Jimi Dams

Slava Mogutin

Introduction for artist portfolio in Eyemazing Magazine, Winter 2013

For over a decade Slava Mogutin, a New York-based Russian artist and author, has been known for a photographic body of work that ranges from highly stylized, iconographic images to portraits that blend the boldness and honesty of police mug shots with the fantasy and desire of vintage pornography.

Before his career as a photographer, Mogutin, born in Siberia in 1974, was known for his poetry and short fiction. When he moved to Moscow, with the ambition to become a great Russian poet, he quickly gained a reputation as an enfant terrible for his outrageous poetry readings and performances.

In order to support himself Mogutin began working as a journalist for the first independent Russian publishers, newspapers and radio stations. His outspoken queer writings and activism gained him critical acclaim but also strong official condemnation, which, after being prosecuted for years, ultimately forced him to flee Russia.

By the age of 21 the artist was granted political asylum in the United States and moved to New York.

Mogutin was able to re-visit his native country after a regime change and in sharp contrast to the reason for his departure, was awarded the Andrei Belyi Prize for Literature, one of the most prestigious literary awards. In addition he was invited to be a part of the Moscow Biennial and he appeared on magazine covers and in prime-time talk shows. Not known to let time go to waste, Mogutin took advantage of his stay in Russia to take numerous photographs that were later featured in, what turned out to be his first photography book, Lost Boys.

After having seven books of his writings published and having worked as a professional journalist for over ten years, Mogutin had decided the time was right to explore another way to bring his ideas across. He started focusing on photography, which, unlike writing, doesn’t require translation.

While his early work was confrontational in its conception and presentation, he moved to a more unified and quieter imaging in later series.

Previously people tended to get easily lost by the subject of the artist's work. Provocative imagery seemed overpowering even though the artist produced bodies of work that were formally quite different yet linked by addressing different aspects of vision.

In each of his series, beginning with his earliest work, Mogutin has explored the formal and cultural conventions of image making, drawing attention to problematic aspects encountered in the production of imagery and in the reading and response to it. The new body shows an interesting development into the formal aspect. The activity of looking is brought to the foreground as the common denominator. Mogutin wants to confuse and complicate the way the work is perceived and shift into larger questions that cover more territory.

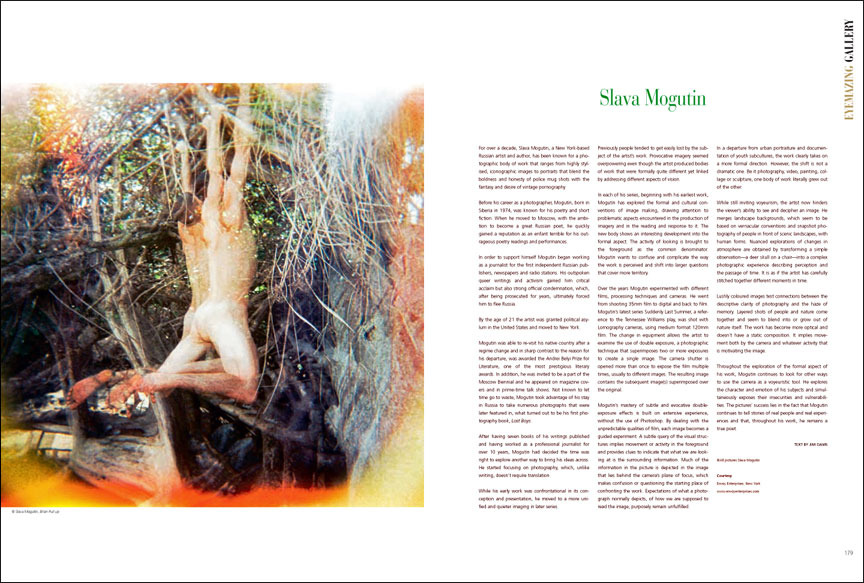

Over the years Mogutin experimented with different films, processing techniques and cameras. He went from shooting 35mm film to digital and back to film. Mogutin's latest series, Suddenly Last Summer, a reference to the Tennessee Williams play, was shot with Lomography cameras, using medium format 120mm film. The change in equipment allows the artist to examine the use of double exposure, a photographic technique that superimposes two or more exposures to create a single image. The camera shutter is opened more than once to expose the film multiple times, usually to different images. The resulting image contains the subsequent image(s) superimposed over the original. Mogutin's mastery of subtle and evocative double-exposure effects is build on extensive experience, without the use of Photoshop. By dealing with the unpredictable qualities of film, each image becomes a guided experiment. A subtle query of the visual structures implies movement or activity in the foreground and provides clues to indicate that what we are looking at is the surrounding information. Much of the information in the picture is depicted in the image that lies behind the camera's plane of focus, which makes confusion or questioning the starting place of confronting the work. Expectations of what a photograph normally depicts, of how we are supposed to read the image, purposely remain unfulfilled.

In a departure from urban portraiture and documentation of youth subcultures, the work clearly takes on a more formal direction. However, the shift is not a dramatic one. Be it photography, video, painting, collage or sculpture, one body of work literally grew out of the other.

While still inviting voyeurism, the artist now hinders the viewer's ability to see and decipher an image. He merges landscape backgrounds, which seem to be based on vernacular conventions and snapshot photography of people in front of scenic landscapes, with human forms. Nuanced explorations of changes in atmosphere are obtained by transforming a simple observation—a deer skull on a chair—into a complex photographic experience describing perception and the passage of time. It is as if the artist has carefully stitched together different moments in time.

Lushly colored images test connections between the descriptive clarity of photography and the haze of memory. Layered shots of people and nature come together and seem to blend into or grow out of nature itself. The work has become more optical and doesn't have a static composition. It implies movement both by the camera and whatever activity that is motivating the image.

Throughout the exploration of the formal aspect of his work, Mogutin continues to look for other ways to use the camera as a voyeuristic tool. He explores the character and emotion of his subjects and simultaneously exposes their insecurities and vulnerabilities. The pictures' success lies in the fact that Mogutin continues to tell stories of real people and real experiences and that, throughout his work, he remains a true poet.

© Jimi Dams, 2012