A Queer (Re)claiming of Russian and Soviet Art

An Interview with Slava Mogutin

An excerpt from Queer(ing) Russian Art: Realism, Revolution, Performance

Edited by Brian James Baer and Yevgeniy Fiks, Academic Studies Press, 2023

Slava Mogutin is a New York-based Russian-American artist and author, exiled from Russia since 1995. Born in the industrial city of Kemerovo, Siberia, he moved to Moscow at age fourteen. There he started working as a reporter and editor for independent Russian newspapers, publishers, and radio stations, such as Echo of Moscow, The Moscow Times, The Moscow Guardian, Nezavisimaia Gazeta, Stolitsa, and Novy Vzgliad. He was considered one of the leading voices of post-Perestroika new journalism and the only openly gay personality in the Russian media. Forced to flee in 1995, Mogutin became the first Russian to be granted political asylum in the United States on the grounds of homophobic persecution.

Upon arrival in New York, Mogutin turned to photography and multimedia arts and since then his work has been exhibited internationally, including at MoMA PS1 and the Museum of Arts and Design in New York; Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco; Station Museum of Contemporary Art in Houston; Moscow Museum of Modern Art; KUMU Art Museum in Estonia; Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Castilla y León (MUSAC) in Spain; The Haifa Museum of Art in Israel, and Indianapolis Museum of Contemporary Art among others.

