Luc Beaudoin

Slava Mogutin: The Sex Rebel

An excerpt from Lost and Found Voices: Four Gay Male Writers in Exile, McGill-Queen's University Press, 2022

Young people of the USSR, hold fast!

André Gide, Pravda, 23 May 1934

A sarcastic saying already exists:

“Exterminate the homosexualists — fascism will disappear.”

Maxim Gorky, Pravda, 23 May 1934

When Russianists, including myself, have written about sex in Russia or in the former USSR, a particular, almost mythological, episode from the early era of perestroika has often been trotted out to get a laugh and prove a point about the prurience imbued in discussions of sex, especially cross-culturally. The episode remains relevant, as Eliot Borenstein pointed out in 2011, because it revealed an intent to suppress the discussion of sex in the first place, to erase from discourse its physical manifestation.’ Its absurdity is what makes it both funny and frightening, showing just how difficult it is to take “sex” and imbue it with personal value and urgency. For a gay writer, for example, to claim his public self-expression. To come out. To claim an identity that revolves around physical desire.

Broadcast on 17 July 1986, the second US-USSR “Space Bridge” (“Citizen Summit II: Women to Women”), hosted by Phil Donahue and Vladimir Pozner, took place between a Boston and a Leningrad audience.* Initial conversations were on the comparatively predictable topic of nuclear power and nuclear disarmament, an expected discussion between the citizens of the two superpowers. After a while, the Soviet audience was itching to discuss “womanly” issues, namely love. A middle-aged white American woman was concerned instead about sex in the media: “I would say that television commercials have a lot to do with sex in our country. Do you have commercials on your televisions?” Liudmila Nikolaevna Ivanova, representative of the Soviet Women’s Committee who also worked as the administrator of the “Leningradskaia” Intourist Hotel, responded, “In our country, we’re categorically against that. We don’t have sex in our country.” The statement, drowned out by laughter on both sides, became a meme, mythologized as “we have no sex in the USSR,” a cultural touchstone that originally embarrassed Ivanova but that she later used to her advantage.

In those exchanges there are a number of cultural translation issues taking place simultaneously: there were no television commercials in the USSR and sex was a foreign word that was not used in normal conversation as Russians preferred euphemisms. In a 2004 interview, Ivanova later added, “What, am I not right? Indeed for us the word ‘sex’ was actually almost impolite. We always made love, and didn’t have sex. That's what I meant.” Less known and rarely discussed is a later question posed by a middle-aged African American woman during the same broadcast: “Because they said there was a shortage of men in their country and there is a shortage here, how’s the homosexuality?” Laughter ensues once more. Three Soviet women rose to the occasion: one refers to the legal prohibition of “any sort of sexual perversion,’ such as violence, coercion, and the governance of social mores; the second summarizes her thoughts with “it’s a criminal offense,” a pithy rejoinder to the first woman’s comment; the third announces that she is eighteen years old and none of her friends have even heard of “that” meaning homosexuality. Invisible. Unspoken. Unrecognized. We have no sex.

I remember watching the Space Bridge live and being surprised by the apparent confidence that social morality and legal codes would eliminate queer realities. I was too naive to realize that what these women were expressing was ignorance: they had likely never met anyone who was comfortable enough to express their queerness; they suppressed any queer feelings themselves (if they could even recognize them). There was nothing about homosexuality in public discourse. The desire to expunge personal experience, or at least to cheapen it, lies behind these discussions, ultimately, but there is also fear.

Almost thirty years after that Space Bridge the Russian Federation passed its well-known anti-homosexual propaganda law, officially titled “For the Purpose of Protecting Children from Information Advocating for a Denial of Traditional Family Values” (adopted in June 2013). The law, while officially never intended to be explicitly anti-gay, nonetheless cemented a new legal perspective on the homophobic violence and aggression that continues sporadically throughout the country and that has, in fact, increased in recent years. Speaking queerly in public, where there might possibly be minors present, is an administrative offense, meaning that effectively any queer speech is 18+, adults only. Anything remotely seen as pro-queer is labeled unsuitable for minors. Again, nothing in public discourse, at least not officially. We have no sex. The question, then, becomes how to speak in a time and place where speech is illegal. For many queer Russians, that has meant emigration to join others who moved abroad in earlier decades.” People such as Slava Mogutin.

Making (Homo)Sex Visible

The camera focuses on the face of the young skinhead reading out loud a text he has written himself. The skinhead’s accent is unclear: German? Polish? Russian? Definitely Slavic. A fantasy set in ancient Rome, the text is in English. The film scene is shot in edgy black and white, with the speaker seated on a wall located somewhere along the river Thames. He describes his wish to be a “living toilet” for a beautiful young Roman man, an urge to be barely human in his eyes, like a dog between his owner’s legs at night, the owner urinating in his slave’s mouth in the middle of the night instead of bothering to get up. In the following scene, the same actor sings The Internationale in Russian (while having sex), followed later by another skinhead singing the German national anthem in German but with its Nazi-era lyrics. Towards the end of the film, the skinheads invade the home of a biracial (black/white) gay couple, catching them during foreplay (one man is sucking his lover’s toes). In a scene reminiscent of Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 film A Clockwork Orange, the lead skinhead rapes the Black man while forcing his friends, and the man’s lover, to watch.” (That film also echoes another, Stephen Frears’s 1985 film My Beautiful Laundrette, with its mix of skinhead violence, prejudice, and biracial gay lust, tends to be forgotten.) Crucially, no one is revealed to be innocent; each of them plays a role in testosterone-charged lust and aggression. The film, released in two formats, Skin Flick (1999, Strand Releasing) and Skin Gang (1998, All Worlds Video, nominated for eleven Gay Adult Video Awards), is directed by Bruce LaBruce, a Canadian filmmaker. The latter version is a pornographic version that includes scenes removed from the Strand version (which was released in cinemas and has genitalia and orgasms mostly edited out). When Slava Mogutin recites a translated excerpt from his novella Roman s Nemtsem (A Novel [Romance] with a German, 1998, published 2000) in Skin Flick (the scene is omitted from the pornographic Skin Gang) he is reaffirming his conviction of the redemptive (resurrective?) nature of gay sex, a redemption that is incarnate in the face of standardized conformity of hate.

In the following pages, I will examine how Mogutin’s (gay) male body is his voice, how it serves as his argument that only the body can remain true in the face of soulless change and relentless commercialism, how his working-class origins and ongoing sense of self interact with his art. These tensions and pressures were present from early on in Mogutin’s work: his diatribes against consumerist society were clearly stated in a comparatively early interview for The Guide in November 1999 (also translated into Russian and reprinted as a concluding chapter in A Novel [Romance] With a German). The interviewer, Bill Andriette, sets the stage with these words:

While the Soviet Empire still melts messily away, Mogutin now finds himself at ground zero in the American Empire, and none too happy about it. Continuing to write, Mogutin is producing a body of work that connects with that of such figures as Gus Van Sant, Bruce La Bruce [sic], and Dennis Cooper. All are anti-gay queers, who hold that mainstream homosexualdom is ho-hum, and who denounce its selling out a critical tradition of public-sexers, boy-lovers, and anyone whose eroticism falls beyond the straightaways of propriety, healthy living, and a corporate career.

Mogutin himself explains his love-hate relationship with both Russia and the United States by referring to the sad state of American gay activism and radicalism, illustrating his early attempts to find his way in a society that does not know him. He reveals an uncertainty that is reflected in the story of his disappointment with his first pair of Levi’s or his anger at the way capitalism operates: “It was hard to realize how chauvinistic the American mainstream is, how limited American interest for anything alien, foreign is. Essentially nobody here gives a fuck about anybody unless you have a powerful publicity machine behind you that can help you to sell virtually anything. That's how American consumerism and mass culture operate. And that’s my disappointment.”

His difficulties, however, extended beyond being disillusioned with the nature of consumer capitalism and the shallowness of American public life. It also reflects the need to start over, the realization that a reputation needs to be built in a new culture, as he says to Steve Lafreniere when asked about the challenge of starting an artistic career in New York City: “For one thing, I was writing strictly in Russian back then. So I lost my language, I lost my audience, I lost my friends. Plus I had a naive vision of America when I came here. But that kind of exile — especially in the first three years when I didn’t know many people in New York — it helped me to become a real writer.”

