in the context of magic. Context makes the difference. I’m an artist; I work in the context of art.

SM: You showed me the altar in your bedroom, which is a collection of Orthodox, Buddhist and shamanistic objects. Your grandfather’s brother was the patriarch of the Serbian Orthodox Church and was canonized as a saint. Are you a practicing Orthodox? Do you consider yourself a religious person?

MA: No, I don’t like religions at all. Religion for me is very close to an institution and I don’t like what institutions stand for. I want to divide religion and spirituality. Religion I don’t like, spirituality—yes. When I was born, my parents were busy making their Communist careers, so I was raised by my grandmother until I was six. And my grandmother was deeply religious, I spent all the time in the Orthodox church. The priest was always in our house. I remember all those rituals with candles. I’m interested in everything to do with aestheticism, high spirituality experiences and ecstasy. In performance, when you push your limit to a certain point and overcome the pain, you reach a state of ecstasy, which is very similar to religious and spiritual ecstasy. All of those pure saints had that aspect. There’s a deprivation of food, the solitude, the silence, all the techniques I’m using. For the MoMA show, I stop talking for three months. I cut everything out of my life. No computers, no emails, no telephones. Everything is very minimal. When you cut off all that, then you really concentrate on yourself. Then your inner life becomes really alive. This is the way. When you purify yourself, you can create a charismatic space around you, which is invisible, but you can feel it, the public can feel it. The public is like a dog. They feel insecurity, they feel everything. When you’re there 100%. The only thing I’m concerned about is to be in that state. The moment I’m in that state, everything’s going to be fine. To reach that state is the most important goal for me.

SM: You devote a lot of your time to mentoring young artists and curating shows and festivals like the one you did in Manchester last year. How important is it for you to work with young artists?

MA: It’s very important, extremely important to have the contact with the young generation because they give you a sense of time and you can give them experience. It’s a kind of fair exchange. My generation of artists is being so ungenerous, so overly protective and jealous, thinking if you do something for young artists, they’ll take your place. But it’s so wrong, because there’s always a place for good art. In my time nobody ever helped me, but I was always saying to myself, “I don’t want to be that way. When I come to a certain age and experience in my life I can really open that and be very effective and show things to my students.” I always tell them, “Don’t let yourselves be exploited.” When you’re a young artist, you do so many mistakes. When I had my first show in Italy, the gallerist sold the entire show and I never saw a penny. I came with the second-class ticket from Belgrade. He didn’t even pay for my train ticket! He lied to me. He came up with all kinds of excuses . . . One of my students was making a show, a very good one, and her gallerist demanded five major works from her, otherwise she wouldn’t give her the show. The artist girl came to me and asked what to do. I said, “Just tell her I’m not giving you any work.” She told her that and she left. Then she starts crying, “You see, this was the gallery, this was my opportunity.” I say, “Wait!” After one week the gallerist calls back, “What about three works?” The girl calls me to ask my advice and I tell her, “Say no.” Then in the end they produced the show, the real thing, and the gallerist asked the girl, “Who have you been consulting?”

SM: I think every artist knows how ugly the art world can get sometimes.

MA: And then you have to learn the hard way how the bloody market works and how ugly this world is! Because that’s what they do — they really try to take advantage of inexperienced young artists. And I feel like that’s the kind of protection I can give them. I also love to be in the position of a curator and show the work of the people I really believe in — great artists who don’t have any galleries or sales, but once you put them in the right context, many other people can see how great they are.

SM: Now you can finally enjoy the financial success. How important is the market aspect of what you do?

MA: You know, I didn’t buy this loft from selling art. [Laughs] I bought it from selling my house in Amsterdam. Only in the last 10 years I started making some money. Like John Cage — he was 60 when he started getting some money for his concerts. When I started doing performances, the idea that I could get paid for that was unthinkable. Who would pay for this? I mean, come on, nobody! I was living in the car literally from nothing, having an empty water bottle and asking for gasoline. Then started teaching, doing many different jobs, working as a postman, working in hotels and restaurants. I’ve done everything. Only in the past 10 years people stopped asking me, “Is this really art what you’re doing?” and I started selling my work . . . The only person who really figured out how to sell performances is Tino Sehgal. He studied economy and dance and somehow he put the two together and figured out what I could never figure out, that I should whisper my concept in the ear of the curator, no photographs, and then sell it for 150,000 dollars, as he does. It never happened with me. I’m 64 now, and I’ve been doing this for 40 years, but I never made so much money with my performances. Thirty years ago for very little money in credit I bought a house in Amsterdam; it took me twenty-five years to restore it, and I sold it for a lot of money just nine years ago. That’s how I got to New York — not because of my work, but because of the real estate, in a kind of Slavic way . . .

SM: Well, the point is the result that matters, not how you got there!

MA: And that’s why I always tell young artists, “You have to get paid for your work.” If you just ask the plumber to come and fix your water pipe, he gets paid more than any performance artist. This is one thing I learnt. I did too many things for free. For Seven Easy Pieces I didn’t get paid a penny and it was such a hard work! Absolutely zero! I did everything by myself. They were always saying, “We don’t have the money.” They were afraid to do these things. And in the end, I was thinking, if I wait too long I couldn’t do it physically because I get too old. So I’ve done it anyway.

SM: As much as you don’t like institutions, you are largely responsible for making performance an institutionalized art form. Now it’s hard to imagine that until recently it wasn’t considered as such.

MA: It was nobody’s land. This is why I don’t see the MoMA retrospective as just my own, but as a show that puts performance into the mainstream art. And all these young performers finally have the space.

SM: Tell me about the performance art center that you want to open upstate.

MA: It’s in Hudson, just two hours from the city. We got this incredible building, an old theater from the thirties that can fit 1,500 people. Now we have to find the money and we are going to find the money. So this is my next thing. It’s going to be called the Marina Abramovic Institute. I don’t want to be a director or run this place. And why do I want to have my name on it? Not because of egoism, but because my name became the brand for performance art. Look, it’s beautiful, it’s huge! This institute will only show long durational work. We are going to show film, video, performance, dance, anything — but it has to be at least six hours long. If it’s less than six hours, I’m not interested. I also want to have the school for the public, the public drill. To teach the public how they should look at long durational work. What is the system, what is the way? They have to learn.