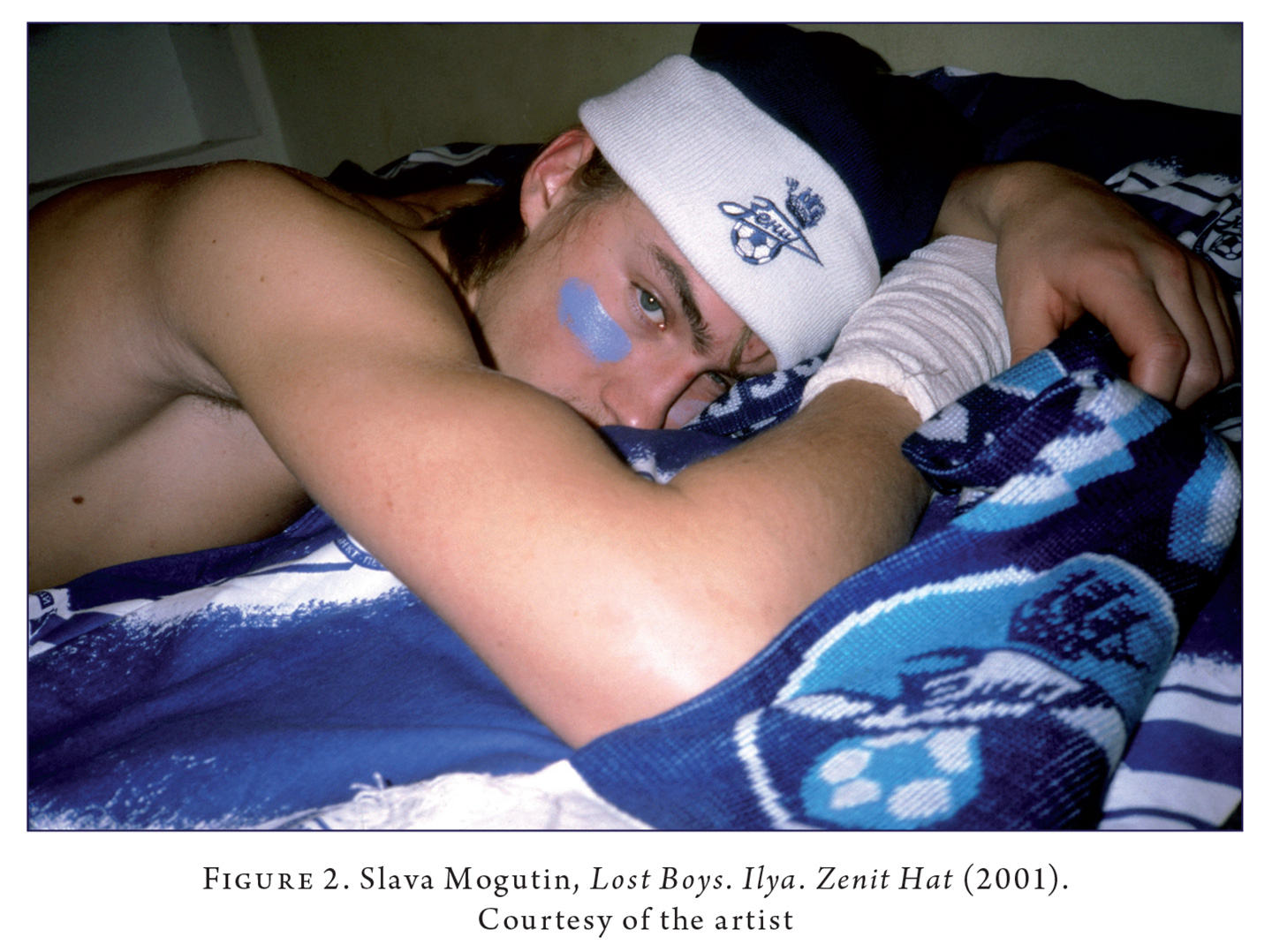

Mogutin is the author of two monographs of photography published in the U.S., Lost Boys (2006) and NYC Go-Go (2008), and seven books of writings in Russian. In 2000, he was awarded the Andrei Bely Prize, one of the most prestigious literary awards in Russia. In 2014, Mogutin released his first collection of writings in English, Food Chain (ITNA Press, Brooklyn). His latest photography monograph, Bros & Brosephines, was published in 2017 by powerHouse Books, followed by the illustrated Straight to Hell edition, Pictures & Words (2018).

Yevgeniy Fiks [YF]: Who are the queer figures in the history of Russian art that influenced you and are important to you? Whom from the Soviet and Russian art scene do you consider important from the standpoint of queer aesthetics or LGBTQ art?

Slava Mogutin [SM]: My three main inspirations are Aleksandr Rodchenko, both as a photographer and graphic artist, Aleksandr Deineka, and Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin.

I remember as a child going through a Soviet textbook and seeing Deineka’s painting Future Pilots (1938). At the time I thought of it as the most erotic work of art—that’s when I realized there was something. It looked like it could be somewhere in the South of the Soviet Union, maybe on the Volga River or in Crimea. I spent a lot of time there and would go swimming naked. I was around the same age as the kids in the painting, so it was one of the first moments when I realized I could be gay and was attracted to other guys. The painting to this day is very symbolic to me, and I find it interesting that the two younger boys are nude, and the older guy seems to be telling them something about airplanes. It’s a very tender, romantic image.

Aleksandr Deineka was primarily known for his heavy-duty, brutalist propaganda art, like The Defense of Sevastopol (1942), filled with very butch, hypermasculine characters. His mosaics of naked bathing men and hockey players (in Hockey Players, 1960) look so contemporary and homoerotic. It’s a fascinating combination of official Soviet propaganda and very subtle homoeroticism. The idea of male bonding and camaraderie was one of the key elements of the paramilitary education system we grew up under. That was the main function of art at the time. I remember at school we were taught how to reassemble Kalashnikovs. We were trained to clean our guns. [Laughs.]

Yet Deineka also had the most endearing, tender pictures of women who look like butch lesbians working at the factory, hanging their laundry and running through the woods. It’s an interesting depiction of gender segregation. From today’s perspective, most of Deineka’s work would be perceived as homoerotic. This is an interesting example of his late work from 1966, set in the South.

YF: It’s from the Khrushchev era.

SM: Yes, and Deineka made a name for himself as an official socialist realist artist. Male nudity seemed to be very restricted in the kind of work seen in subway stations and textbooks, yet you could get away with it if you had this type of official position in the art hierarchy. He was one of the most celebrated Soviet artists.