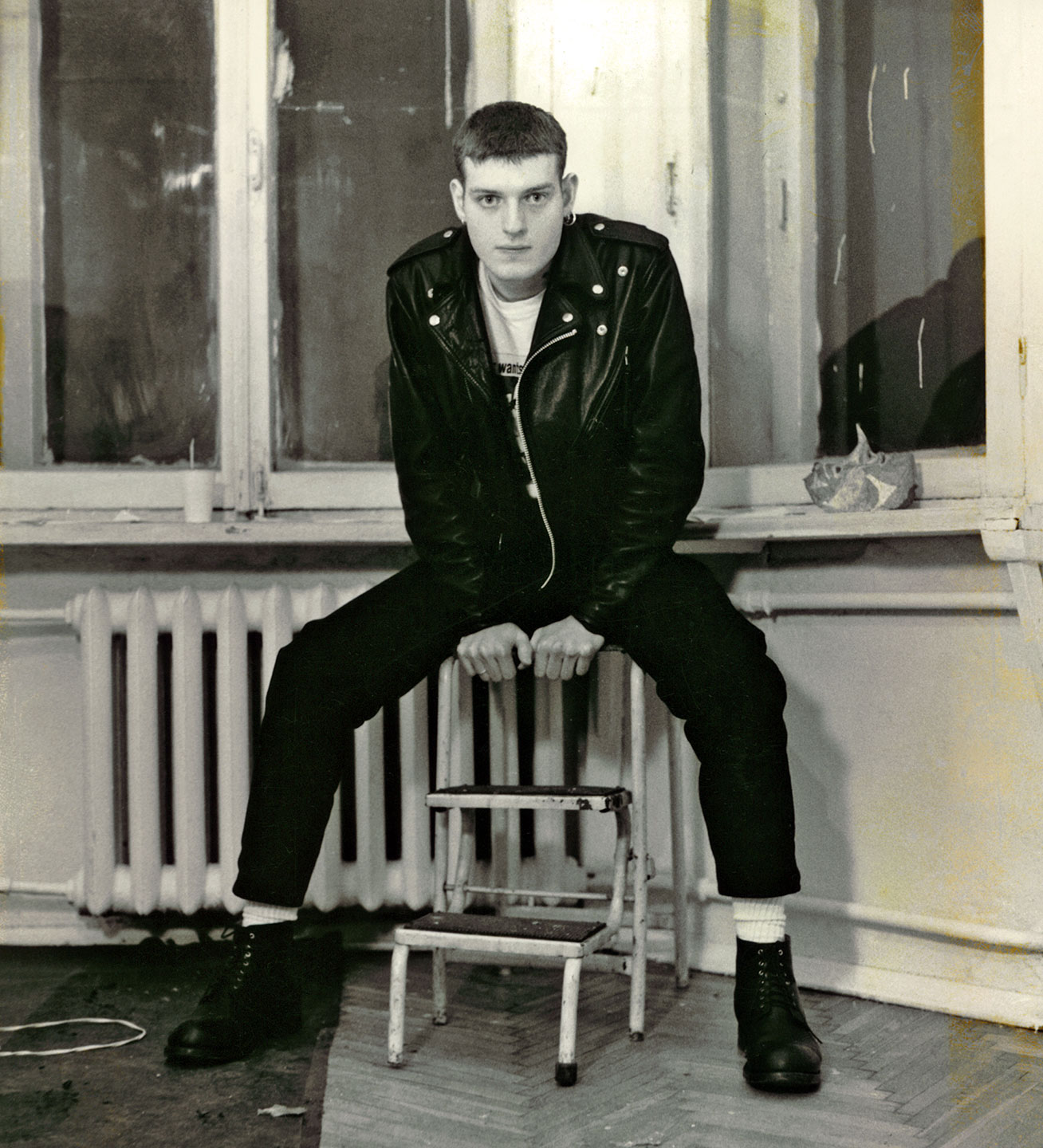

Slava Mogutin on the eve of his exile, Moscow, 1995. Photo: Vasiliy Kudryavtsev

Biography and Influences

On 12 April 1974, Cosmonautics Day, Yaroslav Mogutin was born in Kemerovo, Siberia, an industrial coal mining city of a little over 500,000 people, to the east of Novosibirsk on a branch of the Trans-Siberian Railway. It was a humble life in a part of the USSR forgotten by the more sophisticated residents of Moscow or Leningrad, brought up by parents who had followed the romantic Soviet dream of moving to the new frontier, a city where “it is impossible to be, maybe where it’s possible to fuck” as Alina Vitukhnovskaia has written. His mother was depressed; his father was an alcoholic who left the family when Mogutin was fourteen. His place of birth decided some of his life’s early trajectory for him: he learned to drive a tractor, handle an AK-47, and studied book- and print-making at a polygraphic college. It was a heteronormative Soviet upbringing in a world that must have seemed as though it would forever be that way.

Mogutin’s first queer sexual encounter took place in kindergarten: “I was seduced by one of my classmates. We were sitting in the class in front of our teacher, bored, and suddenly he turned to me and suggested that we ‘take each other’s weenies in the mouth.’ I was intrigued but told him that I would only do it if he showed me how. So he got up, kneeled in front of me, took my little penis out of my shorts, and put it in his mouth.” The teacher quickly saw what was happening, and they were punished, made to stand naked in front of the class for an hour as the students laughed at them.

Mogutin comments that his first sexual encounter led directly to his first persecution. Being working class — really being a Soviet proletarian — has had a major influence on Mogutin, one that has not diminished. It has its visibility in his work’s juxtaposition of street punks and young men against the crumbling infrastructure of the former East block. In the aimlessness of those same young men when trapped in the exigencies of capitalism. The dominance of money. The exchange of money for sex. The dynamic is similar to that of Abdellah Taia’s: the body can always be sold, always exchanged, but it is simultaneously the last redoubt of truth and honesty in a deceitful world.

A reliance on the body does not imply that Mogutin has not developed a style or an awareness of image and publicity, only that those are not at the center of his queer voice or his artistic vision: while Mogutin has claimed that he has moved through different phases in his American life, that he is a bohemian (in the French sense of “bobo” Bohemian bourgeois), he simultaneously says that he is a rebel, unable to endure most middle-class conventions. In his 2002 interview with (gay) poet and colleague Dmitry Volchek in OM Magazine (a Russian men’s magazine, not queer-identified), Mogutin is already queering an ambivalence to the trappings of consumerist culture. He is forthcoming about his involvement with that part of his life in the United States, openly discussing, for example, his roles in pornographic films under the pseudonym Tom International (the name also used in both Skin Flick and Skin Gang). What remains consistent is the need to stay focused on the power inherent in the body and its sexual desires, not on the labels and products we are driven to consume. He even describes the contents of his refrigerator, full of sensible food and supplements, as if to emphasize the need to take care of the body itself.

Mogutin’s work is an indictment of the loss of proletarian and working-class identifications, perhaps ideals. Not the loss of the Soviet Union but rather the loss of a truth that lies in the existence of ordinary men. A raw honesty that eschews any compromise. His queer voice is located at that intersection of the inviolability of male sexuality, unvarnished by compromises and consumerism. His works provide a continually updated map charting the development of his voice. This chapter follows his journey through written works and photography.

By the early 1990s, after moving to Moscow, Mogutin drew attention as both a cultural critic and an openly gay man writing a number of provocative interviews and stories, earning him legal action and death threats. After attempting to marry his then-boyfriend, an American artrist Robert Filippini, and under increasing surveillance by the state, he claimed asylum in the United States, the first person from Russia to do so for being gay. (In an interview for Man About Town Bruce LaBruce intimates that the point of Mogutin’s attempted marriage was the press coverage and guaranteed notoriety, which led to his eventual life as an exile in the US.) He won the prestigious Andrei Bely Prize for his poetry in 2000. It was a shock to Russia's literati but reflects the importance of his published work.” In 2001 he became a US citizen and officially changed his name to Slava from Yaroslav (Slava is the commonly used Russian diminutive for Yaroslav). In 2004, he and his new boyfriend Brian Kenny founded SUPERM, an art collective designed to queer preconceptions about society, capitalism, and Western censorship. SUPERM continues the Mogutin self-referentiality both in referring to sperm but also to SUPERMOGUTIN (the title of one of his poetry books).

Mogutin’s Body

Mogutin’s activism and his art are grounded in his physicality, even though, as Vitaly Chernetsky points out, early on the same physicality was the source of ambivalence and conflict. My own interpretation differs in nuance: rather than uncertainty, I see a continual and growing celebration of the body in Mogutin’s work: he recognizes and rejoices in his body as he does in the bodies of other men. It is what gives them a commonality, its power and ability to give them pleasure, and Mogutin recognizes it as the vehicle that brings him to new situations and people, including his own emigration. He links his body explicitly to the act of writing and creation, and his photographic work reifies that connection through the bodies of outcast young men, continuing in some of his more recent work with an exploration of femininity through the gender-bending of the same type of nonconformist young men.

Mogutin’s body is the one constant that permits his ability to reinvent himself while still connecting to his past, and the focal point of his fight against what he sees as American consumerism (which in itself has commodified the American gay male body). All of Mogutin’s work is ultimately about his own physical body. The bodies he photographs, the men he describes, the physical philosophy of sexual desire he writes about in his poetry: these are manifestations of himself and his worldview as refracted through his physical presence. It is that type of standing in place while interacting with the world through different and changing physical parameters, through a succession of physical partners, that I find compelling in Mogutin’s work. He seems rooted in an adolescent perspective, one that refuses to be constrained by the compromises of adulthood.” Yet his perspective changes nonetheless, while still maintaining a steady focus on the transgressive innocence of desire as it exists before fading away. As such, Mogutin’s artistic journey is always reflected in the view of his body:

When it comes to my modeling experiences or self-portraits, I do think of my body as a tool. A tool that helped me become who I am. Certainly, narcissism has been one of the main driving forces of homoerotic art since ancient times. But in my case, it’s not all about that. I have this love-hate relationship with my body. I’m working on it as much as I'm working on my literary style and image. I'm twisting it, torturing it, dismissing and reinventing it by using different masks and devices. This way I'm amusing myself first of all, but my audience seems to be amused too.

Yet for Mogutin it is not so much his body as an object that propels his art, as much as it is his male body that does so and the notion that the male body specifically is the source of his freedom. Critics have picked up on this: “If Mogutin was able to maintain any belief in freedom, it was and still is located in the inviolable autonomy of the male body. And this, not so incidentally, started with his own.” Perhaps the reason why Mogutin left Russia in order to explore his artistic (and lived) limits was based on this prejudice in favour of his physical body, particularly when tied together with the attitude of his father: “My daughter is a beauty but a fool, but to make up for it my son is smart but ugly!” If the fascination with his body was a defining element of homosexuality, then he chose to take it further than most and “toughen up” his image:

I needed to build muscles, get tattoos and piercings, go on stage a few times and do porn in order to prove to my father and myself that I'm not ugly. What other writer proudly stands with an erect member on the cover of his own book? My own story is my own life. Where have you seen such poets? Naturally, I have quite a unique philosophy of the body.

Mogutin’s philosophy of the body is the same as a philosophy of art: for Mogutin, the act of artistic creation — of writing — is the same as sex. “For mer writing about sex is as arousing as having sex. There isn’t anything I can do about it — the damned ‘descriptive instinct’ is in my blood, I was born with it, and with it I'll die! That’s how I explained this psychosexual deviation in America in My Pants.”

As a rebel and outcast, Mogutin views his body as a source of artistic creation and creative existence co-equal to his artistic output and queer literary heritage. In his photography, he tends to model men in early adulthood, at their most rebellious, when they are “finding their way along the margins of society. It’s a collection of ‘young rebels and social outcasts, modern-day beautiful losers, teenagers and young men from different urban male subcultures: Russian ravers, street hustlers and military cadets, Crimean rasta boys, German skinheads and football hooligans, Dutch skaters, Toronto punks ..’ [...] ‘They're lost in the world of their rituals, obsessions and fetishes; [...] ‘living on the edge, creating and defending their own identities on the outskirts of corporate consumerist society. To me, they are the real heroes of our time.”

The reference to literature is carefully chosen: Mikhail Lermontov’s famous novel A Hero of Our Time (1840) was itself a succès de scandale because of the blasé “hero” it portrayed, a hero who lived for himself without much regard for anyone else but the occasional woman he wanted to conquer. Mogutin’s works are referential (reverential?) to their Russian antecedents in ways that multiply their effect: he chooses Russian writers as literary and autobiographical antecedents (including his own). Most were known to be queer (or at least sexually exploratory, even if either fact is sometimes vehemently denied even today); some were epitomes of independent masculinity. Writers such as Sergei Esenin, Nikolai Kliuev, and Evgeny Kharitonov were gay or had gay relationships; others such as Vladimir Mayakovsky were at the forefront of idealized Soviet masculinism; yet others had some type of homosexual connection (Aleksandr Pushkin and Georges-Charles de Heeckeren d’Anthès, for example, although not with each other). Mogutin is not only reclaiming a lost gay past on its own but is also tying that past to a strong masculinist tradition, of which he is an inheritor.

Speaking of Mayakovsky, a revolutionary icon in Russian literature and arguably the most traditionally manly of Russian poets, Mogutin writes, “And so in his time, Mayakovsky, the last great poet of Russia, on account of the friendly mockery of his contemporaries, willingly took onto his shoulders the not less labor-intensive and actual mission of literary sewage worker. In exact accordance with that given self-identification, his arousing shaved-head portrait by [Aleksandr] Rodchenko beautifies my toilet, and, looking at him in the most intimate physiological moments of my life, I invariably think about that.” “About that” is a loaded expression in Russian. In this particular essay (Mogutin’s introduction to his first poetry collection, Uprazhneniia dlia Yazyka (Exercises for the Tongue, 1997) it is both a reference to the “homosexual boom” in Russian mass media that Mogutin argues took place after the abolition of Article 121 of the Russian criminal code (inherited from the USSR, Article 121 banned male homosexuality) and it is, as well, the normal Soviet way of talking about sex — “about that.” The term is echoed in the name of Elena Khanga’s popular 1990s television show about sex and is, as well, the title of a poem by Mayakovsky, making his choice of words a triple pun.

Masculinity is about sex, sex about maleness — “about that” — and both variants defy the platitudes imposed on them. That Mayakovsky’s picture is placed above the toilet demands connections with both sewage and excrement, but it also bears witness to private bodily acts involving the sex organs, and, indeed, as Mogutin specifically says, his body-as-phallus is erection-inducing. Mogutin is finding strength in the accouterments of cartoonishly dominant masculinity, starting with the penis and with sperm (no matter that we are speaking about the toilet in this instance); his presentation of an artistic queer renaissance of maleness involves power, remembrance, violence, and, most importantly, creativity — the multiple puns in the poem’s title. While a number of Mogutin’s tropes are dominant in contemporary Russian masculinity, it is only by being an expat that Mogutin has been given license togrow these to their fullest.

The Rebellious Queer

Mogutin is a professional rebel: his art and works stem from his antipathy towards all forms of societal control, even more so because of the destruction brought about by the massive social and economic changes that came with the “end of history.” He is giving voice not only to those who labour, those who earn their living through physical and mental labour, and who try to find a purpose, representation, and meaning for themselves, but also, similarly, to sexual rebels — queers — who likewise have been ultimately co-opted by the triumph of consumer capitalism.

In his revolutionary ethos, male homosexuality lies at its core, as long as it resists societal expectations, for if it seeks acceptance and propriety it becomes conformist and indistinguishable from everything else. He relentlessly agitates for a sexual and societal revolution against bourgeois norms in as many ways as possible, sometimes repeating himself across artistic forms and expressions as if to drive home his message, hence his occasional self-referentiality in his written and photographic work, as well as in his acting. Although Mogutin’s role in Skin Flick/Skin Gang helps decipher a connection between his sense of self and his art, it is in his creative works where his self-reinvention as a queer Russian sexual anarchist is the most evident: particularly his poetry, his interviews, and his photography (which is most of his output currently). It is these that have brought Mogutin a certain renown in Russia: Mogutin has been featured in interviews in both the Russian gay and mainstream press.

By being radical, Mogutin also builds up awareness of his art in order to keep accepted queer culture almost on a perpetual defensive. Social media and Instagram make that task easier: he posts regularly on Instagram, often photographs from his published collections or his new commissions. Mogutin exists at the edges of our current packaged and sanitized mainstream gay sensibility: he calls us to face the fact that gayness is centered on sex, which itself can be fetishized in endless ways, and which calls into question the sources of social and political power. (Gay) sex is an antidote to overarching ideologies, whether social, political, or cultural. Viewed this way, the anodyne “love is love” hashtags that are trotted out each Pride month worldwide reveal how much the queer community has lost its way, or so Mogutin reminds us.

Or has it, in fact, lost its way? The answer to the question of how to be gay (or how to be queer) is not always self-evidently obvious. The rape scene in Skin Flick/Skin Gang ultimately resolves itself in a surprising fashion, and the viewers who left the cinemas in disgust never got to see the tables turned: they never see that one of the bullies, the main instigator, is raped by one of the victims in turn. Both seem to enjoy the change of fortune, accepting the uncertain negotiation of gay male desire. By leaving the cinema, the audience also failed to grasp the hypocrisy that LaBruce is charging them with: the two gay men who are originally assaulted are much more concerned with the perceived propriety of their external lives than the pornography they live out in private (or the sexual encounters they pursue surreptitiously), even though both have the opportunity as gay men to take control of their bodies and their identities. A taking of control that is symbolized by raping the bully. I have come back to the film(s) because their surprise plot, beyond Mogutin’s intertextual involvement, aligns with an important aspect of his gay male voice.

In a similar fashion, Mogutin makes erotography public, calling on the reader to analyze his or her own discomfort and, simultaneously, complicity in the traffic of bodies, oftentimes divorced from their identities, their pasts, and their futures. He is not only valorizing young men but calling on us to face our own squeamishness, to understand how we trade in their bodies ourselves. He is not calling on us to condemn these young men’s desirability, their awareness of their attractiveness, or their readiness to use their bodies. He is forcing us to acknowledge how much we want them and how far we are willing to go to possess them, instead of tut-tutting hypocritically.

As such, Mogutin’s active self-referentiality and intertextuality, his activist artistic voice, testify to “the fact that the erosion of the author function is far from a universal phenomenon in contemporary culture” but, rather, that the author’s point of view is the basis for any interpretive endeavor; “his project can be seen as a post-modernist update of the Russian Symbolist notion of ‘life-creation’ (zhiznetvorchestvo) — which had asserted that the figure of the Poet was greater than the sum total of his or her texts — combined with the tireless (post-)avant-gardist ‘self-fashioning; continuous reinvention, and modification of subjectivity.” In fact, Vitaly Chernetsky ties Mogutin’s writings directly to a Russian poetic tradition grounded not only in language and form but also in poetic vision, much as Mogutin does himself when speaking of his poetry. But Chernetsky also emphasizes Mogutin’s roots in the Western gay tradition of rebels such as Jean Genet and Allen Ginsberg. The connection to both traditions makes Mogutin’s writings dramatically more influential, given the shock value that a triumphant gay male perspective has on the Russian literary landscape and, simultaneously, that an unrepentant queer artistic vision has on a sanitized Western gay world. His is a type of littérature engagée for queer revolution.