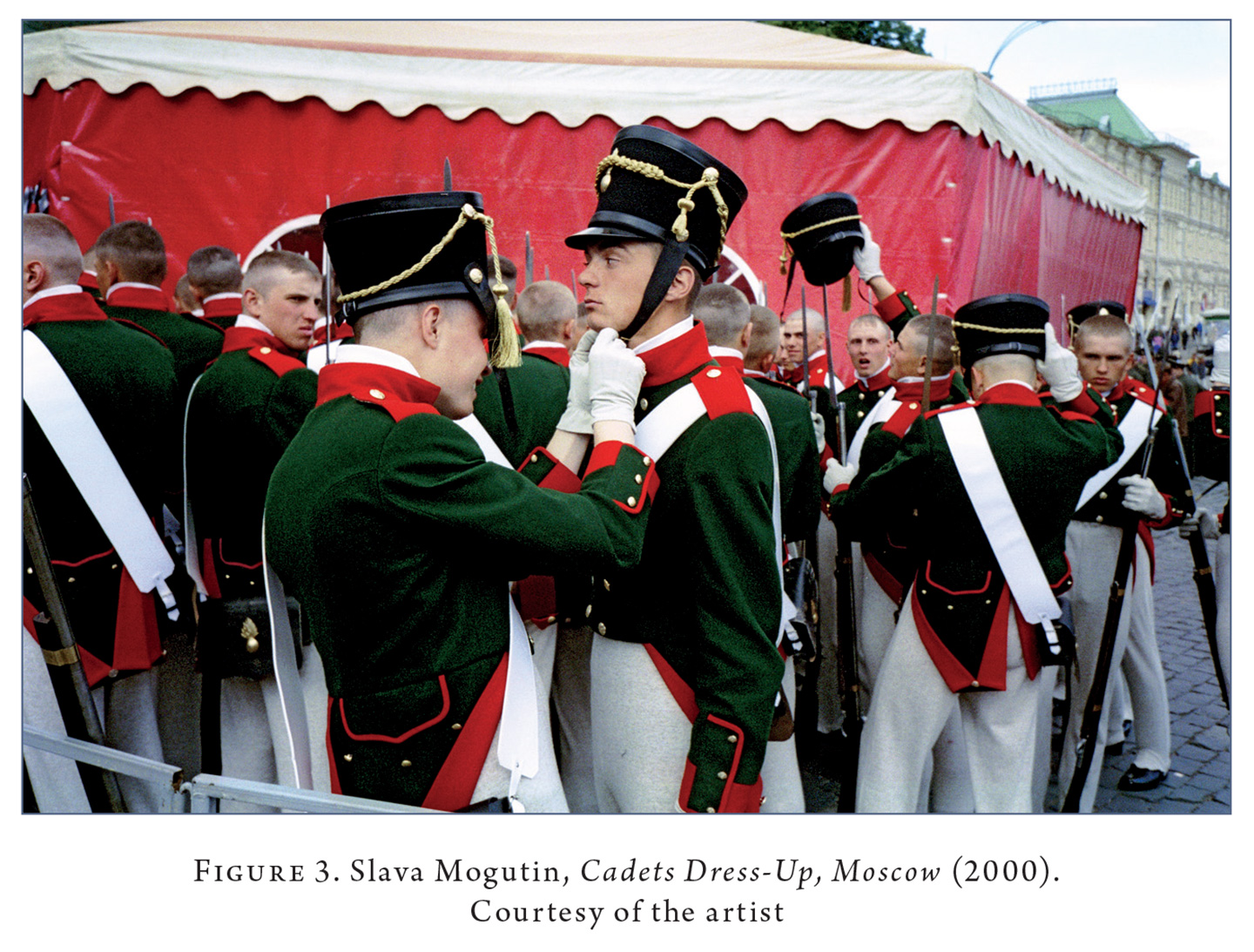

In general, I find socialist realist art very homoerotic—the same way as the Nazi propaganda was heavily based on the celebration of the young male body and physique. There was a similar movement in the Soviet Union at the time. You see Rodchenko’s documentation of the Soviet youth parading around in tight white underpants, marching in the Red Square and wearing next to nothing. It could be compared to Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia documenting the Nazi Olympics held in Berlin in the summer of 1936.

Now uniforms are back in fashion. Take, for example, Thom Browne who recently designed the whole collection based on Michael Jackson’s uniforms that were actually based on Soviet uniforms. It’s like a double interpretation.

YF: Were Michael Jackson’s uniforms based on Soviet uniforms?

SM: Absolutely. A few years ago, I had an outdoor public exhibition in Prague based on my book Lost Boys. My photos were displayed on billboards by Letna Park where the largest monument to Stalin used to be. Everyone hated it, it took six years to build. That monument was detonated right after Stalin’s death and the sculptor killed himself. But the plinth remained, and Michael Jackson had erected his statue that was on the cover of HIStory album on that plinth. They say history always repeats itself and it couldn’t be more symbolic than that. This happened during Jackson’s Eastern European tour when he was escaping from the child molestation charges. The aesthetic of the video and the whole stage design were very totalitarian and homoerotic at the same time.

Gosha Rubchinskiy is another example of someone who takes Soviet propaganda and blends it with the Russian Orthodox symbolism. And it’s wildly popular with the kids who think it’s the coolest thing right now.

This whole aesthetic was created by artists like Aleksandr Rodchenko. In retrospect, I think his work is very homoerotic. It’s made at the same time as the works of the first, pioneering American male nude photographer George Platt Lynes. Rodchenko’s propaganda posters and pictures of the military parades were a huge inspiration for my photography. I always try to imagine what Rodchenko’s work would look like if he were shooting in color. I often use similar extreme angles that became Rodchenko’s trademark style. I also find his collage experimentations very inspiring and post-modern.