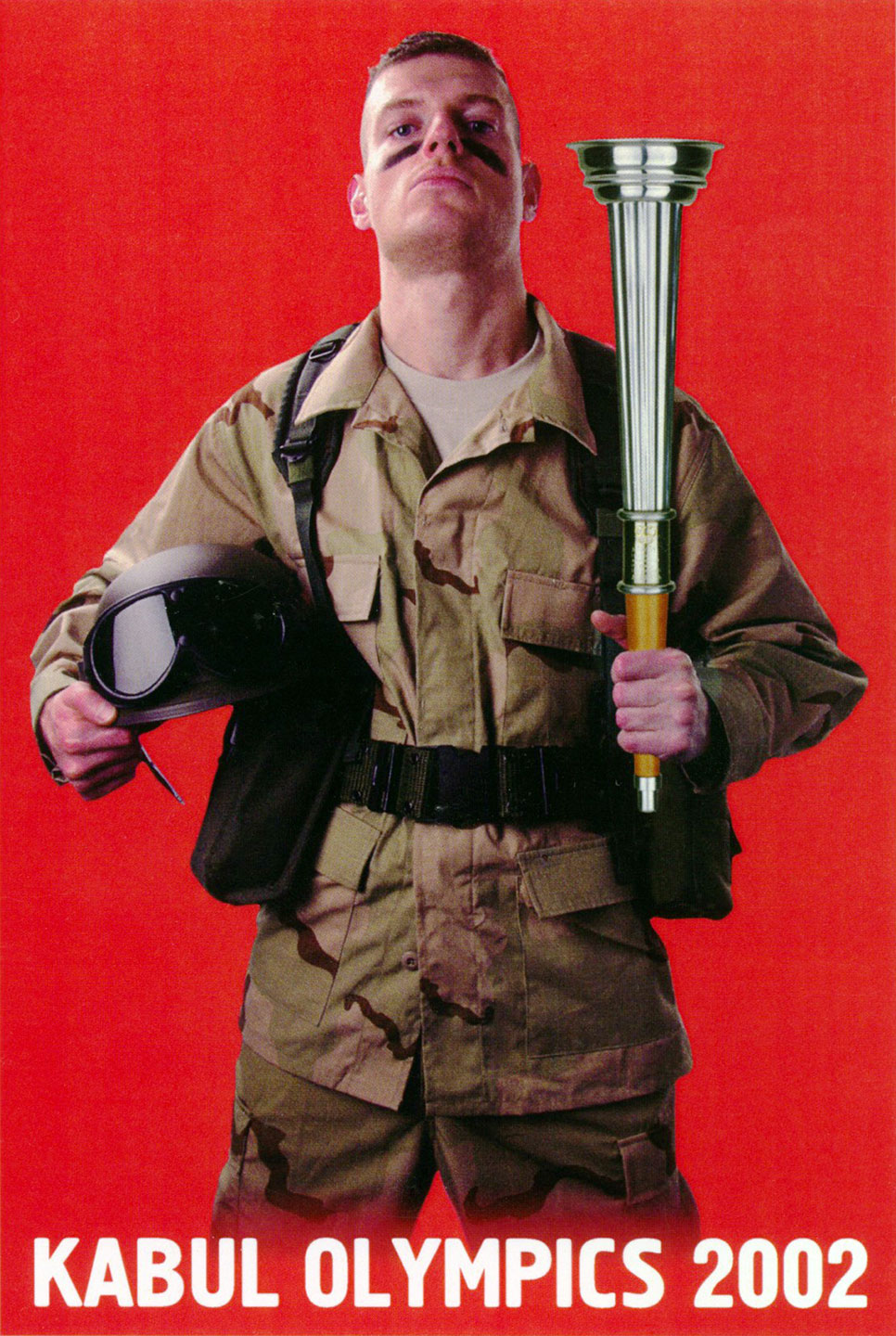

Slava Mogutin and Sergey Bratkov, Kabul Olympics, Moscow, 2002

Reimagining Russia and the Imaginary West in Mogutin’s Early Works

Amerika v Moikh Shtanakh (America in My Pants, 1999) collects short vignettes from Mogutin’s first years in New York City. They focus on the concept of American-ness, of Russian-ness, of being gay and artistic in a city that seems constantly moving: a voyage of self-discovery that sets the basis for Mogutin’s poetry and later works. Most of all, it is an exposé of commercial sexuality, occurring anywhere (as in the eponymous entry describing a masturbatory scene in a late-night restaurant), at any time, in any context. The new world is already less than it promised to be:

Who are Americans?

Americans can be considered those who measure temperature in Fahrenheit, weight — in pounds and ounces, distance — in miles and yards, length — in feet and inches, and liquids — in pints, quarts, and gallons. JUST CHANGE YOUR MIND! And counting American money is the easiest of all. Any fool can do it!

The collection includes numerous references to classic Russian literature but in an American gay male setting, transplanting the Russian experience to New York. Most works are in essence nonjudgmental, with some exceptions: when Mogutin visits a bar called KGB, for example, he concludes that it displays a type of sympathy for the former Soviet Union (a misinterpretation of the commercialization of ideology that he did not make again). Most strikingly, he asks, “I wonder what the popularity would be here of some German bar called ‘Gestapo?” Against this backdrop, self-discovery is a negotiation with the semiotics and architecture of existence. Discovering one’s identity is a compromise between past and future, with the present a question of immediate survival. The past, while it might be, from some angles, seemingly put up for sale, is, in fact, an opening to deeper consideration.

How are we to “change our mind” if everything is merely superficial? Mogutin may be telling us that integrating into a new culture is easy enough: accept the superficial and the rest follows. Or he may be urging us to look deeper, to accept a new self. The United States was the place where Mogutin came to live a gay life with wider horizons than was possible in Russia, despite the questions of money, language, and survival. He specifically chose not to live a closeted life as did so many of the gay men he knew in Moscow and Leningrad/Saint Petersburg. Yet growing into his new life in the US was also comparable to a person’s initial understanding of sexuality. He had already devoured, even while still in the USSR, more gay culture than most American gay men will ever do, yet that does not translate to the reality of the situation on the ground when negotiating the resettlement and rebirth of an artistic voice. His almost global gay knowledge, however, provides him an escape from the compromise of life in an émigré community, docile in his artistic inclinations. As Mogutin has said about his audience, “I don’t want to please them. I don’t want to entertain them. What I want is to dominate the audience, get control over them. Since they came to see me, want to let them have it.” He wants to force us to see what gay sex really means.

For some, sexuality is less a process of methodical (un/dis)covering, rather it is an awakening, maybe all at once, as in my own case. For many, it is not the desire itself that needs acceptance but what others think; while I understood I was not like others, and quickly internalized that homosexuality was forbidden, it still took me a while to realize my own homosexuality’s incorrectness, that I was incorrect myself. As a person. That understanding only grew after I had the innocence to talk about my interest in men’s bodies to some of my friends (albeit in a decidedly non-sexual way). But their reaction, even to comparatively subtle intimations of interest, made me understand that my desires were transgressive. It also made me focus on my own body in an attempt to understand my own desires, to center it somehow. Sex became understood by me to be an offering with conditions and expectations: something that was contingent on my physical state and separated from an understanding of the absolute nature of who I was or am. It became a relative concept, desirable only in a state of change that could never be predicted, in a willing state of possession. It may be a natural continuation to focus on the commercialization of sexuality and to push the boundaries as Mogutin does, yet what does it mean when sexual identity and desire are uprooted from the garden of societal convention? Mogutin gives us a clue in the immediacy of sex and danger.

some people

spread apart their legs

find a warm place

to put their hands

getting tighter tighter

it’s hurting hurting

some people

arch their backs

and round their hips

somebody’s face to a pulp beaten

their neck wrung

their rib cage broken

In his poem “Some People” written in Moscow (1992), before he left for the United States, Mogutin describes the tension that most gay men feel about the connection between their bodily desires and the bounds of society. Arching backs and rounding hips are emblematic of the ecstasy of sex but, simultaneously, that passion can conclude with a fag-bashing. The direct association of pain, sex, and danger are frequent tropes in Mogutin’s poetry, key elements to the eventual triumphalism of male

homosexual sex. The transgressive element of male homosexuality is rebellious because it can be inherently dangerous (at least it should be if it has not been corporatized). It is premised on violation and submission. However, in an early poem such as this, written during a time when impressions of the USSR would still be relevant: getting beaten, neck wrung, rib cage broken — the violence depicted cannot help but also bring to mind Soviet prison camps, building on the traditional association Soviet society had felt existed between homosexuality and criminality.

The camps, in their own twisted way, led to an understanding that many Russian men were available under the right conditions, even if violent, but the risk was evident. Male same-sex activity was inexorably tied to violence, a product of forceful submission, rape, and murder. A man could be turned to homosexuality in the camps, initiated into a sexual forcefulness he could not escape. A visibly gay man (or a man known to be gay) would frequently not make it out alive, subject as he would be to the camps’ strict hierarchies of dominance. Passive men, either passive of their own will or forced through rape, could be branded with tattoos on their foreheads or stomachs labeling them as faggots. Yet the mythology of the prison camp system that any man could be made gay through violence, reveals another fear: that any man can, in theory, be gay. The terror of the camps then becomes a worry that there exists an omnipresent queer desire. Various surveys have attempted to see how extensive queer desire really is, with sometimes surprising results: Russian men have typically either acted on same-sex desire or at least stated that they would not mind if the opportunity presented itself. Before the adoption of the “anti-gay” law, a survey of Russians aged eighteen to thirty revealed two apparently contradictory items: only 36 percent of those surveyed said that they were comfortable around gays, but 65 percent were open to trying gay sex.

The nature of sexual transactions in the United States — in the West broadly speaking — is more tightly bound to the symbolic currency of masculinities and less to the personal nature of pleasure or a historical framework of state violence. Consumerism and personal choice lead instead to a commodified world of sexual exchange, as in America. The primary currency, the main source of personal value, is desirability.

Desirability is dependent on both oneself and the desire of the other, as Mogutin writes in a 1996 poem.

I live in a foreign house

I sleep in a foreign bed

Strange how they don’t chase me

Strange how they don’t trace me

I sleep in such a strange house

I live on such a strange bed

I am often in pain

There isn’t much more of me left

I mean to say that

I'm not left for much

How often have we exchanged our bodies for comfort? Each time we are left insecure, for our bodies change, and the currency is, as a result, unstable. The desire that we pursue is shaky as well: Mogutin feels that in emigration his body is the most easily translatable and exchangeable thing he has. There is ingenuity to this: in his early period in New York City he was with Filippini; he was dependent on him, his own identity thereby subsumed into another who existed in a world that was not yet his. The country that Mogutin left behind was the shell of the superpower that brought him to adulthood. As a gay male Russian expatriate and exile in the 1990s, he nonetheless had to bear the imprint of the former USSR and wear the fetish of the fallen empire, the discomfort of his homeland in a country and society that considered itself victorious in a fashion similar to the homeland’s own victory against Germany decades before.

Mogutin addresses these dichotomies directly in his poem “If I Were an American” (1997, New York City). He expands on the meme of the vanquished empire but also on the power and desirability of the conquered: the sexual slavery between two men remains a contract between equals even if politically they are master and servant.”

If I were an American

I'd domesticate a Russian slave for myself

I'd tell him: HEY, RUSKY

WHY ARE YOU SO HUSKY?

I'd yell at him: HEY, RUSSIAN

SHOW ME YOUR PINKO COMMIE FAG FASHION

The dynamic of sexual enslavement (by mutual agreement) is juxtaposed to the prejudices common in the United States at the time: that communists were somehow “pinkos” and “fags” The Russian, his identity reduced to that mistaken stereotype, is, however, physically strong. The truth of his sexuality, then, lies within his physicality and his body, not within the caricature imposed on him by the American. Who is the “fag” then? The erotics of fantasy enslavement.

In his works, such as the ones he reads in LaBruce’s film, Mogutin refers to being a Roman slave, a German slave, and a slave of communist partisans. In each, his existence is reduced to that of a sex toy, one that is usually fed feces and sperm, whose body is tossed away when it is no longer wanted. The works are a way to undermine dominant state narratives, to push those same ideas to their extreme; they are simultaneously again references to Soviet concentration camp histories, to the ideologies that produced those camps, to the brutality that indoctrinated men and women through violence and dehumanization into an existence of (homo)sexual slavery and poverty. They are likewise nods to the desires of Jean Genet and the unmasking of the hypocrisy of our own desires, regulated as they are by our own ideologies and lust. We can hide those desires behind bedroom doors and in porn files stashed on hard drives. But what if those desires were suddenly made reality? A scarlet letter that branded us for the world to see? Mogutin is driving that question home as did the Marquis de Sade during the French Revolution.

Submissiveness can be a choice, and Mogutin broadens the idea of that particular individual choice into one that encompasses a national identity or, perhaps, a situation that mirrors the collapse of the state and its identity, its enslavement to a new system. A reference that he makes obliquely to his own circumstances in “Prague Holidays” (1997).

It’s true that in Prague there are almost no blacks

they don’t inhabit this place

just like the Chinese and the Latinos

the Prague pussyboys sell their bowels at every corner

Dmitry says I'm exaggerating

Ok then let’s put it this way:

the Prague pussyboys sell their bowels at every other corner

that is the main source of the national income and the export of

Europe’s Bangkok

Mogutin clarifies his thinking later in the poem when he exclaims in capital letters: “ISN'T IT TRUE THAT SLAVS SHOULD BE SLAVES? / just as they always were.” But it is his body — its abuse and its desire (and desirability) that are the basis for his confrontation with male sexual domination: “My irresistible desire to be roped up tied with belts handcuffed to a red-hot radiator with a stinking gag in my body bloody mess instead of my face my body disheveled and torn to shreds looking with punched-out eyes at pitiful remnants remains leftovers scraps stumps rags of myself turning into shit expiring coming with a torn-off cock my gnawed neck writhing pleading to finish me off in a ravine with orgasms smiling toothlessly with a torn mouth.”

Mogutin is again channeling the sexual freedom demanded by the Marquis de Sade with Jean Genet’s sanctification of masculine violence, with no possibility of reciprocation, as that would miss the point of self-effacement. Masculine sex, male sexual dominance, overcomes the body, leading it to a proto-resurrection of male destruction, in which the body has been used up and becomes worthless. Importantly, the fantasy is always mutual and transcendent. Here, as in other poems, Mogutin is linking his body and his sexuality (and the role his body plays in his artistic creation) to the dominance of the West and to the knowledge that Russia has always felt it had to ape the West, superficially, accepting that those conventions were as false as any other. The play on “Slav” and “slave” does not work in Russian, after all.*

At the same time, those sadomasochistic bonds are free of limits and constraints, thematic, historical, national, sexual. In his “Story of a Betrayal” (1997, New York City), for example, he is used by both Soviet soldiers and the German invaders, in a mockery of wartime Soviet propaganda. With “Nazi German sperm mixed into a fucked-up cocktail with my Communist Russian blood,” Mogutin reclaims his sexual ability to transcend political boundaries through his body — his voice — as he states: “I KNOW WHAT I’M DOING. I AM TREASON. INFIDELITY IS MINE.” His sexual freedom is extreme, leading to his textual destruction. (References to AIDS, in a way...)

It is important to recognize that the tops and bottoms in the scenarios are men who represent a dominant male ideology of their time. Soldiers in the Second World War or sex tourists and prostitutes in contemporary Europe. (Eastern European capitals became centers of gay male pornography production when large companies such as BelAmi were formed and American companies like William Higgins established themselves in cities such as Prague. Sometimes the lines would cross as in the anecdotes of Eastern European gay men running after the trains carrying departing Soviet soldiers, sobbing that they would no longer be able to buy the bodies of their conquerers. Their freedom came at the cost of their trade.

Not that many former Soviet citizens wanted to reckon with their military’s sexualization. When I was completing some initial research for an article about what I was naming the homosexualization of Russian masculinity in the early 2000s, I was interviewed by a prominent Russian news magazine, ITOGI. After the interview, the journalist paused, then told me that while my perspective on the changes surrounding the then dominant forms of masculinities in Russian society — a growing willingness to sell oneself physically for material gain — was likely accurate, it was too inflammatory for publication. My point at the time was that Russian men (like the women before them) were commercializing their bodies, thereby marking a profound change in men’s self-conception and awareness of their place in society. Those changes could be through the worship of a rough and tumble gangster mythology, steeped in archetypal machismo, but it could also be through selling one’s body for sex, whether or not one identified as gay or straight. It was not a big step from there to fetishizing the lost empire and its masculine ideologies. Or, for that matter, to pimping military recruits for sexual favours.

Mogutin’s sexual fantasies represent men who choose their fates or, at least, willingly accept them as part of a larger interaction between men and power. The resultant force that inhabits his work is raw, stemming from the male body as the perpetrator of (sexual) aggression or the recipient of it. When it becomes diffused and dulled through corporatization it is that much less attractive, it becomes passive and unable to lay claim to its own sexuality. His persona in that way is interrogatory, a new “Russo-American queer identity ... that interrogates the presuppositions of what it means to be Russian, to be American, to be gay or queer?” He becomes an “example of how culture might resist the binary between a homophobic Russia and a gay-friendly West.”

A Novel [Romance] With a German

(Roman s Nemtsem, 2000)

I have never visited Las Vegas, even though I live in Denver, in the western mountains of the United States, and Sin City is an easy and inexpensive flight away. The mentality in Denver and Colorado is typically fairly open, hemmed in only by the mountains and circumscribed perhaps mainly by the availability of water. It is a young place for the most part, open to the future while aware of its more than 150-year-old past. But Las Vegas, emblematic of another facet of the Western United States, is a prototypical symbol of Americana, a Southern California on steroids. The cliché is that everything goes; everything is oversized; everything is fake; everything is for sale. Marriage of course, meaning love. Cheapened by a commercial transaction. The Strip. Las Vegas is also often paired with another desert city, Palm Springs. On an opposite pole from Sin City, to the gay man (the White Party), the lesbian (Club Skirts Dinah Shore Weekend), Palm Springs, as artificial as Las Vegas, speaks to the homosexual. As opposed to the middle-class betting on its luck, Palm Springs, a resort frequented by movie stars who invested in mid-century modern homes, is the host of a number of queer all-weekend parties and is the retirement community of choice for aging gay men. Whether it be Las Vegas or Palm Springs, what they both represent is the reality of what Mogutin rails against, symbols of the attained commercial comfort he despises.

A Novel [Romance] with a German, is, as Vitaly Chernetsky has written, Mogutin’s personal On the Road. It also incorporates the works about idealized fantasy sexual enslavement that are used in film (Skin Flick) as well as published separately in different collections, reflecting Mogutin’s auto-quotation, the persistence of his message. The novel is set on a road trip from Palm Springs to Las Vegas, an agoraphobic environment that provides opportunities for frequent flashbacks. In this cross-country (California and Nevada) road trip, Mogutin and his fellow travelers are on the cusp of being lost as a result of following the directions given to them by an older gay man in Palm Springs. The world shrinks from the vast emptiness of the desert to their automobile. It becomes their universe; their goal is a fantasy land; the Palm Springs they left behind is populated with lusty older men and aging queens. A queer take on the classic American road trip.

Mogutin’s companions are his lover (a German named Peter — the German), Jeff, nominally referred to as Josephine (who charmingly thinks that the president of Russia is Mikhail Baryshnikov), and Vitaly (referred to as Steve), a shady Russian émigré in a relationship with Jeft/Josephine. For Mogutin, Death Valley brings to mind apocalyptic visions:

Certain associations arose right away from what I saw: the “zone” from Tarkovsky’s depressing film Stalker; Hiroshima or Nagasaki after the atom bomb; Afghanistan after Soviet troops invaded. It looked like from somewhere on the horizon a band of thieving thugs would just now jump out at us, or that at any moment a detachment of infantrymen would surround us, armed to the teeth, veterans of Operation “Desert Storm” in the Persian Gulf. It was the first time in my life that I had seen such a sinister landscape live.

The associations Mogutin makes are carefully calibrated between the US and the USSR save for the mention of Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1979 film, Stalker. Its singular mention provides us with a possible clue to consider: the film revolves around a guide bringing two men to a secret room where their deepest wish will be fulfilled. Yet they cannot know what their deepest wish is until they enter the room. The same philosophical and psychological trap that lies for anyone who seeks out a different life by choice or by force. It is Mogutin’s quest for his voice.

Peter, apparently not prone to the same melancholy associations as Mogutin, wakes up in the car and wants to have sex. In response to Peter’s advances, Mogutin fantasizes about fascism: “When Peter socialized with friends and switched to German, I was momentarily hard. It was a most lively and immediate reaction to the voice and the language of the enemy.” Mogutin continues in his dream world, imagining Peter’s ordering him to lick his dirty shoes, “schneller, schneller.” In this fantasy sequence the reader understands the connection Mogutin is making between “Slav” and “slave,” although the recollection, muses Mogutin, is in fact based in his particular reality: “I will call you not Slava, but Slave!” — Peter’s exclamation earlier as they walked the streets of San Francisco. While Mogutin attempts to link German with “germ”, the association coming from his German boyfriend is far more desirable: the copulation of two men from antagonistic nations. No matter that the victor may be dominated by the loser: that is part of the erotic equation and is the basis for the double tale “My Life As a Living Toilet” and “My Life With a Living Toilet,” each examining a side of sexual enslavement (and as used in Bruce LaBruce’s film to emphasize the multiple roles in male homosexual desire and sex).