Going back to Deineka and the three boys from Future Pilots, it became a recurring motif in my work. On a subconscious level, I was so visually focused on the things that I remember from my Soviet upbringing, things imprinted in my memory—even going back to classical Russian art. For example, the painting you probably remember from our textbooks of Peter the Great interrogating his son.

YF: By Nikolai Ge [Peter the Great Interrogating the Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich at Peterhof, 1871].

SM: I thought that was a very homoerotic picture. Then there was one of Ivan the Terrible holding his son that he had just killed painted by Ilya Repin (Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan on 16 November 1581, 1885). It’s interesting that there was so much going on in Russian classical art that could be perceived as homoerotic or queer. For instance, Aleksander Ivanov painted nude boys in Italy in 1830s. That was also one of the first erotic inspirations for me.

YF: We have one text on Ivanov in the book. Can you talk more about Rodchenko and Mayakovsky?

SM: As a poet I was very much inspired by Mayakovsky, and I was often compared to him. I find his flamboyant behavior very compelling, and I really think it was also gender-nonconforming and queer, in today’s terms. I was fascinated by his personal story of the love triangle between him, Lilya Brik, and Osip Brik. Mayakovsky was a total macho in his public life and really submissive in his private letters to Lilya Brik.

I was obsessed with the whole story. Lilya Brik lived to be very old, she was a living legend. She lived in Peredelkino, a vacation house for the Writers Union outside of Moscow, where I spent a lot of time with my father. I used to see her always surrounded by an entourage of people. This story and the rumors that Mayakovsky had syphilis created a cloud of very strange urban legends about him that I found interesting.

And I found the pictures that Rodchenko took of Mayakovsky to be strikingly beautiful and homoerotic. You see the trajectory of someone who started out with wearing a yellow shirt and painting his face to becoming something like the first skinhead. Starting out as a punk and ending up as a skinhead is how I see Mayakovsky.

The Russian avant-garde is rich with many examples and manifestations of queerness. Feminism was a big part of it, as well as sexual liberation and nonconformism. There was a popular movement called Down with Shame! The members of that group did social interventions, for example, they would ride public transit in the nude. Aleksandra Kollontai led the sexual revolution and advocated for free love as an integral part of Communism. It was part of the same revolution until they all broke down. Some joined the regime and others just vanished or escaped.

As a writer, I was also interested in Mikhail Kuzmin’s memoirs from that time and Vladislav Khodasevich’s memoir about the Silver Age (Necropolis), which describes a lot of queer activities. It was a truly fascinating period that I was obsessed with. I did not care much for Soviet art per se, but these were the figures that were my lifelong inspirations who inspired me both as a writer and visual artist.

I’ve always loved Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin’s classic paintings like Bathing of a Red Horse (1912), Red Horse, and Boys Playing, which were a homoerotic take on Henri Matisse from the same period. Later I discovered his other works from Central Asia. They were homoerotic and gender-bending—with very feminine boys that look like a third gender. That was also a revelation to me. It was all there, but it wasn’t presented as “queer.” These works were on display in the most important museums, but no one would interpret them that way. If they were created today, they would probably be perceived as “gay art.”

YF: Absolutely, yes.

SM: Pavel Tchelitchew was another contemporary who in many ways stylistically reminds me of Petrov-Vodkin. And if you look at the beautiful drawings of Rustam Khamdamov from the 1970s and 1980s, it’s a continuation of the same tradition.

YF: You’re looking at the works of these artists who are a part of the official art canon, yet no Russian official art historian would ever claim that there is queerness there and would probably deny any homoeroticism. Are we “reclaiming” these images and saying that they are part of the ‘Queer Russian Canon’? Or is it just a very personal thing to you, but they might not be queer to another queer artist?

SM: I’m coming from a very visceral perception of the work that I find inspiring. As far as claiming it and queering it, there is an untold story of that period that would be interesting to bring to light. We could reveal an interesting perspective on this art that was made a century ago simply because we learned more about our gender and sexuality in the last hundred years. Obviously, this would and should apply to our knowledge of the art from that era.

I feel that from an academic perspective, it’s really important to have this heritage established and revived. It’s already there but needs to be articulated and contextualized. There are many figures that would be considered queer in modern terms, who were active in both underground culture and the mainstream.

It is so interesting that they were artists and writers who were openly gay, and perhaps that’s the reason they were largely forgotten and sidelined.

YF: Even in the Soviet context?

SM: Yes, I believe so. Take someone like Mikhail Kuzmin, who died of natural causes in complete poverty and obscurity. He was openly gay, so he couldn’t publish most of his work and had a really meager existence under the Soviet regime. But he continued to write, even though he was officially banned.