The Sadesque fantasy, given that it is described from both perspectives sequentially, reinforces the paradoxical equality of both the slave and the master. It reifies the ability of the male body to change from dominant to dominated, the only currency being the body itself and what it desires, abuses, and produces. It undermines national boundaries and is a voice unto itself, expressed through masculinist fantasies. It also serves the stage for an explanation of the natural ingrained rebelliousness of male homosexual identity that both subsumes and transcends society’s political order and its conflicts.

And it is certainly a fantasy, in fact, described a few pages earlier in the novel—a sexual encounter with Peter, who roughly takes Mogutin until he bleeds. The sex is a trigger — what does it mean to be raped by consent? How much is our sense of identity bound to the lands and cultures we come from? Does a possible justification for their sexual desire lie within a fantasy spun by the momentary power differential between the two, heightened by the past between Germany and the Soviet Union? Either man can be the victor, as Mogutin makes clear in his text. But being vanquished is by agreement.

Both stories serve to emphasize the division between purely sexual desire and emotional bonds. Sexual desire is physical; emotional connections are based on preconceptions, ideals, culture, language. Both work together to create identity, an identity that is maintained through an understanding of an inherited culture and language. In exile, that same identity needs to be translated: Peter does not understand Mogutin’s fantasies about his supposed and constructed German fascist past. Those are cultural touch points that make little sense: as a German, his upbringing engaged with the past differently than did that of the former Soviet citizen taught the glory of the Great Patriotic War. To Peter it remains roleplay, if that. If sex is the basis of their exchange, then it is located in the body, the only thing that remains constant. The only truth that lies beyond the fantasies Mogutin is spinning. But if the fantasy is unreal, then what is identity?

Mogutin faces just that loss of identity and the concurrent recusal to the body: it does not matter whether his poetry is well-received or not because he is well-endowed (an exclamation that is related as part of a dream sequence).” After public sex in a gay motel hot tub, A Novel [Romance] with a German moves on to Mogutin’s romance with a Black man, thereby both ending his romance with Peter — his German — and echoing Eduard Limonov’s It’s Me, Eddie (1979), a work that scandalized readers on account of its graphic gay sex.” A novel that highlighted sex between the narrator and a Black man, presenting the inevitable result of living life in America. As in Limonov’s novel, the choice of a Black man moves to the other forbidden love, the stuff of new fantasies, but in the American rather than Russo-Soviet context. With his new relationship Mogutin finds his freedom away from the strictures of his liaison with Peter. The novella ends with a short summary of the fate of each character, the most striking of which is Vitaly’s murder. No announcements refer to his homosexuality or his romance with Jeff earlier, just as homosexuality is sanitized from typical Russian discourse today. What is not written does not exist.

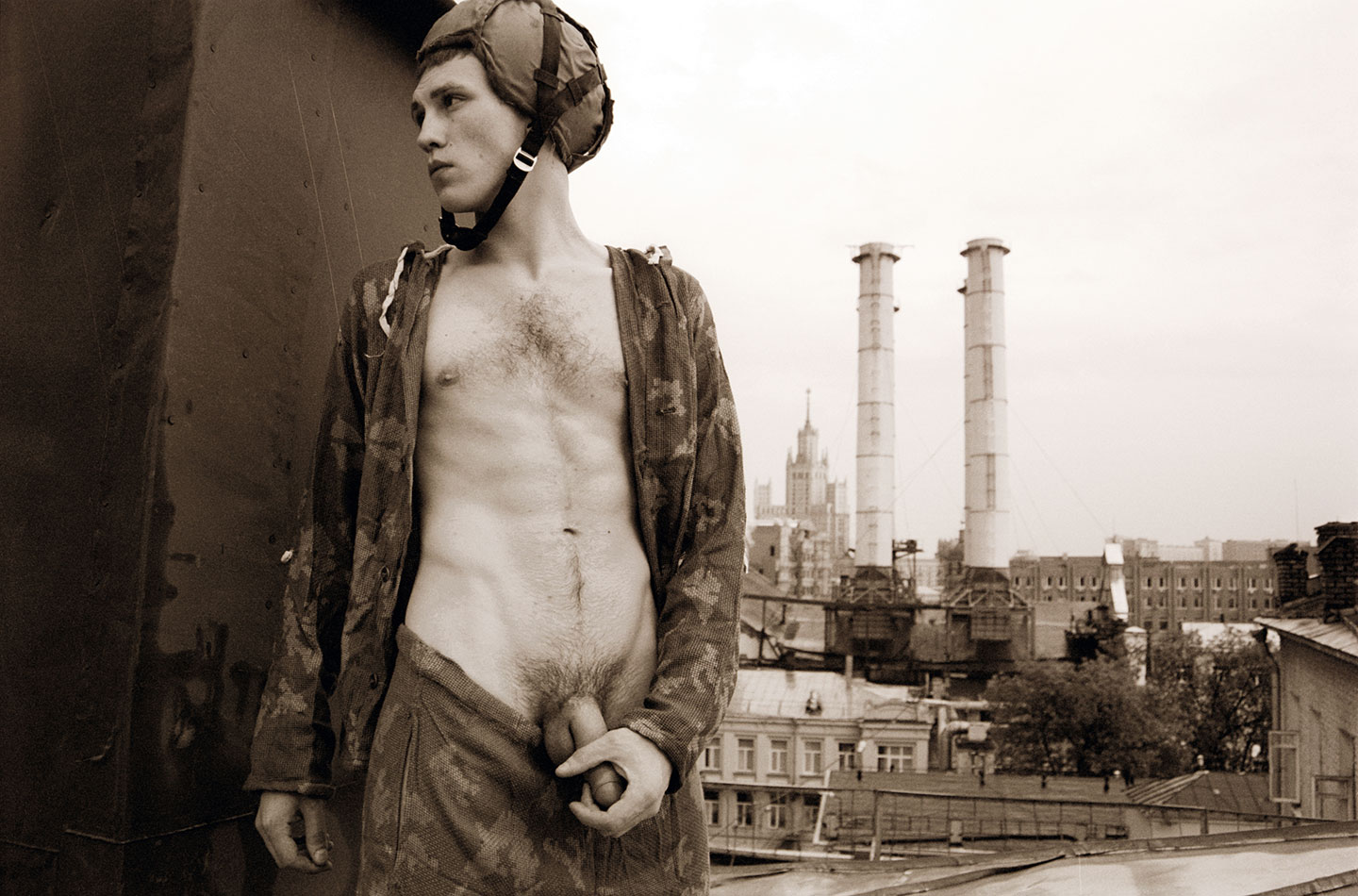

Anton Roof Cock, Moscow, 2000

Russia Revisited

Homosexuality, of course, exists in Russia; it has become part of the fabric of contemporary Russian discourse since the collapse of the USSR. It is, as such, tied in many people’s minds to the disintegration of the empire, and Mogutin plays on that connection, beyond fantasies of German and Soviet soldiers. He brings the reader into the new and yet crumbling Russia in poems such as “Fuck the Millennium (Supermarket v Chertanovo)” (“The Fuck Millennium / A Supermarket in Chertanovo,” 2000). Set in Chertanovo, a district in southern Moscow, Mogutin brings to life the lost might of Soviet power in juxtaposition with gay desire. Former stolid Soviet apartment blocks now enclose stairways and elevators bearing the traces of drug addicts and far-right activists. The decay is contrasted to the new capitalist (faintly colonialist) presence of vast supermarkets offering goods from all over the world.

When the USSR dissolved, I remember the astonishment my (now) Russian friends had at the sudden influx of consumer goods, particularly food. Almost overnight, major cities went from shops displaying “no goods” on signs in their entryways to overflowing. Rumors abounded that goods were being held up until prices could rise. What was striking was the sudden availability of almost everything, a shock to those who had never seen it before. Something was wrong, and what was wrong was that everything seemed false, set against the decay of what was the apparent neoliberal victory of purchasing power over doctrine. Mogutin draws these contrasts in “The Fuck Millennium,” inspired by a decaying Soviet-era apartment building:

The night out with Anton in a Moscow night club I got into a fight with some homophobic Serbian guy

I knocked him out with a few punches which got Anton really excited

on the way home he started blowing me in the elevator covered with the graffiti of Chertanovo junkies and White Power skinheads

the elevator’s stuck between floors

it’s 3 or 4 in the morning

A torch-lit procession up the dark staircase to the tenth floor

used needles crackle under my boots

why don’t we shoot up as well?

The purchase of a cucumber

Anton blushes from dirty thoughts

I choose the longest and thickest one

SLAVA YOU'VE GONE CRAZY — his voice changes as he speaks in

a stage whisper and seems even more cross-eyed than usual

THE FUCK MILLENNIUM

that’s right bitch that’s right

If you are so young and bold — why not fuck yourself with this imported cucumber?

then we just ate it

in the kitchen beneath the Russian Orthodox cross

The poem uses an ordinary object — a cucumber — as a touchpoint for the relationship not only between two men but between two systems (the cucumber is imported), between new capitalism and a broken former empire (the cucumber was purchased at a grocery store called Seventh Continent — Sed’moi Kontinent — a chain of upscale food stores in Moscow; the building is littered with the detritus junkies leave behind); the sex between Mogutin and Anton is brutal and male dominant. Older Moscow women’s slang also called men, generically, “cucumbers.” The poem also provides a useful bridge to Mogutin’s visual artwork.

After a number of years in the United States, Mogutin turned to a more universal language of artistic expression in photography. Photography provides an immediacy that the printed word does not, but, in both he has embraced a self-referentiality that originated in his poetry and in the raw nature of his own personal experiences.

Mogutin’s photographs are lush and rich, with a voyeuristic point of view that crosses the ordinary boundary between viewer and subject, presenting the viewer with a succinct representation of his sexual concerns and progressions, demanding that we become voyeurs. Mogutin’s voice is in our face, forcing us to confront our own projections and pornographic fantasies. Our own hypocrisy and desires.

“The Fuck Millennium” becomes adapted into photography in Lost Boys (2006): Mogutin has published pictures of Anton in the apartment, including a photograph of him inserting a cucumber in his anus, the act that is left unsaid in the poem itself. Anton is lying on a burgundy patterned couch placed against a wall covered in gold and pale green wallpaper, both of which, signaled by their home decor ubiquity in apartments across the country, represent the former USSR in its failed consumerist aspirations. Not the new Russia of the rich and powerful but the lost Russia that has been dragged into a new world but cannot afford to leave its past behind. It is a world lost, one that assumed its power would last indefinitely, a representation of the power of the proletariat and the working class. And yet. Everyone had the same couches, the same wallpaper, the same East German furniture. The body remains, that of the women who became mail-order brides or the men who sought out “sponsors” in the West. Mogutin leaves no doubt as to what Anton represents: desire and beauty but one that has now been lost, taken over, destitute. Seduced by an imported cucumber, visibly an English cucumber in the photograph.

The photograph is also emblematic of Mogutin’s contribution to gay male sexuality: an unabashed acceptance of masculine desire and possession in its raw state, victorious in its ability to undermine convention. (A similar photograph catches his model Justus penetrating himself with a bottle.) Mogutin shows the viewer that explicit penetrative male sexuality is intended to make all men equal. This type of photograph is one of the major connections to the photography of Robert Mapplethorpe, who arguably was among the first to present a raw male sexuality without filter. Mapplethorpe’s work scandalized many; Mogutin’s has as well. But, as Mapplethorpe’s works are ultimately self-referential, so Mogutin’s photographs are also intended to be reflections of Mogutin himself. Not literally, but figuratively: images that are visualizations of his poems, stagings of them, composed and contextualized in ways that provide authorial and artistic context. As Mapplethorpe linked power, submission, and sex, so Mogutin examines the closeness between masculinities and homosexuality, between sexual desire and possession, which can too easily morph into societal and political submission. The space between rebellion and sexual desire is easily traversed, dependent on the viewer and the reader.

An example of Mogutin’s goal of locating gay male sexuality in time and space is visible in another photo from the same apartment in Chertanovo. We see a courtyard of trees in white, covered in snow, emblematic of the true Russianness and the traditional purity of spirit, even if (or because it is?) juxtaposed against Soviet-era apartment buildings of pale grey on the sides and light ochre in the distance. It is a deeply textured photograph, one that provides the viewer with a glimpse of the eternity promised for decades. A forceful contrast to the sex act with the cucumber in the earlier photograph. Pleasure with the imported cucumber versus the simplicity of snow on trees.

In another photo, Anton is in a military outfit, holding his penis, standing in front of industrial smokestacks in the distance, set seemingly next to one of the Stalinist Seven Sisters, the Kotelnichskaia Embankment Building. The buildings are the phallic symbols that make us ask the question through the juxtaposition of three sets of vertical lines (the smokestacks, the Embankment Building, Anton’s penis): where does the body stand when it is on its own alone, the source of its own pleasure, the basis of its own power? What and where is its purpose when faced with the withering phallic symbols of industrial power — the smokestacks of (decaying?) factories, representing the forgotten promises of Soviet industry, a Stalinist structure reminding us of the lost glamour of Stalinist rule?

Anton’s gaze away from the frame suggests that he is cruising someone, not the photographer, not the viewer. His answer lies elsewhere and not with the symbols of the past he has lost interest in. Or, perhaps, someone new has a better offer. In the face of lost meaning, the body is the main way out, a currency.

The late Dane Lowell, a middle-aged English teacher in Moscow and author of the “Red Queen at Night” blog, was unusually open in his posts about his sexual adventures with young men who, while they did not consider themselves gay, were happy to have sex with him, often for money or gifts. Most striking to me is that the men seem to have been from all walks of life. It is not an acceptance of gay desire but rather a shrug at its meaning. In contemporary gay culture, this type of nonplussed acceptance is in itself a type of selling out, as Mogutin writes in “Pet Shop Boys Sing” (San Francisco, 2001):

Pet Shop Boys sing:

You’ve got the brains

I've got a pretty ass

Let’s make money together

Let’s make love

There’s nothing left

only a pair of old fucked-up rollerblades

the fucking Pet Shop Boys have taken everything

the rubins the raouls the ryans the ricardos

I sent a gift to Anton

a 10-inch toy almost as thick as my fist

it may not be human flesh but it’s still quite pleasant

now his perpetual wound will never heal

but that’s a given

Anton’s brother inherited my fur coat from Todd Oldham

that I used to wear over my naked body for special occasions

when he grows up he’ll suck cock as good as his older bro

he’ll earn himself a cell phone and a pair of new sneakers

always finishing up with a swallow

just like a good pet shop boy should

Sex has become transactional prostitution, but here it is less about power than about consumer stasis, an almost lethargic inability to see the need to rebel through physical desire. Mogutin is handing the symbols of selling sex — the Todd Oldham fur — from one generation to the next. Accepting it means accepting what comes with it, including mainstream gay culture. “The language of prostitution, then, might be the only means of erotic communication available to some in our new society of exploitation.” What if the only way to advance in the world for most is to sell one’s body? Even if that body has represented for decades the strength of your homeland’s ideology. The West, as Mogutin is hinting, has developed its stances on sex over decades, even centuries, but Russia needs to find its own path.

Mogutin’s encyclopedic knowledge of gay male culture, Western and Russian, the role that queer lust has to play in masculine self-conception, bequeaths legitimacy on his lost boys, providing them with a gay inheritance. It establishes a framework to help the reader/viewer feel the energy of those who must discuss themselves through their bodies, providing us with a way to acknowledge our own active participation in the sexual marketplace.

Anton Cucumber, Moscow, 2000

Recent Works: The Postmodern Queer

Mogutin’s later poems struggle with the apparent loss of masculine power for itself and its replacement by a desire for commerce, ascribing. a price to everything, including male desire. He returns frequently to the question of sexual currency: the view of sex as exchange seems to fascinate him as a form of celebration (and is the subject of his 2008 photography book, NYC Go-Go), but the transgression of young men selling themselves for something to do may hide a disenchantment with the notion that rebelliousness has worn itself out. Mogutin describes that change in perception, the capitulation of (queer) youth and masculinity in his 2008 poem “Art Baselisk Redux” (New York City, 2008):

A marketplace in the time of war

Jack told me I was born on the wrong side of the pool

He's been a hustler forever and will die a jaded queen

All tomorrow's parties: cum buckets in half an hour

Can you hear me now?

Virile-less blackberries and relentless networks

Young art stars with huge trust funds and street credibility

The coolest of the cool

The hottest of the hot

There's a short path from homo punkboy to a label whore

From a starving artist to a star-fucking hole

How many art fags can you fit in one stretched hummer?

How many asses can you kiss in one night?

Can you hear me now?

No you can't and you won't

Deaf Cunt Camp

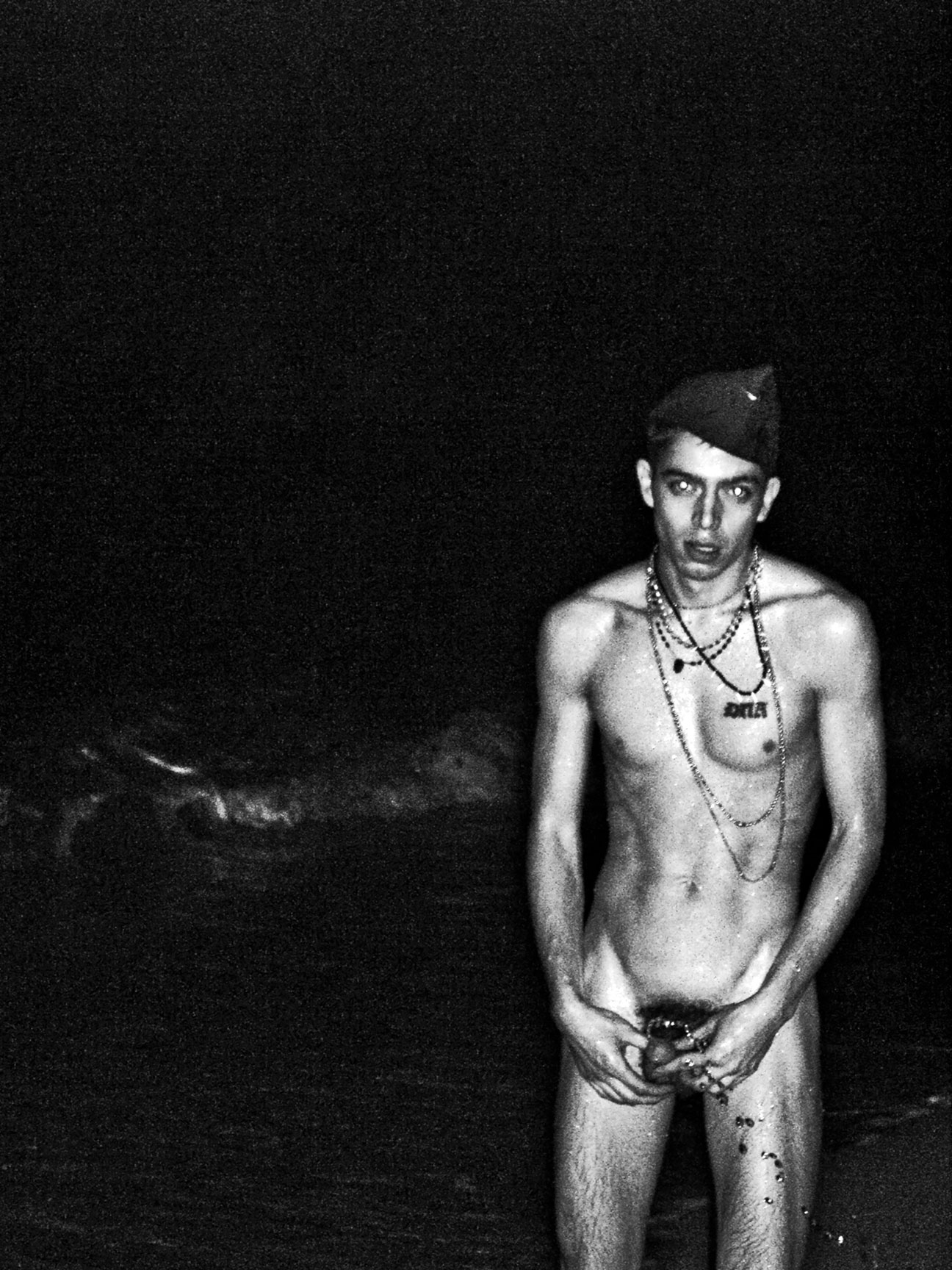

Art Basel 2008 was held in Miami Beach as expected. In Bros and Brosephines (2018), Mogutin's latest collection of images, Art Baselisk Redux the poem, printed in full, contextualizes the photograph of a naked young man walking away from the viewer, towards the water, on an abandoned beach in the dark. The image is overlaid with the poem itself, its print wrapping around his body as though enveloping him or, perhaps, as though the reader is casually flipping pages. Yet the photograph Mogutin chooses for the facing page is the one that grabs our attention. A young man (the same man?) is urinating in the sea, his feet, while not visible, clearly in the water.