YF: What about artists? Kuzmin’s partner Yury Yurkun was also an artist and a writer. But I’m not sure if his works are still around.

SM: I think Yurkun’s literary archive was published in recent years. I’m not familiar with his visual art.

My friend David Getsy, who wrote the intro for my book Bros & Brosephines, recently introduced this very interesting theory about abstract art as a way for the artists to express gender nonconformity in the times when it was impossible to be openly gay. It’s a great book (Abstract Bodies: Sixties Sculpture in the Expanded Field of Gender). Same goes for many Soviet artists who had to find different ways of expressing their queerness or gayness or gender nonconformity.

In the case of Deineka, even in his official propaganda paintings like The Defense of Sevastopol, if you look at all those half-naked hyper-masculine men, the devil is in the details, as they say. In retrospect, it appears to be very homoerotic.

Eisenstein is another example of having an official Soviet status and acclaim, but there were persistent rumors of him being gay. My friend Jean-Claude Marcade published a beautiful book of his erotic drawings, and most of them are overtly homoerotic in a very explicit way. They remind me of Cocteau’s drawings from the same era.

YF: Yes, but Eisenstein wasn’t very present in the Soviet visual landscape. There were a couple of his films that were shown, but his work wasn’t disseminated as widely as Deineka’s. Eisenstein was more of a classic —if not boring—his work wasn’t as available as Deineka’s was, which, as you say, was in children’s books. Eisenstein was different.

SM: Yet, in retrospect, knowing what we know about him now is worth noting. You could see his films on state TV, and they were studied in every film school. There were certain scenes that, in retrospect, could be viewed through a queer perspective since he was, in fact, a practicing gay man. But this part was never officially acknowledged, it was left to speculation.

Also, speaking of Pleshka, a big part of this oral history comes from people who knew someone from that era. Parajanov was persecuted for being gay and so was Vadim Kozin. My other friend Marc Almond recently produced a great BBC documentary about him, In Search of Vadim Kozin. It’s a very fascinating yet tragic story.

A big part of being largely underground involved these kinds of untold stories, speculations, rumors, and urban legends—even though most of them were fabricated. There were rumors even about the introduction of the first anti-gay law. There was one rumor that the son of Maxim Gorky was raped or corrupted by some evil homosexuals. So, Maxim Gorky became the first person who officially called for the criminal prosecution of gay people in the Soviet Union—and that was the reason for the introduction of the anti-gay law. I am now working on a book of journalism, Gay in the Gulag, with the title article about the history of gay persecution and homosexuality in the Soviet camps and prisons.

YF: You wrote it a long time ago, I remember it.

SM: Yes, it was extensive research originally published in the mainstream political weekly Novoe Vremya, the Russian version of Newsweek, in 1993. It was a huge undertaking that took many months of work. Later, an abbreviated version of that article appeared in the British magazine Index on Censorship.

YF: Let’s get back to Mayakovsky.

SM: Mayakovsky would be considered the first multimedia artist in modern terms—long before the term “multimedia” was coined. In his silent film The Lady and the Hooligan (1918) he plays a character who isn’t just an outcast, he’s a total punk. It’s a tragic story about unrequited love and he gets slaughtered in the end. It’s quite different from his official heroic image. There’s something in his personal story, with the love triangle that I find very queer. How would you explain that to Soviet schoolboys and girls? It was a known fact, but it was conveniently left in the dark. But why not look into it and read his letters from today’s different perspective? I don’t see anything wrong with that.

One of Mayakovsky’s famous slogans was “Down with your religion, down with your art, down with your social order, down with your love!” This “Down with your love!” can be interpreted as “Down with your bourgeois love!” or “Down with your heteronormative love!” He lived his life according to that slogan, and it was very important for me as a very radical artistic statement and political manifesto.

It’s ironic that the Russian futurists ended up the same way as their hero and role model Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, who was also very radical and nonconformist but ended up becoming a fascist. So, the Russian futurists eventually became allies of the Bolshevik regime. It’s a similar scenario. Marinetti was revered under Mussolini and was one of his spokespeople. A few years ago, there was a great show on avant-garde art at the Guggenheim with a very impressive selection of Marinetti works, including his recordings. It’s fair to say he was an evil genius.

For the same reason as Marinetti, people from the underground circles dismiss Mayakovsky as a collaborator with the Soviet regime. My generation rejected him as a phony. His poem about Lenin [Vladimir Ilyich Lenin] is just disgusting, the most awful example of propaganda. There’s no poetry left in his last writings—that’s why he killed himself. It’s either that or unrequited love or syphilis, or all the above. He’s a tragic figure despite his romantic and hyper-masculine image.