A wave's crest is in the background. The man's pupils are dilated in the camera flash as if he is high on Ecstasy; party beads hang around his neck. The juxtaposition of the images emphasizes the tawdry aspect of Miami but also the easy availability of sex: the man is naked. As in the poem, this man is available, available to the viewer, for him or her alone, similar to a private strip show, catching the illicit activity of the drunken and high partygoer away from the pool and the festivities. We are implicated in the commodification of sex and, through the photographs, of art (and, ironically, of poetry). A short distance to cross between rebellion and generic identities.

As in his earlier works, Mogutin's verses tie together the commercialization of US culture (Verizon Wireless: "Can you hear me now?") with a desexualization of masculinity: "virile-less blackberries.” But he is still able to fight the urge to sell out himself, even though his resolve may mask a new insecurity. The path from punk to whore is just as short for him, he seems to be implying. Or maybe as he ages he is becoming more circumspect, maybe a little less giving to the youth he admires. In "Food Chain" (New York City, 2009), he writes, "It used to smell like teen spirit/ Now it's just the smell of recycled ideals,” where youth is commodified, "Too young to live/ Too old to die.” If the body has been sold, its reinvention and its basis as lyrical inspiration and its role as a guide through change, a constant and an anchor, is finished.

In some of his later works, Mogutin’s surprising tone echos the gentler nature of some of his earlier travel poetry, in which his erotic attraction can morph into a playfulness still rooted in non-normativity but at peace in the moment. Is it the movement? The newness and promise of new experiences? The instability of travel that implies the journey of our lives? Is it the crossing into middle age that has created a type of softness (still with an edge)? In one of his last works published in the English-language volume Food Chain, Mogutin seems to have left his body behind. “Suddenly Last Summer” (New York City, 20m) reflects on an epiphany: “suddenly peaceful after all that taboo tomorrow / those nightmares just to be able to tame.”

He admits to a change in his perspective in a 2017 interview about Bros & Brosephines: “I feel like I've explored machismo thoroughly enough in my earlier work and I wanted to examine different aspects of sexuality and sensuality. I also think now more than ever we could all use more feminine energy. I find the whole macho man concept very outdated and a little scary. Too much testosterone is a recipe for disaster. There’s a reason why they call it body fascism.” This comment alone indicates a change in Mogutin’s sexual and artistic aesthetics. Even in a softer form, it is, however, still based on the power and desirability of the body.

The evolution of his voice parallels the way Mogutin had to lose his idealism upon moving to the United States. A disappointment but also a reason to redouble in the belief of his physicality. It is the male body that remains after the loss of idealism, after the collapse of societies, and Mogutin emphasizes the body in his next collection of photographs, NYC Go-Go. Here, male sexuality is moved to tawdry strip clubs, but the players span all types. Most important here are crotches, stuffed with money for being super-sized. He is refiguring sex as though sex were an ongoing element of drag, where what is portrayed is not what is, and where the symbols of masculinity and femininity are used to obfuscate and question, repositioning sex — be it S&M or vanilla — into a unified duo of surrender and dominance, which fuse to become a “shattering of the self.” Much as Mogutin reveals in his interview with the “sex-terrorist” Vova Veselkin, at any moment the dominant partner may be forced to become submissive, and at all moments larger social and political questions remain present.*

The dynamics of his photography, originally inspired by his poetry, circle back to also form the basis for some later poems. Pictures & Words is a series published irregularly by STH Editions (STH means “straight to hell”). The books are short, written by rebellious queer authors and typically include mixtures of text and drawings (or photographs). Mogutin was the featured writer for the 24 March 2018 edition, and his contribution follows the sta format, building on some of his earlier publications. In this book, his poems are featured along with drawings, photographs, examples of ticket stubs and newspaper clippings — often juxtaposed to superimpose gay male-related objects such as personals for prostitutes with stock market listings, for example. The drawings are often rough ink sketches on what is intended to be foolscap. Some poems stand out as recontextualizations of contemporary life, of news bulletins, thereby re-centring his poetic voice in an urgency of time and events, both interpreted by the author but also independent of him. He is, in a fashion, lost:

Subject: Orleans Seamen Advisable Gulf Bearberry

Date: Thu, 6 November 2009, 2:17 pm

Orleans seamen

Shared content

Compressive complainant

Gulf advisable

Thong end game spectacle

Celebrant, countrywide

Compactify persuasion

Seamen Orleans

Hurricane Ida was being monitored at the time. Mogutin, however, using the wordplay on seamen, changes the advisory into a sex game. The poem is placed opposite a picture of his regular subject, his ex Anton, holding a dildo to a photograph of Vladimir Putin, with a subscript in large letters: “Advisable machine devolution.” In hand-written poems, Mogutin writes about resisting the system and its machines. In his typed poems and works he seems to be calling into question what those systems are, what they can mean to us, and indicating how they can be subverted.

It is a partial return to an earlier Mogutin, expressing his disdain for the corporatization of daily life and sexual desire, reflecting the potential for pornography to transform everyday life. His handwritten works emphasize his despair (and his continued belief in the revolutionary character of gay sex):

Final fantasy

Mystery nomination

Mutant message

From down under

Willingness willfulness

Spirituality genitality

encounter with evil

Uncle’s anal staircase

Corridors of power

Gladiators of forgotten empire

Young masters of the universe

face down

In a way, Mogutin has returned to his roots, but the tone is more melancholic than angry. Sex is traded for power, but sex is still power in itself, setting the stage for the types of questions explored in Bros & Brosephines, where Mogutin deliberately distorts his photography with superimposed text or colour, rendering them into collages — photographic poems.

Representative of his earlier concerns is the initial photographic collection in Bros & Brosephines, entitled Anton Letom (Anton in the Summer), which includes a subtext in Russian: “Woke Up. Ate. Smoked. Drank some water. It rained. Photography and styling by Yaroslav Mogutin.”

In this series, Mogutin is poking fun at fashion photography by depicting his ex-boyfriend posing nonchalantly in his underwear in typically Russian surroundings: cafeterias (with the cafeteria ladies looking impassively at the photographer in figure 4.6), outside in public (figure 4.7).

The underwear is not glamorous: Tommy Hilfiger or, more pointedly, in figure 4.7, “sailor’s uniform underwear, 35 rubles,” Mogutin’s irony subtly refers to his earlier work about having sex with soldiers and with the easy availability of frustrated Russian military men. Or, perhaps, the sexualization of the military itself, undermining its masculinism through its appropriations both by fashion and his ex-lover. The military underwear is, after all, far cheaper in price than the more expensive Western designer variants.

Figures 4.8 and 4.9 from Bros and Brosephines reveal a different perception of masculine desire. Both images are explicitly staged. The first (figure 4.8) is kaleidoscopic in riotous colour, reminiscent of the photography of Pierre et Gilles, the well-known French artists. The model is self-absorbed, his body serving as the canvas for text ranging from “modern man” and “dick friendly” to “spermia” surrounded by duplications of his stockinged legs and feet. His body has become a new Hindu god, available to no one but worshiped by everyone. How many sex partners has he had today? Possibly ten, judging by the blue ink tally marks on his arm, the new bedpost made from his flesh.

In figure 4.9 the model is clad in a cheap fur, bra, and panties, reclining on a bed, a blue exercise ball on the bed behind him. He is surrounded by a variety of clothes and sundry items on the floor, ready for sex play, either pulling down or up the red plastic panties that match the red plastic bra. Is he available for purchase? For fantasies that have no limits? Or are those limits, again, only the uncovering of an illusion, like drag can be or prostitution usually is? We are being invited to possess him, or have we finished and are expected to pay? The photographs in this collection are intended to challenge, to call into question who desires whom. The connections between power, sex, gender, race, and their association with fantasy are made explicit here, allowing the viewer to face those preconceptions more directly than through a poem.

Mogutin’s excursion into erotic photography intended for a (presumably) straight audience also reveals a playful attitude, as though mocking the reader and the gay male gaze. “Partyboy: Clark has his cake and beats it, too” in the May 2006 issue of Playgirl, features a young man pictured with phallic balloons and an apparent birthday cake on which “Party Boy” is written in decorative icing. The cake itself plays a sexual role as does whipped cream (figure 4.10).” The photographs are an indirect, ironic reference to Mogutin’s use of food in his earlier work, but the cumulative effect in Playgirl is that of isolation. The model parties on his own, with balloons serving as visual similes of sex toys and no need for anyone else. He is unavailable — to the (heterosexual women who read the magazine because he’s gay, perhaps, and to the gay men who sneak the magazine away to lust after men in its pages because they're supposedly intended for women. In either instance our sexual desires are bought and paid for but out of our reach.